One of my earliest memories dates back to when I was four years old. I watched my father lift a skillet full of beef tongue from the stovetop as I stood in the middle of the kitchen. I remember being perplexed and sufficiently turned off by this foreign, featureless mass of meat flanked by onion halves and potatoes. What I don’t remember is eating it for dinner that evening. But apparently, I did.

“Oh yeah, you ate it. Sure, you ate it. You’ve had it two or three times. You probably didn’t know what it was,” my dad assured me, as he recounted our shared memory over the phone. He then began to recall stories of his own childhood, growing up throughout the 60s in the Canadian prairies as one of four sons to Dutch immigrants.

“In the day it was cheap. It was like a staple: you had tongue one day, and your meat loaf the next…and that was what people lived on. Before I was 13 years old, we never had the stuff in the grocery store like we have now. That was what we grew up on,” he told me.

Many of us have stories of ourselves, our parents or grandparents who valued the odd parts of animals. In times of scarcity—or by virtue of culinary creativity and ethnic tradition—using the whole animal simply made sense.

Turning to wild game, I have taken a personal interest in venison heart—motivated in part by curiosity and inspired to honor the animal’s life by using what I harvest. As my partner and I field-dressed our first buck last November, I carefully cut away the connective tissue to free the heart from the rest of its insides, still warm in the early snow.

A commonly-consumed organ of white-tailed deer, there are myriad ways to prepare venison heart for the dinner plate: stuffed, roasted, braised, grilled or simply sautéed.

Heart is typically unlike most choice cuts of meat in both taste and texture—it’s a massive piece of muscle, after all. But with scrupulous preparation, many people love it, including Tom Armstrong. An avid Thunder Bay hunter, he’s been eating bread-stuffed deer heart for years according to his mother’s recipe.

“My grandpa loved to eat [heart] and my mom would usually cook it. The only organs I’ve eaten are the heart from deer and moose, [but] I’ve kept the liver and tongue for others,” he tells me.

Organ meats, including the heart, are high in many vitamins: B and fat-soluble A, D, E and K, according to Catherine Schwartz Mendez, public health nutritionist with the Thunder Bay District Health Unit. “Also, minerals like iron, phosphorus and magnesium,” she adds.

While the nutritional benefits of organ meats make them revered as a delicacy, care should be taken when harvesting them from the wild.

“Signs of unhealthy organs are typically discoloration, presence of cysts or abscesses, excess fluid around the organ and foul smell,” says Michelle Carstensen, wildlife health program supervisor with the Minnesota DNR.

It isn’t uncommon to find parasites or cysts living in white-tailed deer. Some can be seen with the naked eye, including liver flukes, which primarily infect the liver but can migrate to other areas and encapsulate themselves in the abdominal lining and wall of the chest cavity. Others including tapeworms (Taenia krabbei) can infect muscle tissue, including the heart.

The good news is that these parasites pose no health risk to people if properly handled. Carstensen recommends wearing gloves when field dressing, cleaning and disinfecting field dressing knives prior to butchering the meat and freezing wild game down to -4 degrees Fahrenheit for a minimum of four days to kill parasites. Cooking temperature should be to at least 165 degrees Fahrenheit to kill unwanted bacteria and parasites.

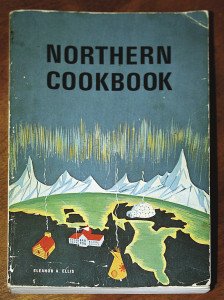

When I brought up the idea of cooking venison heart to my grandparents (my dad’s parents—the ones who love beef tongue), my Oma shot up from her chair and exclaimed she had “just the book” for me. After rifling through a shelf above her kitchen stove, she came back to the table with an old paperback dated from the 1960s called Northern Cookbook, issued under the federal Ministry of Indian Affairs and Northern Development.

“The purpose of this book is to record facts about some of the wild game, game birds, fish, fruit and vegetables available in Canada’s north,” prefaces the author, Eleanor A. Ellis.

From jellied moose nose to boiled reindeer head, this book will satisfy the appetites of the brave, the curious and the unconventional. It’s also a testament to the history and culture of people so intimately tied to the land that times of need or scarcity were met with tenacity, creativity and reverence.

If you have what you consider to be an unconventional wild game recipe to share (venison heart or other), feel free to share it by emailing julia@northernwilds.com.

Braised Heart of Venison

Braised Heart of Venison

1 venison heart

1 tablespoon salt

4 tablespoons flour

1 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon pepper

3 tablespoons bacon fat

Water

1 cup diced carrots

1 cup diced celery

1 medium onion, sliced or 2 tablespoons dried onion flakes

2 tablespoons dried parsley

Wipe the heart well with a damp cloth. Soak overnight in enough water to cover, to which 1 tablespoon salt has been added. Remove, drain and pat dry. Slice heart crosswise in ½ inch slices and remove the tough white membrane. Dredge the slices in flour. Melt the bacon fat in a heavy fry pan and sauté the slices of heart, until lightly browned. Add enough water to cover the meat, reduce heat, cover and let simmer for 1 hour, adding more water as required. Add vegetables and more water if necessary, cover, and simmer until vegetables and meat are tender. Serves 4.

From “Northern Cookbook” by Eleanor A. Ellis