The Mountain Portage trail at Kakabeka Falls Provincial Park is 1.25 km long on a hard-packed, easy-walking gravel trail. | ELLE ANDRA-WARNER

People were making history here in our Northern Wilds well before there was England’s Stonehenge or Egypt’s Great Pyramids. For example, back more than about 9,000 years, mystery miners were digging for copper at Isle Royale. Around that same time on a glacial beach on Lake Superior near Thunder Bay, at what is now called the Lakehead Complex, circa 7,000 B.C., Paleoindians had quarry workshops and habitation sites. Standing on the original grounds of history can evoke a closer connection with, and curiosity about, the past. Here’s a few of the less-known original sites in our area.

Did you know there is an original site right in Thunder Bay where three forts were built, the earliest dating back 338 years? Locals may remember back 44 years ago when the reconstructed fur-trading post Old Fort William was opened in 1973 (now called Fort William Historical Park, it features 46 buildings to depict the fort in 1816). It was located nine miles downstream from the original location in 1803 at the mouth of the Kaministiquia River, now a CPR Railyard in Thunder Bay’s East End. Now marked with a plaque installed in 1914, the fur-trading history at the original site actually goes back to 1678-69 when Daniel Greysolon, Sieur de Luht (City of Duluth named after him) and his brother Claude Greysolon, de La Tourette, built the first trading post on northwest Lake Superior, Fort Caministigoyan. Replaced in 1717 by a stockade fort built by French officer Zacharie Robutel de Le Noue, it was used from 1727-43 by the famous explorer Pierre Gaultier de la Verendrye as a trading post and base of operations. And then in 1803, North West Company (NWC) launched its new grand inland headquarters here, christening it Fort William. When NWC and Hudson’s Bay Company merged in 1821, it became a HBC fort.

A plaque at the end of McTavish Street recognizes the site’s history to 1803.

