After experiencing Lake Superior in his 1872 cross-country expedition, Reverend George Grant wrote, “Though its waters are fresh and clear, Superior is a sea. It breeds storms and rains and fogs, like the sea. It is as cold in mid-summer as the Atlantic.” The legends, shipwrecks, storms and rescues of Lake Superior have made for interesting reading—here’s a few vignettes of dramatic rescues where no lives were lost.

The seas were rough and it was foggy in the early morning hours of September 20, 1900 when the 193-foot Canadian steamer St. Andrew, bound for Port Arthur (Thunder Bay) from Jackfish, slammed and stranded on Bachand Island at the entrance to Nipigon Strait. Before a giant wave struck the St. Andrew, three crew members jumped off the ship. Then the ranging seas tore off the pilot house, boiler house and cabins. A towline (hawser) was rigged thanks to the three on-shore crew members and the assistant cook who had bravely swam to shore with the line; the remaining crew used hand-over-hand on the line to get from the ship to safety. The following day St. Andrew sank. It was also the next day that the tug Georgina rescued the crew off the island and brought them to Port Arthur. The St. Andrew was a total loss valued at $50,000 (equivalent to about $1.4 million in 2017).

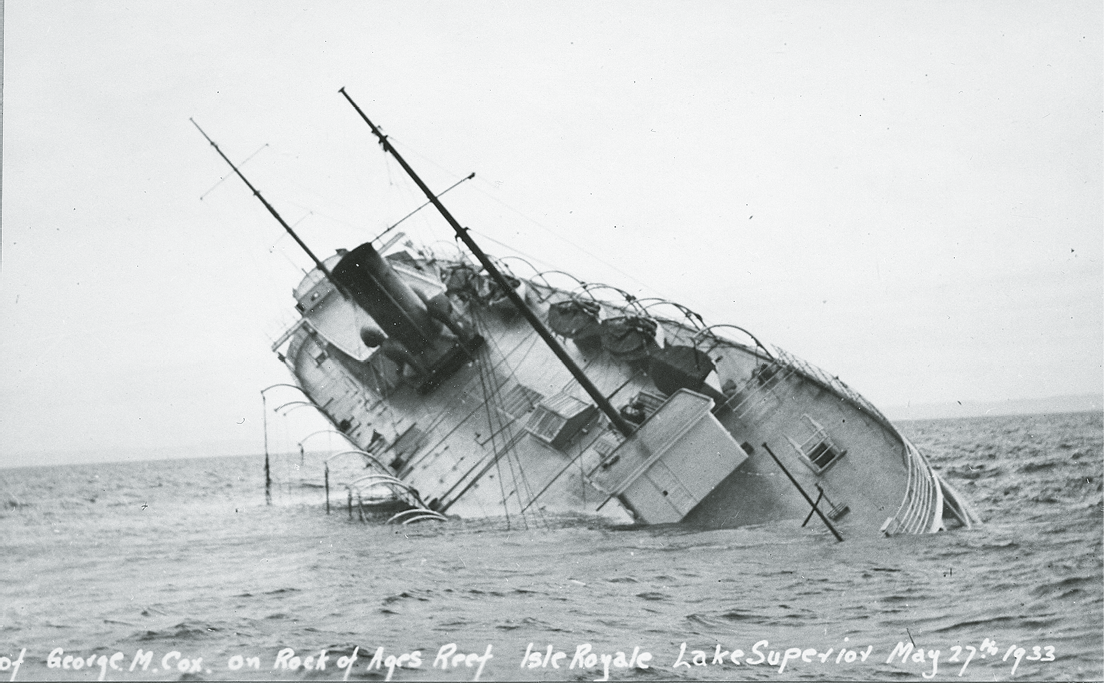

The largest and most successful marine rescue in Lake Superior history occurred on May 27, 1933 off the west end of Isle Royale. No lives were lost when the refurbished and renamed 259-foot steamer George M. Cox (built in 1901 as the Puritan) grounded around 6 p.m. on the shoals near Rock of Ages Lighthouse. Owned by millionaire George M. Cox, his namesake steamer was making her first trip of the season, enroute to Port Arthur from Chicago to pick up 250 Canadians and bring them to the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago.

The SOS message before abandoning ship reached Houghton about 8 p.m. and the U.S. Coast Guard immediately left for a rescue operation, arriving to the wreck about 2:15 a.m. According to the New Orleans Times-Picayune newspaper (May 28 1933),

Plowing through a heavy fog, the steamer, with its passengers at dinner, struck an extended ledge of a rock a short distance from Rock of Ages Lighthouse with such force that her engines and boilers were ripped loose. The impact threw the passengers to the salon floors and sent tables and chairs crashing through the walls.

Before she sank, the 127 passengers and crew had been loaded into life boats and been towed safely to the Rock of Ages Lighthouse by the keeper John Soldenski and his motor boat. A loss of $200,000 (equivalent $3.76 million in 2018), the George M. Cox was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984.

On December 4, 1989, it only took just over three hours from the time the 180-foot U.S. Coast Guard cutter Mesquite hit a reef off Keweenaw Peninsula while pulling a buoy just after 3 a.m. to the order given to abandon ship at 6:17 a.m. As the weather worsened, she was battered by strong winds and waves damaging her hull and flooding her cabins. Mesquite was abandoned after her 53 crew members donned survival suits, took to life rafts/motor surfboats and were rescued by the 700-foot passing freighter Mangal Desai. Unsalvageable, she was removed in July 1990, deliberately sunk in about 110 feet of water and is now a popular scuba dive site of the Keweenaw Underwater Preserve. Mesquite was built in Duluth in 1942 and saw action in World War II.

A dramatic rescue took place June 2016 when things went horribly wrong during a fishing excursion. The water was calm on Lake Superior when Richard Luskleet and son Alex loaded up their canoe at their Portage Bay camp by Black Bay, put on life jackets and headed out to do some fishing. About a half-hour later, they were more than halfway across when the wind picked up, and they decided to return to camp.

Later in a CBC Radio interview, Richard said they just about had the canoe turned around when a three-foot wave picked up their canoe and flipped it over, putting them both in the lake. He was able to get his son into the swamped canoe while he stayed in the water and clung to its sides. After being blown into Black Bay, they dealt with four- to five-foot waves that sometimes picked up the canoe, dumping Alex back into the water.

They stayed positive, reassuring each other that someone was going to find them. Richard had told his wife where they would be fishing and knew she would go for help when they didn’t return. And she did. The rescue operations included off-duty OPP officer staff sergeant Daniel Peters, who took his boat into the rough waters of Black Bay and found the duo in the high seas. By the time they were located, both Richard and Alex had been in the cold Superior water for about six hours.

“We were really in bad straits so they don’t understand how we survived,” said Richard in the radio interview. “I attribute it to both of us just not giving up. We refused to give up and we had a will to survive and really wanted to go home.”