The adventure was Steve’s idea. My larger-than-life, Falstaffian brother-in-law had gone to the All-Canada Sportsmen’s Show the winter before and met the tour operator. Our destination was Neultin Lake, a giant of 880 square miles, which straddles the border between Manitoba and Northwest Territories, about 900 miles north of Winnipeg. At 60 degrees latitude, it was farther north than any of us had been. Hard to believe, there’s another two thousand miles to the North Pole.

For us, the trip promised trophy fishing—trout, northern pike and Arctic grayling. A few weeks before departure, the six of us, Steve, Fred, Larry, Ed, Miles and I, piled ourselves into a minivan and headed down to the sporting goods store. We were flush with excitement and cash. Lots of friends and colleagues had given us advice on fishing strategy. “You gotta get the ‘Five of Diamonds,’” my lawyer friend David Conn said. It’s a yellow spoon with five red diamonds painted on it. “Kills the lake trout.” Fred insisted on the Red Eye, another trout lure. Ed had it on good authority that the Daredevle—a red and white painted piece of metal—couldn’t fail. We walked down the aisle tossing the merchandise in the baskets. Those colorful lures are designed for the fisherman more than the fish, I think.

We loaded back in the minivan, headed to the bar to talk over our plans. Suddenly, a mindless driver in the opposing lane crossed over directly in front of us. We were forced into the ditch, rolling over and over. When we finally stopped, someone from the back shouted—“Everyone okay?” Incredibly, we were, except for Ed’s van, which was a wreck. It was a dark portent for our adventure.

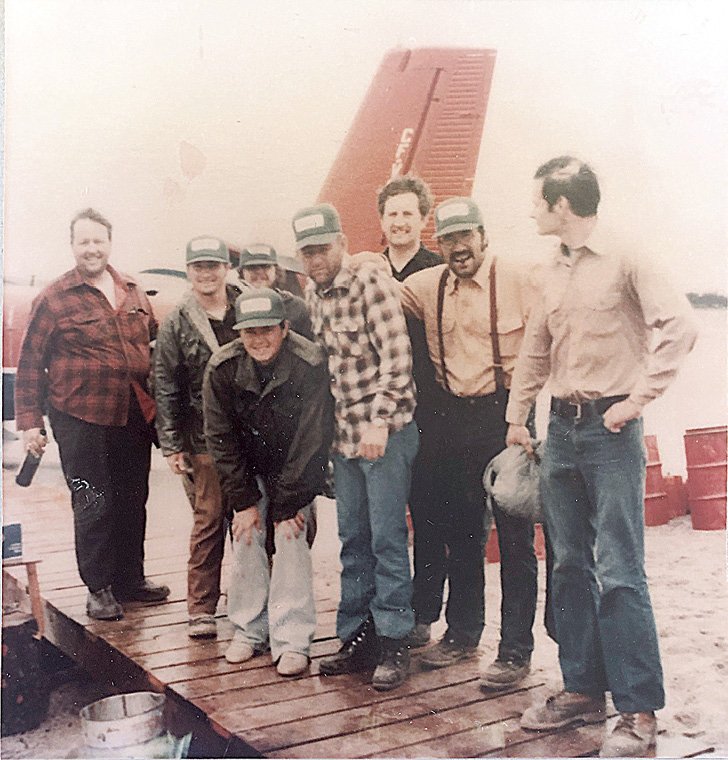

Soon it was August 15—time to go. A six-hour drive from Minneapolis to Winnipeg. Overnight in a motel, and onto an Air Canada 737 for the two-hour flight to Lynn Lake, Manitoba—the northernmost post of civilization in the province. The tour operator had a cab waiting to take us to the lake, where a dozen seaplanes were lined up to transport fishermen to various camps. We hardly saw the little town, although eventually, and unexpectedly, we would.

We were led to a Dehavilland Twin Otter—the workhorse of the Canadian outback—which was tied to the dock. The guide introduced us to Colin, our pilot. He was a wiry Welshman with a curious bare spot on the side of his head. It was, we discovered later, the result of his walking too close to a prop. He was painfully shy.

As we flew northward over the tundra, there was hardly a sign of civilization, except for an occasional abandoned trapper’s shack. In a couple of hours, we splashed into a serene bay and pulled up to our destination. It consisted of two large tents and an outhouse on the end of a sand bar. There was a camp guy waiting for us—Peter.

