Some Indigenous art—like rock art—has been created for thousands of years, while others, like unique styles of paintings, have evolved in the last hundred years.

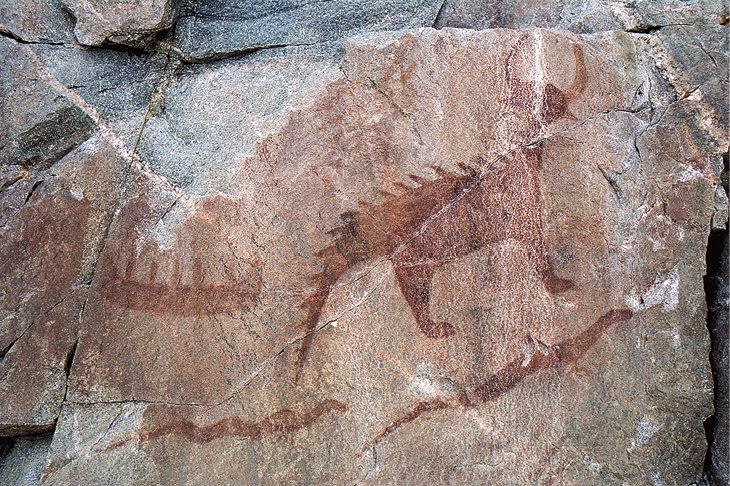

Many of us have heard about the forms of rock art known as petroglyphs, where Indigenous artists created images thousands of years ago by removing, chiselling, and/or pecking part of a rock surface (like at Minnesota’s Jeffers Petroglyphs) and pictographs where artists painted on rock surfaces with natural pigments (like Agawa Rock, Lake Superior Provincial Park). Also well-known are the Indigenous artists who have created unique paintings, like the Woodlands School of Art which started in Northwestern Ontario and gained global recognition beginning in the 1960s with Ojibwe “Legend Painters”—artists like Norval Morrisseau, Jackson Beardy, Carl Ray and Roy Thomas, the influential Anishinaabe painter with a distinctive totemic style.

One of the oldest and most complex, yet least known, Indigenous forms of art is the traditional birch-bark biting—known as mazinibaganjigan in Ojibwe—and a small number of artists in North America have been saving it from extinction.

The process for creating this art often starts with spring harvesting bark from white birch trees, carefully peeling thin pieces of the birch bark, and folding the fresh bark several times into a square, rectangle or triangle. The artist then creates an image in their mind for the art and uses eyeteeth (aka canines) to pierce the bark just enough to make indentations; to make symmetrical shapes, the artist rotates the bark in their mouth. The amazing thing about birch-bark biting is that the artist will not see the created work until the birch bark is unfolded and held to the light.

In addition to traditional birch-bark bitings as an art creation, the bitings are used in storytelling, making maps, documenting meetings, patterns for quill work, beading, basketry or hide clothing.

In North America, two Indigenous birch-bark biting artists in particular have kept it from being a lost art. Saskatchewan-born Angelique Merasty (1924-1996) of the Woodland Cree Nation of Amisk (Beaver) Lake spent a lifetime practising and producing intricate and symmetrical birch-bark biting designs; her work has been displayed in museums and art galleries including Thunder Bay Art Gallery. Through her work “bark biting has achieved status and market of a fine art” (Online Canadian Encyclopedia).

Wanesia Misquadance, a Minnesota-born and award-winning contemporary traditional birch-bark biting artist and silversmith from Fond du Lac Band of the Ojibway tribe, has brought recognition of birch-bark biting to the contemporary art world. Her creations include melding her biting designs in new materials like silver and gold.

Another Indigenous art form that predates European contact is moose tufting, where moose (sometimes caribou) hair is used to produce three-dimensional images by stitching and trimming bundles of selected hair onto tanned hides or later on canvas-reinforced velvet. Hairs are sorted by size, length and colour, cleaned, and gathered in small bundles of 15-20 hairs. Moose tufting requires precision, skill, steady hands and patience, as for example, each flower can take six to eight hours to create. Traditional dyes were roots, lichen, flowers, bark and wild berries to produce vibrant-coloured hair.

In addition to beautiful framed works of art, moose hair tufting is used on Indigenous clothing to decorate mittens, gloves and footwear. While moose tufting almost disappeared, it is making a comeback and being crafted again by artists.

Snowshoes as art? Resounding “yes!” Traditional wooden and hide snowshoes made by Indigenous people are considered art and featured throughout North America in cultural centres and museums. Snowshoeing today is primarily a recreational winter activity, however, in the past snowshoes were used for winter travel by Indigenous people.

Making snowshoes the traditional way is a multi-day process. Frames were made of wood—white ash, birch, spruce and sometimes willow—that had been steamed or water-soaked to make more pliant; and filled in webbing of rawhide strips from moose or caribou (babiche). Snowshoe laces were made from deer, caribou and moose hide and leather, and rawhide straps secured the moccasins to the snowshoes. Modern snowshoes are mass-manufactured with lightweight metal, plastic and other synthetic materials.

Dreamcatchers (asabikeshiinh in Ojibwe, meaning “little net maker”) is an art form that originated in the Anishinaabe culture. Traditionally, it is a handmade willow hoop on which is woven with string or sinew replicating a spider’s web, perhaps decorated with feathers or beads, and hung over an infant’s bed as a protective charm. Ethnographer Frances Densmore wrote in 1929 (Chippewa Customs, Minnesota Historical Society Press), the purpose of the dreamcatchers was “that they caught any harm that might be in the air as a spider’s web catches and holds whatever came in contact with it.” Dreamcatchers were not directly connected with dreams.

Dreamcatchers gained popularity among other Indigenous people in the 1960s and 1970s, and eventually became popular as First Nations crafted items.

There are many other Indigenous art forms that deserve equal recognition, like quill work (art using porcupine quills); beaded garments and the use of beads; dance, music and songs; symbolic artwork on drums; sacred birch bark records; and basketry.