It seems like every time I open a health magazine or visit a wellness-related website, I find the latest featured superfood: something particularly nutrient-dense, with more antioxidants, vitamins, minerals, enzymes or protein than most of the foods we are accustomed to eating.

Superfoods are usually plants sourced from faraway places: goji berries from Tibet and China, turmeric root from India, spirulina algae from Japan, agave nectar from Mexico—all touted as crucially beneficial for improved health and vitality. These foods have, and continue to be, used by people in their country of origin, espousing a deep connection to one’s heritage and culture. But as their benefits are ‘discovered’ by Western markets, government policymakers must take a cautious approach to meeting global demand.

Take teff for example, a mineral-rich, high-protein grain that is shaping up to be the world’s next superfood. Mostly cultivated in the Horn of Africa, the crop is a crucial food staple that is garnering worldwide attention from those seeking a nutritious, gluten-free alternative to wheat (think diabetics and celiac patients). Relatively unknown outside of Ethiopia, the cereal is predicted to replace quinoa as the latest global superfood, according to a 2014 story published in the New York Times.

Ethiopia initially banned the export of teff to control price hikes and avoid the pitfalls of the quinoa market in Bolivia, where locals could not afford the staple crop after its surge in global popularity. Finally, in May 2015, Ethiopia lifted the ban to prepare for international export of teff flour over the course of the summer.

But what about the superfoods flourishing in our own backyards? Must we source our salvation from cancer, high blood pressure, diabetes and cardiovascular disease from an exotic land? What about the social, economic and environmental impacts that follow? Through education and interaction, wild spaces—both urban and rural—prove that our region is rich in homegrown resilience. As such, it should be treated with care and caution.

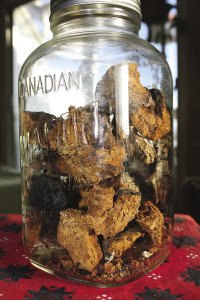

Chaga is a type of medicinal mushroom found on live birch trees throughout the circumpolar boreal forests across the Northern Hemisphere. People have been using chaga as a folk remedy for centuries, but this unpretentious mushroom—which appears as a black, charcoal-like growth, colored golden-orange on the inside—is sparking interest among the medical community in a very big way.

The fungus contains powerful antioxidants and is a concentrated source of betulinic acid, a compound found in various parts of birch trees containing antiretroviral, antimalarial and anti-inflammatory properties. Birch is a hardwood tree of the genus Betula, and research shows that betulinic acid can hamper the growth of tumors, essentially causing certain types of cancer cells to rapidly die of old age.

Carl and Esther Godin own 190 acres of property on their farm outside of Thunder Bay, where they tap birch trees for syrup. The couple has known about chaga for about a decade, but they’ve only recently been infusing the mushroom in birch sap for its synergistic effects.

“There is betulinic acid in the sap of the birch tree, but it’s concentrated in the inner bark. And that’s where the chaga lives,” says Carl Godin.

He and his wife are currently partnering with various organizations to develop a value-added forest product that combines chaga extract with local super-fruits. But like most wild-crafted health foods in high demand, the biggest challenge with chaga is its slow-growing nature.

“That’s the biggest challenge with it, the bioavailability of the betulinic acid from chaga. It grows in the wild, and as far as I’m aware, no one has figured out how to propagate it yet. We harvest it every four or five years from the same tree. When you harvest it, you try to take about 60 percent so that you leave about 40 percent to grow back,” he says. Harvesting in winter, when the tree has gone dormant, is also integral to sustainable harvest.

Cautions like these are echoed by Ontario Nature, a non-profit organization that protects and restores natural habitats through research, education and conservation.

“Trees can be harmed or killed when harvesting chaga if the harvester digs too deep and damages the internal tissues of the tree … Chaga mushrooms take several years to grow and do not grow on every tree, so they must be harvested in moderation and with caution,” writes Mallory Vanier, Ontario Nature’s boreal program intern in Thunder Bay.

From a conservation perspective, forest foods like chaga give reason for protecting wild spaces from industrial development. And in its slow-growing nature, the wildness of chaga offers wisdom: that certain natural processes cannot be replicated, manipulated or synthesized for controlled growth and exploitation (at least for now); and that we, in our motion-obsessed lives, must learn to acquiesce to the cycles and rhythms of Nature.