One of my earliest smelt fishing memories was as a kid, sipping hot chocolate on the banks of the Current River under a night sky.

It was early spring: the snow was retreating, it was after midnight, and crowds of people wearing flashlights and hip waders dipped their nets into the ice-cold Current River, swirling them around like elongated magic wands.

My family had set out for the night with friends of ours, including two girls, Jessica and Martina. The three of us were like sisters growing up; our dads worked on the ice rinks together and our moms, sharing their love of cooking, grew close with each other too.

For us kids, nights like these were exhilarating. When word spread that the smelt were running, we hopped into the car and drove a few minutes downtown to the mouth of the river, knowing full well that we’d be up way past our bedtime. We joined the parties of other people lining the river’s edge to fill our buckets with hundreds of tiny rainbow smelt. With each dip of the net, their silvery bodies flashed and flickered in the moonlight.

Smelt Fish in the Great Lakes

Decades before my first smelt fishing experience, the local fishery was vastly abundant. Native to the north Atlantic coastal regions of North America, and a few lakes in the Ottawa Valley in the St. Lawrence River watershed, the rainbow smelt (osmerus mordax) is actually an invasive species in Lake Superior after being introduced to Lake Michigan in the early 1900s. Competing with native species for food and eating their young, these predatory fish soon spread throughout the Great Lakes.

“Once established, they were quickly able to expand into Lake Superior and the rest of the Great Lakes where they became naturalized and self-sustaining,” said Kyle Rogers, a management biologist with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry’s Upper Great Lakes Management Unit.

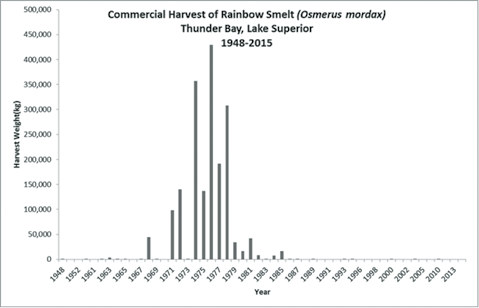

Although Rogers considers today’s smelt populations around Thunder Bay, Nipigon Bay and Black Bay to be healthy, the stock was once so significant that it sustained a local commercial fishery. Seasonal harvest peaked at nearly 450,000 kg in the mid-1970s.

This might explain stories of the heydays of smelt fishing more than 40 years ago. According to lore before my time, it would take just minutes, maybe seconds, to fill a five gallon bucket when the schools ran “thick as thieves.”

In their native habitat, rainbow smelt are anadromous, meaning they spend most of their lives in the ocean and migrate into fresh water to breed. The smelt invasive to Ontario waters can’t return to sea, but they still follow the same behaviour patterns, moving in schools from lakes into streams and along shorelines to spawn each spring.

But after the successful rehabilitation of native lake trout, their numbers drastically declined. By the mid-1980s, the area’s commercial smelt fishery had all but died out.

When I set out to the river mouth this April, I expect to be up all night. I’ll spend a few hours dipping my net, hauling maybe two or three fish at a time. From there, it’s a couple of hours to clean them, followed by a soapy shower for myself so I can wake up smelling decent the next morning. In past years, I haven’t fallen asleep until well past 4 a.m.

The process sounds laborious—and for such a small catch, maybe a little ridiculous. But for me the experience resonates on a more meaningful level: the flash of silvery fish tails as they come up from the water; sharing the night with crowds of other friends and families doing the same thing. And my memories as a kid, when staying up all night in pursuit of these little fish was purely carefree and fun. It’s also a family-friendly fishing activity, costing little more than a fishing license, a net and some hardline determination to wait it out for a decent catch.

When I look at it this way, a bag of frozen fish from the supermarket can’t compare in value. So here’s to welcoming spring on the icy riverbanks, flanking the once-mighty schools of smelt that now trickle upstream. If I can pass the excitement of this tradition onto future generations, then facing the next morning on three hours of sleep is all the more worthwhile.