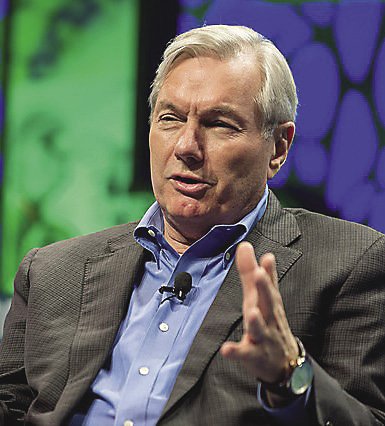

Dr. Michael Osterholm is deeply concerned that overall efforts to halt the spread of Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) in captive and wild populations of deer, elk and other members of the deer family, known to zoologists as cervids, fall far short of what is needed to limit the spread among cervids and prevent potential transmission to humans.

An expert in infectious disease and a public health scientist, Osterholm is the director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota. During his career, he has addressed world health issues such as biosecurity and antibiotic resistance, as well as diseases including HIV, influenza pandemics and Lyme disease. He frequently consults with national and international health organizations.

Thus far, CWD is found in cervids only, but Osterholm believes the disease poses a serious risk to human health. In Great Britain, a related brain disorder in cattle, commonly called Mad Cow Disease, was transferred to people during the 1980s and 90s after disease-contaminated beef products entered the human food supply. Osterholm said existing research about the risk of transmissions to humans isn’t conclusive. However, he predicts CWD will follow a similar path as Mad Cow Disease.

“I believe it’s just a matter of time until there is a deer-to-human transmission,” he says.

Osterholm’s prediction is based upon his knowledge of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE), a degenerative brain disorder that creates tiny, sponge-like holes in brain tissue. CWD is a variant of the disorder, which includes the aforementioned Mad Cow Disease, scrapie in sheep and Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease in humans. These illnesses are caused by a modified form of a protein known as a prion. Scientists don’t understand why these prions enter and wreak havoc in the central nervous system. What they do know is that prion diseases are always fatal. The World Health Organization has recommended keeping agents of prion diseases out of the human food chain since 1997.

Osterholm is concerned that many politicians and regulatory agencies are not taking the actions necessary to limit the spread of CWD in deer populations or prevent CWD-contaminated venison from entering the human food chain. Outbreaks of CWD seem to be accelerating in wild cervid populations across the U.S., often in the vicinity of where the disease was initially discovered on cervid farms. Osterholm and many wildlife biologists believe the movement of domesticated deer and elk among commercial operations has carried CWD across North America.

“When you look at the management of cervid farms, there is limited meaningful enforcement of regulations regarding the movement and containment of animals,” he said. “When captive animals break out of containment areas, this is the perfect situation for spreading the disease to wild cervids.”

In Minnesota, farmed cervids are regulated by the state Board of Animal Health. Wild cervids are the responsibility of the Minnesota DNR. A 2018 Legislative Audit was critical of the BAH’s CWD enforcement and record-keeping related to deer and elk farms in the state, concluding with a list of recommendations for the agency to improve its performance.

“The Minnesota Board of Animal Health has been a day late and a dollar short in enforcing the containment of farmed cervids in Minnesota,” Osterholm said. “The captive cervid industry keeps making excuses for years to protect deer farmers, which is plain B.S.”

Since 2002, CWD has been found on eight Minnesota deer farms, according to the DNR website. CWD was first found in a wild deer in 2010, within two miles of a CWD-positive elk farm in Olmstead County. Three years of intensive surveillance with the DNR testing over 4,000 deer did not turn up any more positives. Because CWD was present in bordering counties of Wisconsin and Iowa, the DNR began voluntary (for hunters) surveillance of wild deer in southeastern Minnesota in 2016, finding three CWD-positive bucks near Preston in Fillmore County. Special hunts and culling in early 2017 turned up eight more positives. Intensive surveillance has continued finding positives since then, as well as a 2018 discovery in adjacent Houston County, possibly indicating the outbreak is growing.

The DNR created a CWD Management Zone to contain the outbreak, with strict restrictions on feeding deer or moving cervid carcasses. The agency is holding special hunts and taking steps to reduce the deer population in what is some of the state’s best whitetail habitat. Osterholm praised the DNR’s CWD response.

Unfortunately, neighboring Wisconsin seems unable to contain the spread of CWD in wild or farmed deer. First discovered in 2001, the disease has now been detected in 23 of 72 Wisconsin counties. In some counties, CWD appears to be endemic in the wild deer population.

“As far as I’m concerned, the Wisconsin deer herd is lost and gone,” Osterholm said. “Wisconsin’s CWD response has been irresponsible. I’m not sure what they can do now.”

The prevalence of CWD in some of Wisconsin’s wild deer populations presents a human health risk. It is inevitable the CWD-positive venison will wind up on somebody’s table or perhaps a lot of tables.

“Think of all the sausage production out there,” Osterholm said. “When you consider what happened in England with Mad Cow Disease, I worry desperately about all of these meat processors.”

The misshapen prions that cause TSEs contaminate the environment. He said that when surgeons operate on a patient with the similar TSE Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, hospitals remove all of the equipment associated with the procedure, so it is never used again. Meat processors can’t effectively decontaminate their facility after processing CWD-positive deer. That may mean other products produced there are contaminated with CWD prions. Osterholm said prions can persist in the environment for hundreds or even thousands of years.

“Given my experience with prion diseases, what we are doing right now is Russian roulette,” he said. “We haven’t given enough due to what CWD may do to human populations.”

SIGN UP to receive Shawn Perich’s Points North

articles in your inbox.