“Throw the groceries in the hole,” Peter said. We had meat, potatoes, carrots and the like, and the hole was chiseled out of the permafrost—better than any refrigerator. He pointed to our tent—it had bunks for six, a wooden floor and a propane heater. Surprisingly, we used the heater only once, because the weather was sunny and temperate—mostly in the 60s, or even the low 70s.

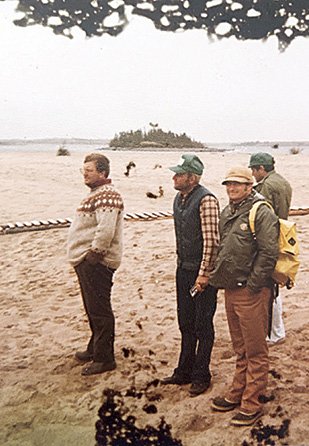

We asked Peter about the fishing. “You’ve got three boats and plenty of gas. Your compasses won’t work. We’re too close to the Magnetic North Pole, so don’t get lost.” We did, of course. The lake was populated by hundreds of islands, which made line-of-sight navigation impossible. We had walkie-talkies, but they weren’t reliable.

One day, Larry and I were catching some good-sized northerns. Before we knew it, it was 9 p.m. That far north, the daylight lasts into the early morning hours, but the sky was darkening. We didn’t know where we were. “Call someone on the walkie-talkie,” I said. There was no answer. We pulled up to an island and climbed to the top, hoping to see the camp, but all we could see were more islands. We motored one way and then the other until sometime after midnight, we finally saw the tents off in the distance. I was so relieved I felt like crying.

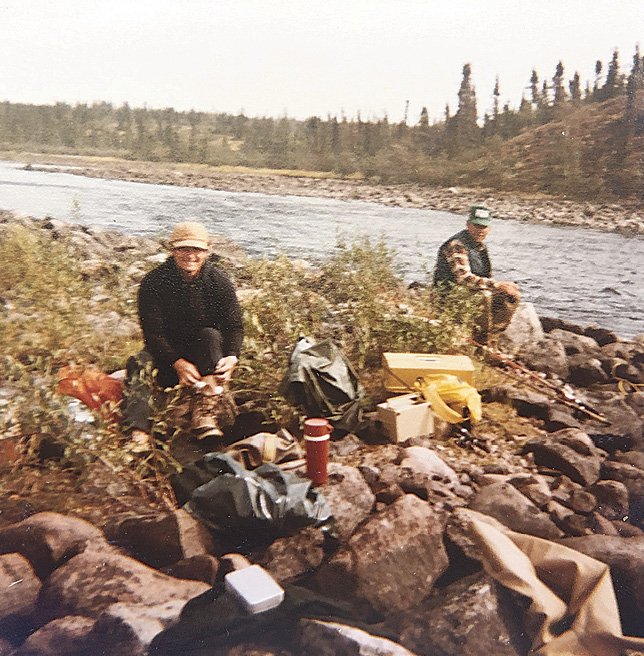

Another day we took the three boats and motored miles away to a river, hoping to catch the exotic Arctic grayling, a small but savage fighter known for leaping out of the water before giving up. As we looked to the shore, we saw piles of caribou antlers. “They come down this far south in the winter,” Peter said, “then they shed them before they head back north in the spring.”

A couple of guys complained about Peter. “What does he do all day while we’re out here on the boats? I thought we’d have a guide.” They were right. Peter was back in camp, talking on the radio with his girlfriend in Saskatoon. He’d gather tinder for the fire from the scraggly pygmy pines, or clean the mess tent, but never went fishing with us.

We didn’t catch any trophies, like the ones pictured in the brochure. I’ve actually pulled in bigger trout just off the shore of Lake Superior. We fought some ferocious northerns—a little larger than the ones in Minnesota. Northerns were nothing new to us, though. The grayling were a treat, but that was only for a day. It was the camaraderie, and the uniqueness of the far north environment, that made the trip memorable.

A storm rose on our last full day—wet, windy and cold. Our serene bay was socked in, so we stayed in the tent, reading books and swapping stories. Tomorrow would be getaway day, but that was all right—we were starting to miss our wives and families. For me, I’d be arriving home on my wedding anniversary.

