Four of us, Steve, Ed, Larry and I, signed up for a fishing trip. We were veterans of an ill-fated venture the year before, which began with a car accident in Minnesota and ended with us upside-down in a flooded plane in Neultin Lake, Manitoba, hundreds of miles from civilization. Despite our history, two newbies, Norb and Ted, joined us. A near-death experience like that couldn’t happen twice, we figured.

Soon after landing in Flin Flon, a small northern mining town which straddles the Saskatchewan-Manitoba border, we were in a float plane for a 30-minute flight to our destination. Hundreds of lakes glimmered below us as we soared eastward at 1,000 feet, and the splashdown went smoothly. The resort, Sickle Lake Wilderness Camp, had advertised itself as a haven for walleye, lake trout and northern pike, and for bear hunting as well.

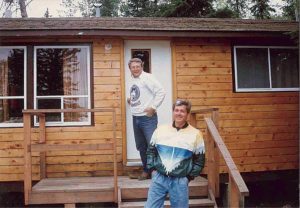

The “wilderness camp” was my kind of place. Adjacent two-bedroom cabins were cleaned by the staff daily. There was running water and plumbing. Home-cooked breakfast and dinner in a comfortable lodge. Buck Macgregor ran it, and his wife tended the bar.

On Monday, Buck met us at the dock with our guide. “This is Nick. He’s been with us for years.”

Nick looked like the real deal. Wiry, yet muscled. His face was eclipsed by the bill of his cap. I extended my hand, but he ignored the gesture, keeping his arms crossed over his large chest. “He doesn’t talk much,” Buck said, as Nick’s eyes remained fixed on the ground.

“We go now,” Nick said.

Ted was my boat partner. A good friend, he could be a man of few words, but was loquacious when it came to fishing. The northern pike, pre-historic looking torpedo-like creatures, were big and savage. On the first day, Ted pulled in a 10-pounder. As we inserted a jaw-spreader to remove the hook, there was a large, dead northern in his gullet.

There was a shore lunch every day. The other two boats from our group would pull up to a point and the guides would start a campfire, clean some walleyes or lake trout, peel potatoes and onions, and open a can of beans. Meanwhile, we’d relax and talk. The guides would try to extend the lunch, since it meant a break from running the boats.

That night, Ted and I were talking with Buck and his wife at the bar. “Nick sure is a great guide,” I said.

“I’ll tell you how great he is,” Buck said. “A couple of months back, he had two guys in his boat, and one of them had the brilliant idea that he’d stand up while he was fighting a northern. He was a heavy guy and he capsized the boat. Three of them ended up hanging on the edge. Nick swam the boat to shore. They could have died otherwise.” As he spoke, I had a flashback to our crash in the icy waters of Neultin Lake, and the despair of our almost hopeless prospects during that moment.

* * *

Something unusual happened on Tuesday. Instead of sticking to the main lake with the other boats, Nick motored us forward. There was no explanation. The 40-horsepower Mercury was wide open, and soon we were beyond sight of the lodge.

Finally, Nick geared down and steered us into a bay. “Fish here,” he ordered.

Ten minutes later, I felt a tug on my line. It had to be a big northern. He sounded, peeling the line from my reel. Then, just as quickly, his massive head breeched the surface. He thrashed desperately, trying to throw the Daredevle spoon that was lodged in his jaw. After an eternity, he gave up the fight and Nick scooped him up in the landing net. Twenty-five pounds! Nick held the trophy long enough for me to snap a couple of photos, then let it go, since our policy was “catch-and-release.”

I’d thought that Nick might say something. Perhaps a compliment on my handling of the catch, or at least a smile. Instead, he started the motor and moved us to another bay.

“Fish here,” he said.

* * *

Friday was getaway day. The Twin Otter had arrived to take us back to Flin Flon, and was tied up at the dock. The weather had changed, though. A cold wind was blowing, and there were whitecaps on the lake. Again, I flashed back to the stormy morning of our plane crash in Neultin Lake.

“No worries,” Buck said. “Not a major. We’ll get you to Flin Flon in time for your next flight.”

We made it on time, but Buck was wrong in saying that it wasn’t “a major.” The Maple Leaf Flag at the airport was flapping in the wind, which had increased since Sickle Lake.

There was a crowd at the gate for our flight. It was parents and 40 or more high school kids, on their way to a band competition in Winnipeg. When we loaded into the 737, the chatter from the kids was deafening.

The sky above was blue, but the atmosphere was increasingly turbulent. As the plane pitched and yawed, the flight attendants staggered down the aisle. I glanced over at Steve and Ed. They were sweaty and fitful. Soon enough, we began our descent into Winnipeg. The lower we flew, the more the plane rocked. The clear sky turned brown and opaque from the dust kicked up by the wind. As the city became visible, we could see trees heaving in the gale. Car lights were on.

When we approached the runway, there was a sudden thump, and the plane veered to the right. My stomach hit my mouth, and I grabbed an air-sickness bag, just in case. The shrill conversation of the teenagers stopped abruptly, and someone screamed “We’re gonna crash!” At the last moment, the engines behind us roared and we were back in the air. The force of it pushed me back in my seat.

The pilot was determined to try it again, though. Down we went. I looked for the flight attendants, but they’d disappeared. A puff of black smoke flew at us as we slammed down, then bounced up, then down again. As the pilot cut the engines, a gust caught us, rocking us from side to side, the luggage knocking in the overhead carriers. It was like being on the Scrambler at the carnival, except that the momentum was tenfold.

When the plane lurched to a stop, the cabin erupted in cheers. I did not join in.

Entering the airport, we saw that we were alone. The lights were dimmed. A couple of security guards were standing nearby, and when I walked past them, they greeted me.

“Welcome to Winnipeg,” one of them said, with an ironic grin. “We were afraid you weren’t going to make it.”

“What happened here?” I asked one of them, gesturing toward the empty hallways.

“We’ve been shut down for hours. All the flights got re-routed to Regina. That pilot of yours, he must have a hot date in town.”

I looked for Ted and found him seated near the restroom, his face ashen.

“Nothing personal, but I’m never going on another trip with you guys,” he said.

By Jeff Hicken