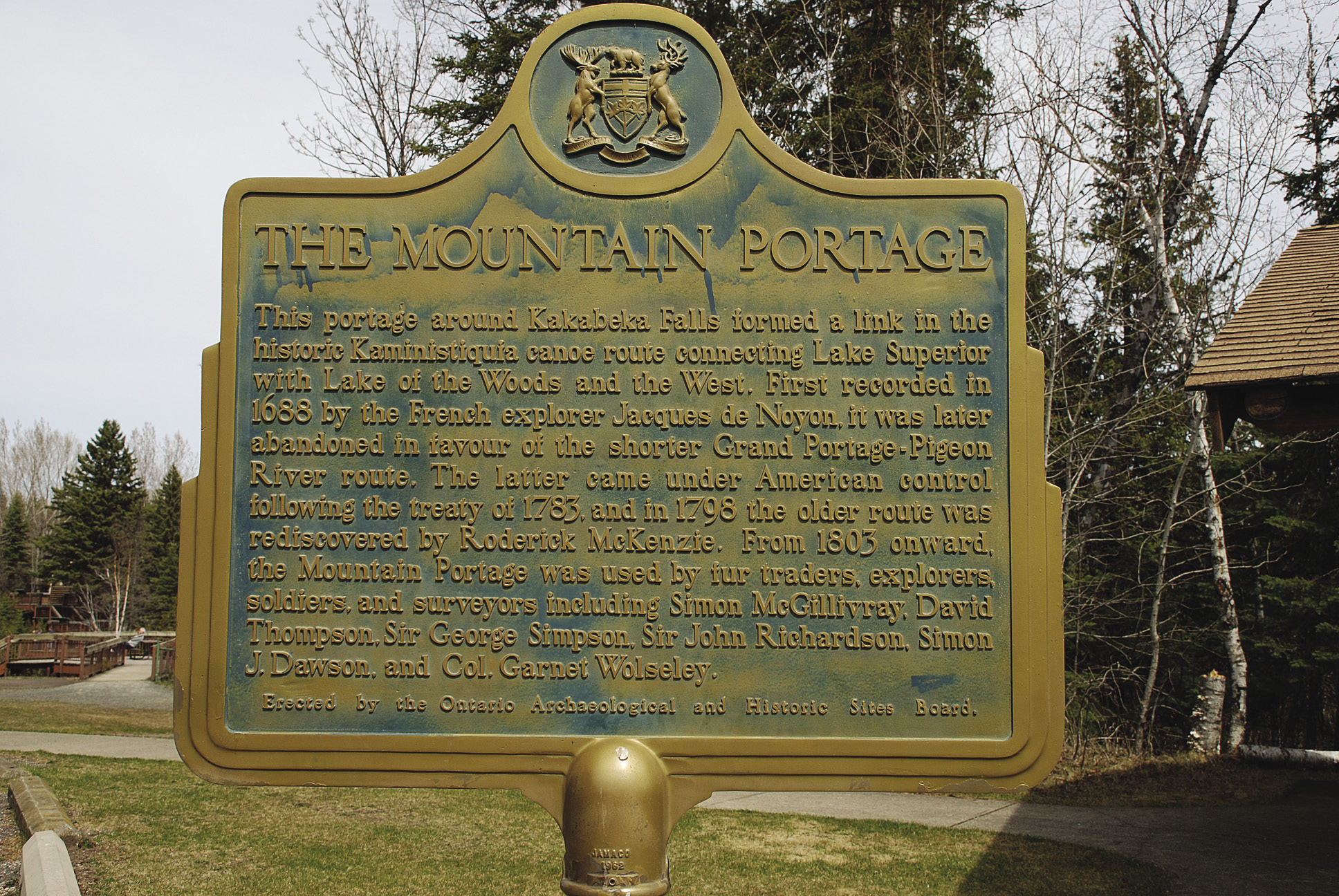

Northern Wilds waterways have been at the crossroads of fur-trade river routes since the 1600s, including the Kaministiquia River canoe route connecting Lake Superior with Lake of the Woods and the West. One of its grueling portages was at Kakabeka Falls’ Mountain Portage, first recorded in 1688 by the French explorer Jacques de Noyon. It was later abandoned for the shorter Grand Portage-Pigeon River route, and put into use again in 1803 onward. Today, visitors at the Kakabeka Falls Provincial Park can leisurely walk part of the original portage route on a wide, hard-packed gravel trail with viewing platforms along the way. It’s on the same route once used by fur-traders, explorers, soldiers and surveyors like David Thompson, Sir George Simpson and Colonel Garnet Wolseley.

One of the river routes that does not get much attention is the Nipigon River Route to James Bay. About seven miles north of Nipigon on Lake Helen, at the small Five Mile Park jutting out from Highway 11, there’s a historic plaque that tells about the well-travelled route that passed right by the park. Used by Indigenous people for eons, then later by fur-traders and explorers, looking out on those same waters brings home the importance of these river routes to the area’s history.

Prince Arthur’s Landing and McVicar’s Creek areas share an interesting event in 1870. Imagine, more than 1,200 British soldiers and Canadian militia camped for a time here with 150 horses, 36 oxen, 50 wagons, 30 carts, and 150 boats, as well as cannons, equipment and supplies. They arrived by steamships and because of shallow water at the dock, were “off-loaded and carried to land on a scow fifty-five feet long and fifteen feet wide that bore the name Tiger Lily” (Neil McQuarrie, The Forgotten Trail, p. 46). This was the Red River Expedition with British Colonel Garnet Wolseley in charge, heading out to present-day Winnipeg to put down the rebellion led by Louis Riel. Wolseley is credited with giving the name Prince Arthur’s Landing to the tiny, fire-ravaged settlement of about 200 people and a few buildings.

There’s another interesting tidbit about McVicar’s Creek, this one connecting with one of the famous original Canadian Mounties, Major James Morrow Walsh, and the elegant McVicar’s Manor (until recently a B&B) built by the creek at 146 Court Street. Besides being a pioneer in policing the Canadian West, the Major gained international attention for his friendship with Chief Sitting Bull when the Sioux Chief took refuge in Canada after the Battle of Little Bighorn, aka Custer’s Last Stand. Built in 1906 on a near-acre lot beside the creek, the Manor was home to the Major’s brother Louis Walsh, a coal tycoon who, along with another brother Philip, partnered and worked with the retired Major in the coal business. In the Major’s July 26, 1905 newspaper obituary, it noted that the he worked with his brother Louis “in the coal trade up to the time of his death with Headquarters in Port Arthur.”