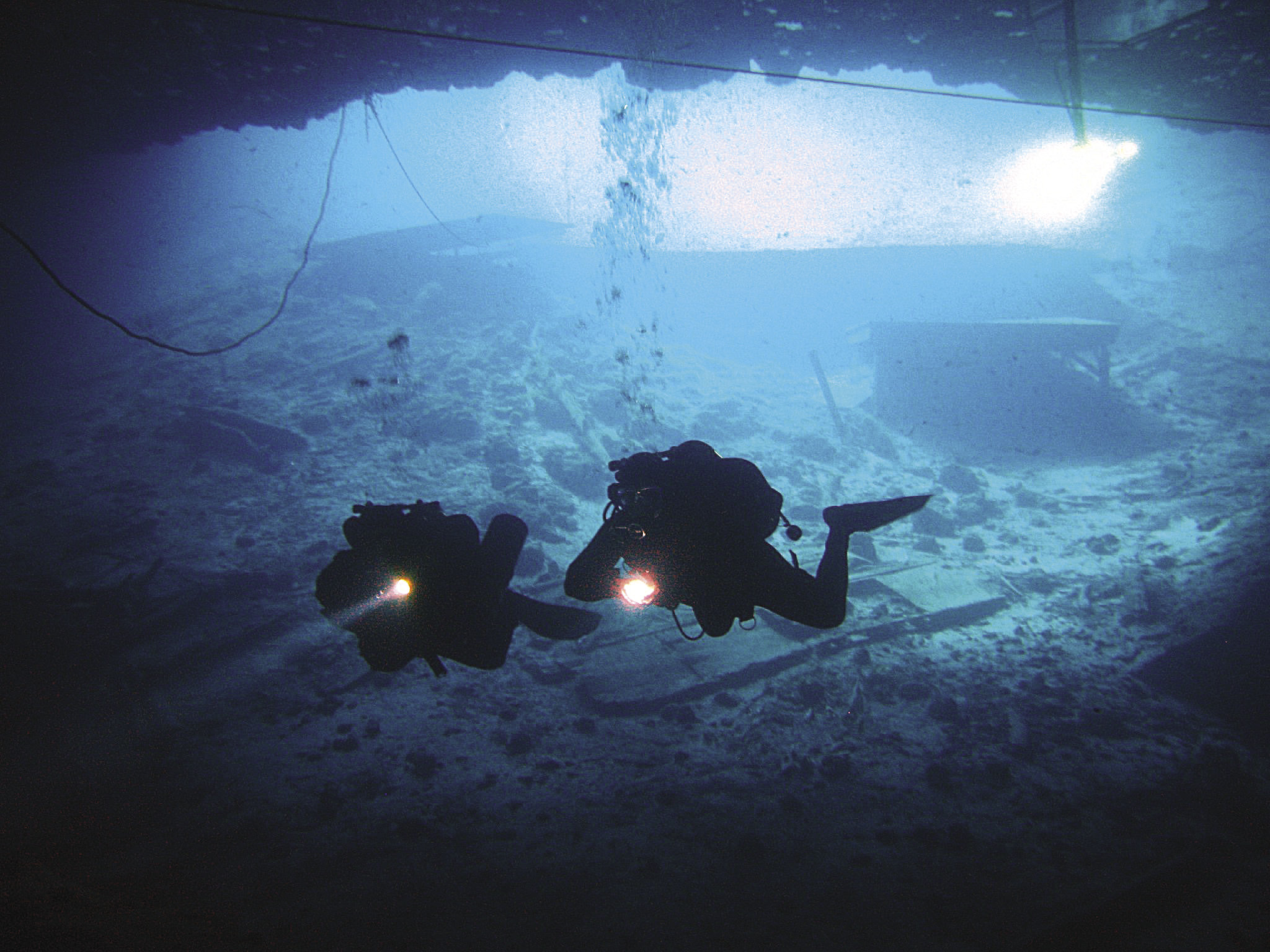

Lake Superior has become a virtual museum of maritime history. Below the aqua hue of Superior’s surface, ships rest along the bottom, preserved by the lack of oxygen and frigid water, and left for a rare few who explore the wrecks with the help of a dry suit, compressed air and knowledge of physics.

Phil Kerber has a keen interest in this underwater window into history. He has been scuba diving for 40 years and describes diving to a shipwreck like going back in time.

“It’s a time capsule,” he said. “It’s quiet, nothing around you moves. No phones. Nobody to answer to.”

