I’m fascinated by place names, so I looked into the history of our town soon after we moved to Duluth. The first European to pass through here was named Daniel Greysolon, Sieur Du Lhut. Mangle his title of nobility to get Duluth and suddenly, my address on Greysolon Road made sense.

Fast-forward 15 years to August, 2016. My family planned to visit my parents in Maine. We saw a chance at some junior varsity international travel and decided to drive a rental car to Quebec City. Then, I had an idea: I wanted to check out Montreal, Greysolon’s launching point in the New World. It would only take an extra day and I thought I could find where he was buried.

The broad strokes about Daniel Greysolon are easy to figure out. He was born in France in 1639 and had the noble title of Sieur (Knight) Du Lhut. He served in the French Army. After the bloody battle of Seneffe in the Franco-Dutch War in 1674, he traveled to Montreal in New France. He went west from Montreal in the fall of 1678. The Anishinaabe called the site of present-day Duluth onigamiinsing or “at the little portage.” He portaged over Minnesota Point (near where the famous Aerial Lift Bridge now stands) on June 27, 1679. He famously recovered Father Louis Hennepin, who was held captive by one of the Sioux tribes and explored some of the country along the Mississippi River. He went all the way back to France in 1681 to defend himself in court from accusations that he was a renegade fur trader. He came back to Montreal in 1682. From 1683 until 1689, he helped strengthen and build forts from Thunder Bay to Michilimackinac to Fort St. Joseph. He spent the rest of his days primarily in Montreal until he died of gout on the night of February 24, 1710.

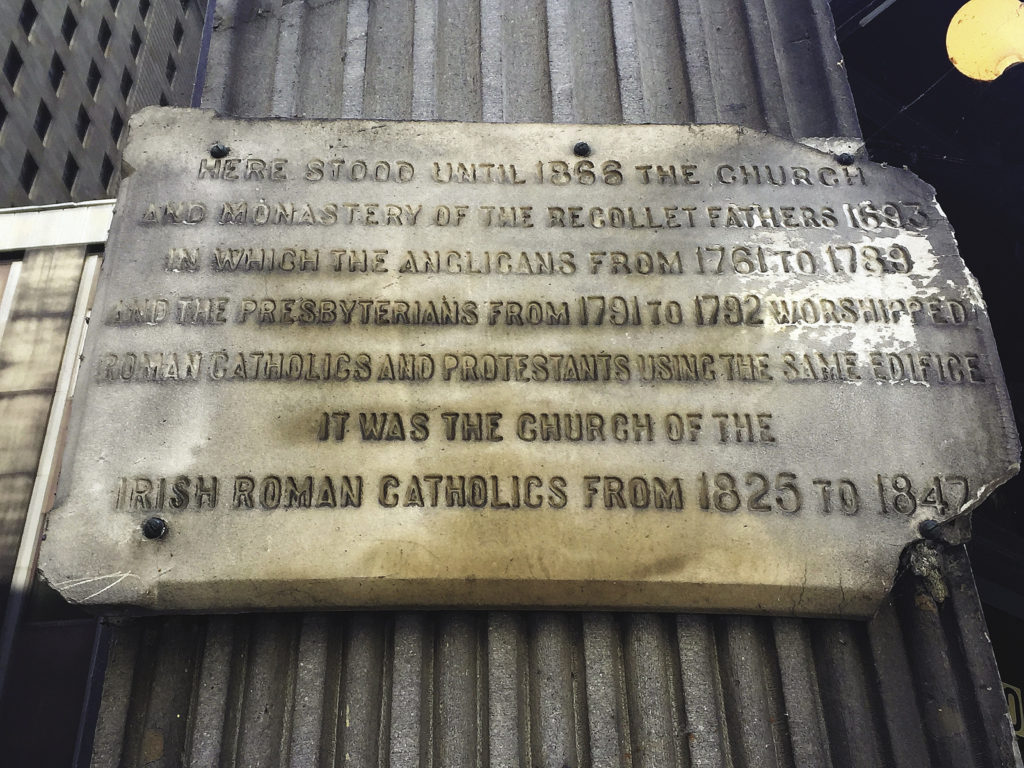

Then, the all-powerful Internet let me down. It seemed simple: Drive to Montreal and find Greysolon’s final resting place. I learned that Greysolon was buried in the Church of the Recollets in 1710. I finally found a Church of the Recollets in Old Montreal. This part of the very heart of Montreal now only exists as lines on a map. Much of the current city was built over that old part of the town in the late 1800s. The Church of the Recollets was knocked down in 1867 to make way for the current building at the corner of Rue Notre-Dame and Rue Sainte-Helene. I found three historical plaques erected in Montreal about Daniel Greysolon. Another source led me to the address of the house where he died.