“I just got a call on the radio,” Peter said at about 10 the next morning. “The pilot’ll be here in an hour.” Although the rain had ended, the storm raged on, and the wind blew harder, creating whitecaps even in our little bay. Colin managed a landing, though, and we loaded up and got in the Otter. Looking at the skies, I wondered. Shouldn’t we have seatbelts? Why isn’t our gear secured? But, like everyone else, I hoped for the best.

The engines revved up, pushing us across the bay. Plenty of room here for a takeoff, it seemed. But Colin saw it differently—motoring us around the point into the main lake, where we were bouncing on 4-foot waves. My normally gregarious companions had become silent. I speculated that Colin needed the waves to get a good lift—after all, we’d packed a lot of heavy gear. The engines roared and we were off. What a relief!

Suddenly, there was a powerful gust of wind, tilting us violently to the left. “We’re going down,” someone shouted. A wing, or a pontoon, had caught the tip of a wave, and we went nose first into the lake.

We flipped upside down, our gear crashing on top of us. Water rushed into the cabin. I lost sight of my companions, who, I learned later, escaped out the back door. I’d been thrown forward, into the bulkhead. The back of my neck hit metal and I was disoriented. The engines had stopped. Underwater it was silent.

It’s often said that time slows down in a crisis, and that’s how it was. My first thought was this: I’m going to die. I’m 33 years old. I have a wife and three kids. Little Liza’s only six months old and I’ll be nothing more than a myth to her. Then it occurred to me—why not try to get out of here?

The water was clear and I could see the empty cockpit ahead. I raised my head, found a pocket of air, took a deep breath, and started swimming. Eventually, I popped out of the cockpit door, gasping for breath. Our overturned plane was below me and the pontoons above. I grabbed one and held on.

A plane with pontoons won’t sink. I didn’t know that before. I saw some of my friends, also hanging on, and started counting heads. I also saw our pilot, Colin, who was separate from the others.

Then there was a large splash—it was big Steve! One of our group, Miles, was drifting away and sinking. It looked like he’d given up and was ready for death, but Steve swam to him and pulled him back. That heroic act snapped us out of our stupor, and we started acting as a team.

We were at least a mile from shore, in freezing cold water. Did anyone know we were there? A couple of guys yelled for help, but it seemed futile to me.

That’s when we saw Peter. He’d commandeered one of the 16-foot fishing boats and was heading toward us. He crashed into the fierce waves, sending spumes of water into the sky every time it hit a swell. He circled the small boat around us, but because of the high waves it started to swamp. We swam out to him and started bailing, by hand.

“I didn’t hear you fly over the camp, so I figured something was wrong,” he yelled over the wind and the rolling waves.

Finally, we boosted Ed and Miles into the boat, and Peter headed toward a rock reef near our protected bay, where they were perched until Peter returned to shuttle the next two, Larry and I, away from the plane.

When we got to the reef, I noticed my boatmate Larry. He was hunched over and his skin had a grayish pallor. Exposure can be as fatal as drowning and there was no shelter for us. I was worried about those who were still back at the plane, but even more so about Larry.

Eventually we all made it back to camp. Because of the excitement, I hadn’t even noticed the cold, but now we were a shivering crew of survivors. We zipped up the tent, pumped up the propane heaters, and Peter cracked open his secret stock of Scotch whiskey. “It’s on the house,” he said. By the time a rescue plane reached us, we were drunk as lords.

Three hours later we were in Lynn Lake, meeting with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, which had already started an investigation. The rescue plane had brought some flight suits for us to wear, but a call to the Hudson Bay Company store produced a manager who unlocked the doors so we could get dry clothing.

Someone found us some rooms in a scruffy motel until the next morning. We found a bar full of locals. The burgers were juicy and the beer was sweet. We shared our versions of what had happened, reveling in our own accomplishments and teamwork, like soldiers who had won a battle. It seemed like each of us had a different experience, but Fred summed it up. “Steve, you saved our lives.”

Our exploits were written up in the metro media, and for years thereafter, people would ask us about the accident. Frankly, it took me a while to get over it, but, eventually, I was back in Canada, flying on float planes and, finally, having some luck with the big ones.

By Jeff Hicken