When we think survival, we often turn to the four basic needs we rely upon to sustain ourselves: food, water, fire and shelter. Enough food in a balanced diet; clean water to drink; fire for heat and warmth; shelter from the elements.

Arguably the fifth basic need is one that’s at the forefront of fending off illness and disease: hygiene and sanitation.

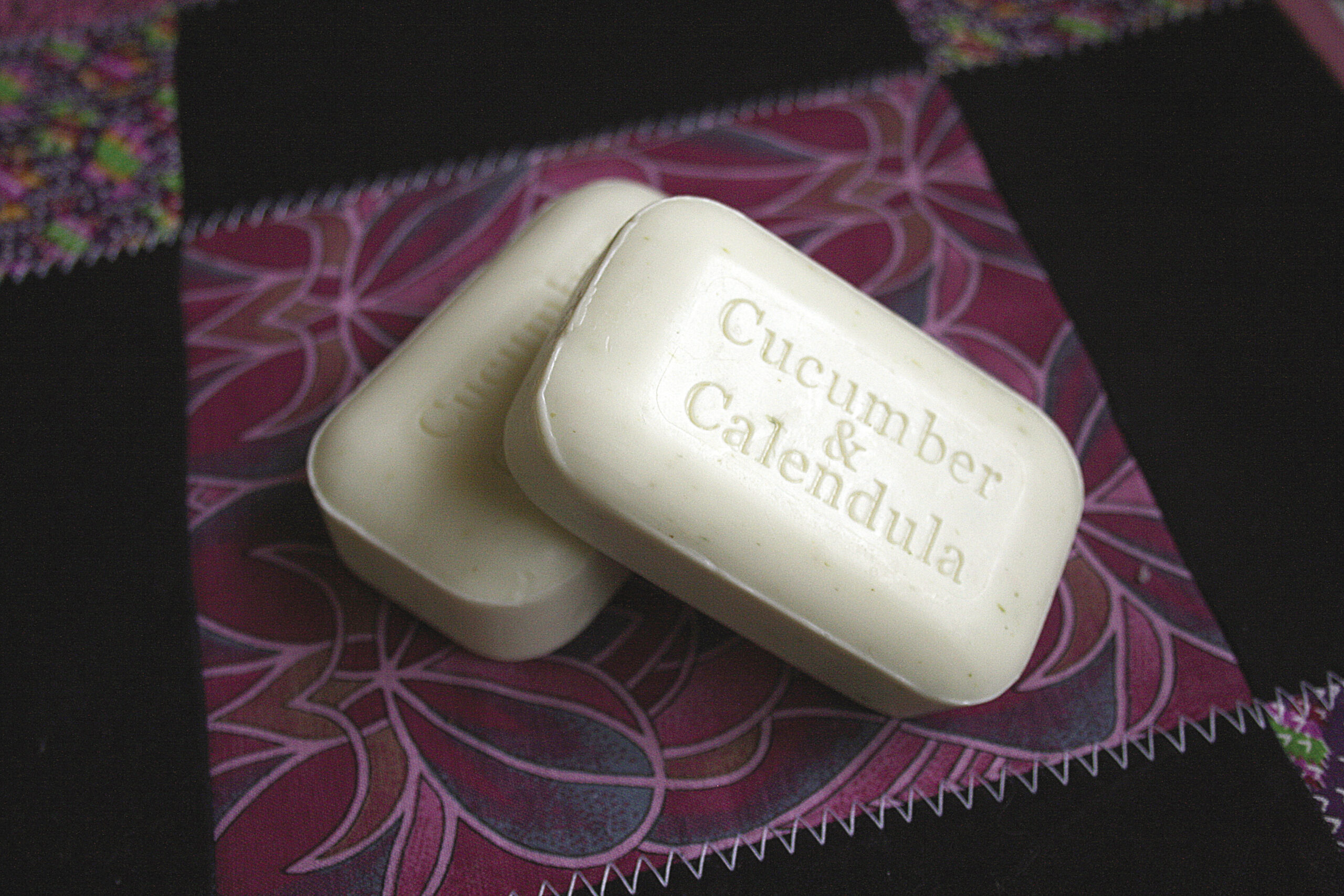

A home apothecary of natural remedies can help treat ailments and ward off infection. But before you go wandering into the woods to gather roots, flowers and leaves for tinctures and healing salves, consider soap and its role in basic hygiene.

