Was there really a 20th century nation called Republic of Nirivia on an island in northern Lake Superior? A country with its own flag, national anthem, postage stamp, national bird (blue heron), national flower (lady slipper), and offering Nirivian citizenship to visitors?

Well, according to legends and lore of Lake Superior, yes.

In the article “The Nirivians have landed” by Mary Gordon, published in the Nipigon Gazette on October 31, 1979, it was reported that the idea for declaring the new country of Nirivia was “conceived and born” on the shores of St. Ignace Island in the autumn of 1976. As the story goes, that’s when a group of Nipigon and Thunder Bay residents, including Rusty Evans and Jim Stevens among others, concluded after their due diligence research that the St. Ignace Island Group, situated at the entrance to Nipigon Bay, had never been claimed by anyone. It wasn’t claimed by Britain in the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, signed August 9, 1849 between U.S. and British North American Colonies (became Canada in 1867), nor had it been ceded to Canada by First Nations in the Robinson-Superior Treaty signed September 7, 1850 (though territory described in the written treaty did include the North Shore of Lake Superior).

So, the Nirivians claimed the St. Ignace Island Group for the Republic of Nirivia, a name supposedly conjured up during drinks around a campfire, perhaps actually a mixed-up version of the name “Nirvana” meaning “enchanted place.”

To move the claim forward, the official national flag of Nirivia was hoisted up on October 1979 near Armour Harbour on St. Ignace Island (the largest Canadian island in Lake Superior and its Mount St. Ignace at 569 m/1,867 feet, one of Ontario’s highest points). The flag was designed by Nirivian David Kruszewski and Fawn McAllen, and described in the article as “a lone tree by day or by night, a large brooding sphinx which looks suspiciously like the volcanic islands of Nipigon Bay.” As the story goes, they also had a Nirivian Navy headed by Admiral Fish Gordon Dampier, with its one vessel, the SS Mushrush.

“We would be satisfied with something less than complete secession from Canada,” said Kruszewski in the article. “Our interest is getting control of our resources and the preservation of the islands. We propose to set up a Board of Governors to control the destiny of St. Ignace Island.” Was this real or a tongue-in-cheek kind of rhetoric? As one Nirivian explained, their intention was to “emphasize the majesty of the place rather than secede, join or revolt against anyone. Nirivia is a vision that anyone can share once they have visited.”

Regardless, the whimsical creation of the 20th century new nation caught media attention from publications like National Geographic, Globe & Mail, Lake Superior Magazine, Associated Press, Minneapolis Star and Reader’s Digest.

What really was the intent of Nirivia? Well, for starters, the visionary Nirivians wanted to establish a multi-use tourist destination where the island’s rugged beauty would be shared by all, while at the same time prevent heavy mineral extraction, preserve the resources and environmentally protect the pristine area for future generations. Rather than serious bid for a separate nation, they saw Nirivia as more a ‘state of the mind.’

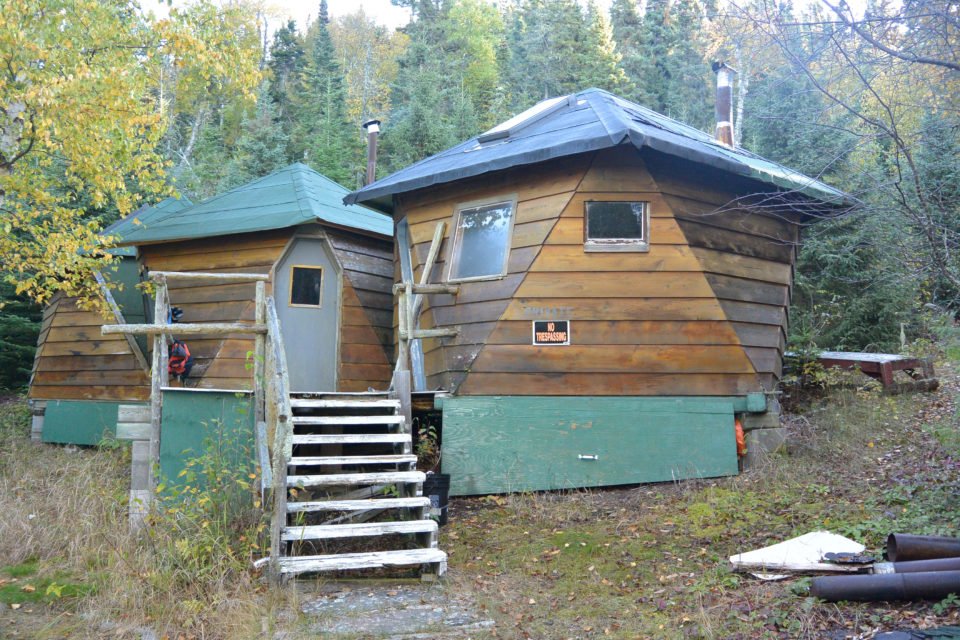

With fanciful leadership titles like King of Nirivia for Rusty Evans and Earl of Nirivia for Jim Stevens, the Nirivians built a base camp of wooden structures which included a Nirivian Embassy (actually a sauna), and a couple of geodesic-inspired cabins hidden away on the southeast side of St. Ignace Island.

So what did the Canadian government do about the declaration of the rogue republic? Apparently, the government took notice, but didn’t recognize the claim.

However, Nirivia was at risk of being destroyed in the late 1980s as its buildings were illegally constructed on Crown land without permit or license, and the Ontario government policy was dismantling of ‘squatter’ structures found on Crown land. After some negotiations, a deal was reached. As the story goes, Stevens had a mining claim on a nearby large piece of island property with high cliffs rising from the lake. So the government proposed a land swap: Stevens’ mining claim in exchange for a smaller property where Nirivia already had its buildings, plus a tourist license so it could continue operations. Stevens accepted and Nirivia was saved.

Back 40 years ago in 1979, the Nipigon Gazette wrote that the Nirivians “all agreed the land would thrive best under a national park designation for use and enjoyment by all,” but that it “needs sound management to ensure preservation of the beauty and resources.”

And today in 2019, the vision and objectives of the Nirivians are coming true with the development of the Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area (NMCA), a protected area managed by Parks Canada. NMCA extends from Bottle Point near Terrace Bay in the east to Thunder Cape at tip of Sibley Peninsula to the west and from the shoreline in the north to the Canada-U.S. border in the south. It covers an area approximately 10,880 square kilometres and more than 600 islands, including St. Ignace Island with Nirivia.

Currently under an interim management plan (2016), once legally established the NMCA will occupy approximately one-third of the Canadian side of Lake Superior, one-eighth of Lake Superior and will be the largest freshwater protected area in the world.

And Nirivia? It still exists, welcoming visitors to its enchanted site. To learn more, visit: niriviacounselling.com.