My adventurous family agreed to indulge their father with a walk to these four spots, finishing at the one-time resting place of Daniel Greysolon. So, we saddled up in a Ford Escape and drove north. The kids, feeling French, pronounced it, “Es-CAH-pay.”

We woke on a sunny, warm day in August and walked a clockwise path around Old Montreal, starting at the Place du Jacque Cartier. The first plaque we visited was on the side of an Italian restaurant, at the corner of Rue Saint-Paul and Rue Saint Charles. Because of my computer research, I knew that it was on the site of a stone home that Greysolon built. Ultimately, he sold the home and it became the site of a new, fancier home for the governor of New France, called the Chateau de Vaudreuil. You can infer from a couple sources that Greysolon built the original home around 1675 to impress a young woman he was courting. But they broke up. Then, he left town for the west to become a coureur de bois (woods runner), less reputable than the later, licensed voyageurs. The things guys will do for a girl; and then do to forget a girl.

Then we walked along Rue Saint-Paul. One account of Greysolon’s last days said he died on the present site of 60 St. Paul Street. We stumbled around the middle of an intersection, looking more like tourists than normal, until we finally agreed that there was no 60 St. Paul East. So, we walked down the picturesque street until we found an art gallery at 60 St. Paul West. Once again, the current gray, stone building was built in the 1800s. We had to imagine him in the bottom floor of a house on that site that he rented from Charles Delaunay, a tanner. One account said he had a nice view of the St. Lawrence River from one side and, from the city side, he could see the house he built and sold to Governor Vaudreuil. It was hard to imagine the smaller, older Montreal without a time machine. Was that really the home where Greysolon died? Was there a 60 St. Paul East long ago and that was actually the spot?

We turned the corner onto Rue Saint Sulpice and we saw the towers of the Notre-Dame Basilica of Montreal. Just across the street to the east of the basilica, we found the only plaque in Old Montreal that specifically mentions Daniel Greysolon. It’s on the site where Greysolon rented a house in 1675, before he built his own stone home. The inscription in French translates as, “In 1675, Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut, gendarme of the King’s Guard, explorer and runner of the woods lived here and died in Montreal in 1710.”

We snapped a picture and then stood in the Place d’Armes square in front of the basilica. It was impressive. Normal people probably would’ve paid to go inside the church where Celine Dion got married. Or been awed by the statue of Maissoneuve, the founder of Montreal. But not us. We had to find Greysolon.

Just a few blocks away, we reached our last landmark: the site of the Church of the Recollets where Greysolon was buried in 1710. I took a picture on that street corner at the intersection of Rue Notre-Dame and Rue Sainte-Helene. That whole city block used to be the church grounds. Old paintings and photos show an impressive building. After the English conquest of New France, the Anglicans used the church and then many other denominations did, until the church was torn down in 1867. The new building was essentially a department store. I had no idea if Greysolon was still there, somewhere underground, or if he’d been moved.

We drove away to the northeast toward Quebec City just a few hours later and I thought about our morning. It was possible we were the only people who ever tried to find Daniel Greysolon. I thought it was even more possible that we were the first and only Duluthians to ever make that pilgrimage and walk to those four spots in Old Montreal. I call that an adventure. My daughter gently corrected me and said that it’s more precise to call it a quest. Either way, I was pretty happy.

The feeling didn’t last. After several days in Quebec and returning to Maine, I felt like my quest failed. I started poking around the Internet again. I wrote to the Notre-Dame-des-Neiges Cemetery. They didn’t have him. They recommended next door at the Mount Royal Cemetery. They told me he wasn’t buried there.

I wrote to the Order of Franciscans in Quebec, since the Recollets are from that tradition. I did my best to use a little French in my emails and they did their best to use a little English. A woman named Claudette Vaillancourt, an archivist there, sent me a document in French that showed the details of the construction of the building over the church. And she said, “Yes, people were buried under the convent there.” A victory, of sorts. But were they still there? Was Greysolon still there?

Then, finally, an answer came to one of the first questions I asked. Gary Schroder, president of the Quebec Family History Society said it was possible that his body remains where it was originally buried. So, maybe he was buried just a few yards away from where we stood on Rue Notre-Dame. Maybe he wasn’t. The real question is: Does it matter?

He ranged far and wide in the New World. A lifelong soldier and explorer that many sources claim should be more famous. Some writers remarked that he was modest. Maybe that hurt him in a world where showing off for royalty was required to make it big. He certainly didn’t earn a permanent grave site.

The Marquis de Vaudreuil, the Governor of New France, gave this simple eulogy: “He was a very honest man.” That, and having a city named after you, might be better than a gravestone. Especially if the city is as cool as Duluth.