How would you develop a secret code to decipher secret military messages that came in a series of unrelated words in a strange unidentifiable language? Well, the code talkers successfully did during World War I and World War II with codes developed in their Indigenous languages—and no enemy was able to break those codes.

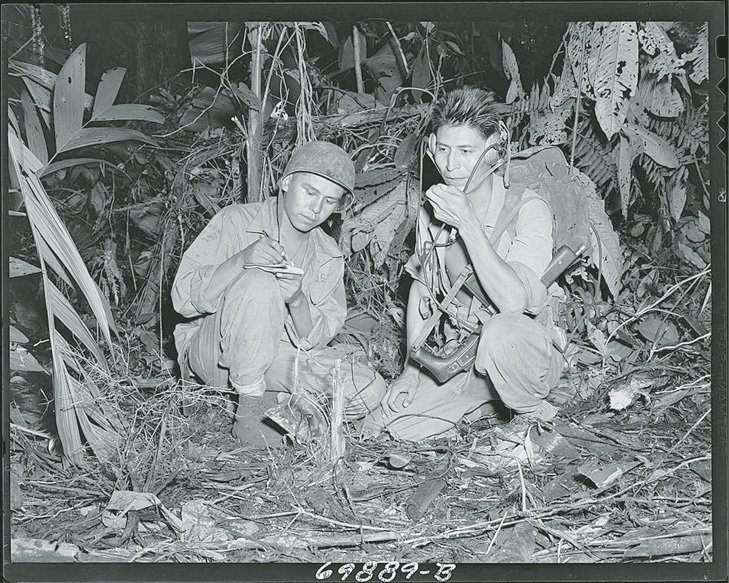

Code talkers were Indigenous soldiers from various native (First Nations) bands in the U.S. and Canada. During WWI and WWII, they developed codes and communicated on radios, telephones and telegraph in their own languages and dialects. Few non-Indigenous knew their little-known difficult language making the codes indecipherable by the Allies’ enemies. Code talkers worked in pairs and took oaths of secrecy which many honoured in their lifetime, never speaking of their work. (The U.S. declassified their WWII code talker program in 1968.)

In the U.S., the Navajo Code Talkers have received the most attention in books, films and media for work in the WWII communications code units; their language has a complex syntax, numerous dialects, and was unwritten at the outbreak of WWII. During both wars, more than 40 native nations transmitted coded messages in different tribal dialects, including Navajo, Cree, Comanche, Sioux (Lakota, Dakota and Nakota), Cherokee, Choctaw, Mohawk, Hopi and Assiniboine. Pioneers in “code talking” were the Cherokees and the Choctaw; the first known official use of Indigenous code was men from Choctaw nation from Oklahoma who worked as telephone communicators (aka Choctaw Telephone Squad) in October 1918 during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

While information about Canada’s code talkers remains sparse with little documentation, the Cree Code Talkers have received recognition. Peter Scott writes in The Canadian Encyclopedia, “Cree Code Talkers were an elite unit tasked with developing a coded system based on the Cree language for disguising military intelligence. They provided an invaluable service to Allied communication during the Second World War. Although their contributions remained hidden until recently, in part because the code talkers had been sworn to secrecy, their service helped to protect Western Allies and to win the war. Indeed, the enemies were never able to break the code.”

So, how did the code talkers work? For Navajo Code Talkers, they would receive a message of Navajo words, translate each one into its English equivalent and then take the first letter of the English word to make the code word. For example, the Navajo word “shush” would mean ‘bear’ in English and so the first letter “b” would be part of the code word. According to Stephen Pincock’s book Codebreaker, the Navajo code for “navy” would be “nesh-chee” (nut); “wol-la-chee” (ant); “a-keh-di-glin” (victor); “tsah-as-zoh” (yucca)—the result: N(nut) A(ant) V(victor) Y(yucca).

Because many military terms—like words for tanks, machine guns, bombers and fighter planes—didn’t exist in Indigenous languages, the code developers made up new terms to use in the language of the code talkers. For example, in Navajo, no word existed for “submarine,” so code developers agreed to use Navajo terms “besh-lo” which translated to code word “iron fish;” the Cree word for mosquito “sakimes” was used for the military term “Mosquito fighter-bomber;” and Comanche code terms for “tank” was “turtle” and “machine gun” was “sewing machine.”

Code talkers played crucial roles in battle. During the first two days at Iwo Jima, six Navajo Code Talkers worked 24-hours around the clock, sending and receiving more than 800 messages, all without error. The signal office Major Howard Connor later declared, “Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima.”

Few of Canada’s code talkers are known by name and one reason may be their oath of secrecy. “The majority of them carried the secret with them to their grave, not even telling their closest family members. The government lifted the commitment to secrecy in 1963, but that information either did not reach many of the veterans or their experiences in the war and treatment upon their return home was so painful they could not share.” (Scott, The Canadian Encyclopedia). All of Canada’s Indigenous code talkers, which included Cree, Ojibwe and other First Nations, have now passed on.

A Canadian Cree Code Talker—Corporal (retired) Charles Marvin “Checker” Tomkins, a Metis from Alberta—did share his story with two documentarians from the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian shortly before his death in 2003 at age 85. Before their visit, Tomkins had honoured his oath of secrecy and never talked about the war, even to his family. Tomkins, who helped develop the Cree Code and worked with the U.S. 8th Air Force in WWII, is featured in the 2016 short documentary “Cree Code Talker.”