It’s hard to say when soap was first invented, although it appears to have been around for nearly 5,000 years if not longer. According to the American Cleaning Institute, evidence of soapmaking was found in 2800 B.C. during an excavation of ancient Babylon. Clay cylinders contained soap-like material along with inscriptions of formulas containing its main ingredients.

In recent history, the use of soap played a critical role during times of war. During the Crimean War (1854-1856), Florence Nightingale and a team of volunteer nurses arrived in Turkey to care for British soldiers. Crowded in hospital rooms without clean bedding or linens, and with medicine in short supply, more soldiers were dying from diseases like typhus, cholera and dysentry than their battle wounds. Nightingale brought in necessities like clean towels and soap, and is remembered for the work she did in educating people on the importance of keeping hospitals clean and free from infections.

Today, most commercial hand soaps contain more than a dozen ingredients—some recognizable, while others like ‘fragrance’ and ‘parfum’ are catch-all terms for undisclosed chemicals. However, basic soap doesn’t have to be concocted in a laboratory, and for people who suffer from sensitivities to fragrance and other chemical additives, that’s really good news. With just three ingredients, soap can be satisfyingly simple to make at home.

Soap is made by mixing fat and water with lye to create a chemical reaction called saponification. Most soapmakers today use sodium or potassium hydroxide as their lye solution, but mixing wood ashes with water is a traditional means of creating this integral ingredient. I’ve never tried the wood ash method with soapmaking, but conveniently a wood ash and water mix is also used to create an alkali solution in the process of making buckskin. So if you’re tanning a deer hide and have extra tallow lying around, you can render the fat and add it to the lye mixture to make soap while you’re at it. Pretty convenient considering that tanning can be a messy job.

I’ll confess that I first “made” soap with a kit from a craft store that literally involved me spending a pile of money on a large bar of hardened soap that I melted down and repoured into molds (with the addition of some nice smelling essential oils and herbs). Without doing much research, purchasing ready-made soap gave me the impression that making it from scratch was somehow too complex in its chemistry to do it myself. After all, soapmaking can be a beautiful art, with ranges of colours, lathers, transparencies, shapes and scents. But after I made soap at a traditional skills workshop this summer (albeit very basic), I was impressed by how simple and accessible this creative process can be.

Since the idea of rubbing boiled mammal fat and wood ashes all over your hands and face is a tough sell these days, there are substitutes. Several types of vegetable fats can be used in place of rendered tallow or lard for a vegetarian or vegan option. Soap recipes differ based on the fat you’re using, and different fats have different characteristics. If you want a soap that forms a lot of bubbles and gives a nice lather, castor, coconut or canola oils work well. Others like jojoba and shea butter are more commonly used in moisturizing soaps.

If you’re keen to try making soap, make sure you’ve got the proper gear and credible recipes. Lye is alkaline and can burn, so you’ll want to work with sturdy containers and mixing utensils; gloves, glasses and covered footwear are a good idea too. And if your soap is too fat-heavy that’s generally okay, but a lye-heavy soap is caustic.

In our hyper-sanitized world of antibacterial soaps and toxic cleaning agents, it’s worth considering the impact that our consumer choices have on public health. Do we need to lather our hands in antibacterial soaps and sanitizers every time we visit a bathroom or public space in everyday situations? Probably not.

The main way to prevent bad bacteria buildup is to have the body house good bacteria in its place, says Jason Tetro, a microbiologist who spoke to CBC News last year about childhood immune system development.

“The first year of life is the most important when it comes to allergies. It seems like breast feeding, getting kids out to play in the dirt and getting exposed to friendly bacteria is the answer,” he said.

Tetro points to the hygiene hypothesis, which claims that the paranoia of having to sanitize everything that humans interact with isn’t allowing bodies to build up immunities.

“Let them eat dirt is what I always say,” said Tetro.

It’s a theory that a growing number of researchers are swearing by. In this case, there’s no need to wash out their mouths with soap.