Although it’s with heartfelt human compassion to be drawn towards the sight of a lone deer fawn, bear cub or moose calf; the opposite holds true from the wildlife’s perspective. Assuming that a young animal has been abandoned is rarely the actual case. Many animal species will leave their young unattended for long periods of time.

For example, a doe will not stand over its fawn and advertise its location—rather, it stays in the outlying vicinity to draw the attention of all would-be predators away from the fawn. Since a fawn is born without scent, its main survival strategy is to keep motionless and silent until the doe returns, several hours or days later.

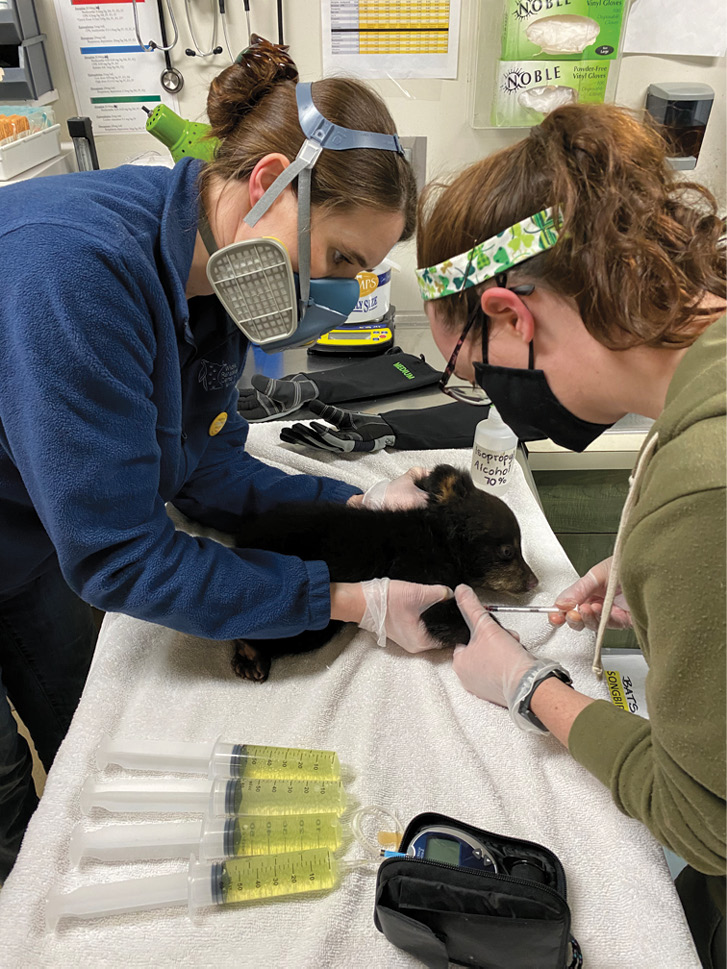

“Before moving an animal, always call us first to triage its condition,” says Brittney Yohannes, communications director at Wildlife Rehabilitation Center of Minnesota in Roseville. During a fawn’s initial four to six weeks of life, it’s “parked” by its mother, meaning it stays in one spot. If you come across this, give it distance and especially keep your dog away from causing it any undue stress.

A healthy fawn should be in a curled-up position with its ears upright and slightly trembling. If it is stretched out or laying on its side and the ears are wilted, then it’s dehydrated and needs urgent care.

The Wildlife Rehabilitation Center of Minnesota requires the animal to be from the central or southern part of the state. “Because of chronic wasting disease, we don’t want to relocate animals from long distances and risk an outbreak into a healthy herd,” says Yohannes. To reach out to the facility, visit: wrcmn.org.

Servicing the northern region is Wildwoods Wildlife Rehabilitation Center of Duluth (wildwoodsrehab.org). Nursery manager Valerie Slocum advises, “don’t remove newborns” as the mother will likely return. However, if a fawn is bawling, wandering aimlessly, injured, or sprawled out and covered in flies, then it needs quick intervention.

When it comes to black bears, a mother will usher her cubs up a large “sanctuary tree” to act as a babysitter, while she seeks new food sources. At times, a mischievous cub will climb down, giving the appearance of being alone, when it’s just awaiting the return of the sow.

An example of unintentional interference occurred on August 14, 2015. A bear cub was spotted up a tree in downtown Grand Marais and was soon surrounded by hundreds of fascinated onlookers. Despite the best efforts of the sheriff’s department and DNR, several capture attempts failed to wrangle in the cub for rehabilitation. The overcrowded streets made the chase very one-sided for the agile youngster. Sadly, the panicked cub retreated into Lake Superior, where it eventually succumbed to exhaustion. According to Sheriff Pat Eliasen, had people left the cub alone, it might have survived.

According to Dr. Lynn Rogers, founder and principal biologist of the North American Bear Center in Ely (bear.org), a first-year cub can probably survive on its own at seven months. Prior to that, it’s mostly reliant on its mother’s milk. A young bear entering its second year is much more independent and will be chased away as the sow resumes its breeding cycle.

Moose calves rarely leave their mother’s side. For days after birth in early May, they are unable to flee on wobbly legs, so they lay still. On the rare occasion that their mother is killed by a vehicle, for example, the calf will need assistance. Moose do not accept human food and will usually run shortly after seeing a vehicle pull over to the side of the road. They frequent the ditches in spring to eat new growth and mud laden with rich minerals.

When it comes to encountering wildlife, here are the recommended guidelines to follow:

- Keep your distance—most wildlife needs a much larger “bubble” than people.

- Don’t touch, feed or capture the animal without permission from the DNR or a wildlife rehabilitation group.

- If a panicked animal is caught in a fence or has fallen into a hole, then a quick helping hand and gentle release is okay, if it is safe to do so. Contrary to popular belief, the rescued animal will rejoin its worried parent, regardless of the human scent applied to it.

- Stay alert if you are in close contact with an animal, as critters may kick, bite, scratch or transfer ticks. Use caution.

- The best course of action in critically injured animals is to let nature take its course, or have the authorities euthanize the animal.

The Minnesota DNR pre-recorded statement is “never assume a young animal is abandoned. Its unlawful for a citizen to take a wild animal home and rehabilitate it without a rehab license or permit.” Their credo is, “If you care, leave it there.” For more info, visit: bit.ly/orphanedwildlifemndnr.

The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry states that people that find bear cubs or encounter aggressive bears should call Bear Wise (1-866-514-2327) or your local district office. For more information on dealing with sick, injured or abandoned wildlife in Ontario, visit: ontario.ca/mnrf.