Kerber is certified as a technical diver, meaning he is certified to dive down to 330 feet, which can only be done with mixed gases, such as tri-mix for a bottom mix helium, nitrogen and oxygen and nitrox for decompressing on the way up to the surface (supporting an increased amount of oxygen).

“This gives us an opportunity to dive on the deeper wrecks,” he said.

Kerber describes approaching a shipwreck like “floating in the air, from above.” As you descend, a massive hull appears and while diving you notice how the ship has stopped in time from when it sank, Kerber said. Paint is still on the ships, especially metal ones.

It is a love of the history of these ships that has spurred Kerber’s involvement in the Great Lakes Shipwreck Preservation Society (GLSPS) of which Kerber is now President. GLSPS was founded in 1996 to help preserve the underwater shipwrecks and other maritime history.

“We are the only ones in the world that do this,” Kerber said.

Kerber explained that when a shipwreck is found, GLSPS starts the process of getting the ship nominated to the national registry, which includes raising money, documentation, organizing and supporting an archaeological survey and then nominating it to the National Registry of Historical Places, which can be $3,000-$6,000.

GLSPS works to preserve the wrecks as well by doing underwater construction that holds some of the structures together, especially areas of the ships built from wood that are more prone to collapse. This keeps the shipwrecks safe for others to enjoy.

One group that benefits from this work is the Boy Scouts of America 820 Venture Crew (BSA), who have a chance to collaborate with the GLSPS on the S.P. Ely, located in a shallow bay near Two Harbors. The BSA group takes a diving course in a pool and then with the help of GLSPS and chaperones, they visit a real shipwreck in Superior. Kerber said 15 to 20 kids ages 16 to 18 get an “experience like no other.”

GLSPS is based out of the Twin Cities and has projects all over the Great Lakes, but many of these projects are on Lake Superior and Isle Royale, which is the closest to the group’s home base. Another of the group’s roles is to support what’s called PIB, or Put-It-Back. In previous decades, divers to shipwrecks would pilfer artifacts, even removing architectural pieces or in some cases, entire engines or boilers.

In the case of a ship near the Apostle Islands, a gigantic boiler was taken out of the ship and eventually laid to rest on shore. When the land where this boiler sat changed hands, GLSPS was contacted to bring out the 10,000-pound boiler and return it to its ship. Because of heaving ice, the boiler has moved away from the ship itself, and now GLSPS will move it back to the ship and chain it to underwater rock.

Another diver who can’t seem to get enough time underwater, is Ryan Hamlin, a diving instructor from Thunder Bay. Hamlin has been diving for 10 years starting with an open water certification, progressing to deeper and more technical diving certifications and now to the training it takes to teach these skills to others.

Hamlin explained that he opened Lakehead Technical Diving for people that also want to dive deep.

“It’s been a lifelong endeavor to see what’s next. What is the next wreck I have to go see?”

Thunder Bay is the resting place of several large decommissioned ships sunk on purpose so that the city could open the marina. Hamlin explained that the boats are completely untouched—in cold dark water but left exactly the way they were when they were sunk.

The Green River, for example, was a 275-foot wooden steamer that is largely still intact. It has “enormous cargo holds,” said Hamlin, and “you can go inside.” Hamlin also enjoys diving to the Puckasaw tug, which sits near the Green River off the Welcome Islands.

Hamlin’s favorite diving experience has been to the shipwreck of the SS America, a passenger and parcel ship that went up and down the North Shore from Duluth to Thunder Bay in the early 1900s. The ship sank in 1928 when it ran aground near Isle Royale. The hull of the America rests just below the surface, but the wreck sits at a fairly steep angle, Hamlin explained.

“I remember diving through the engine room and coming out the other side. There’s a piano in it. There’s a truck in the cargo hold.”

Hamlin said he enjoys diving in Superior because unlike the ocean, “you don’t have to worry about what is trying to sting you or bite you. I got bit by a turtle once,” Hamlin said. “In Lake Superior you don’t have that.”

Hamlin explained that the cold water can be mitigated with a wet suit or dry suit. The hardest part of diving, he said, is suiting up.

“After that, you are weightless,” he said.

Hamlin loves diving because it’s silent.

“The whole world has left and it’s just you,” he said. “You are looking into a window into history. You might see a boot that is still laced up, and you think ‘someone was wearing that.’ All you are thinking about is your breathing and what you are seeing … It’s very moving.”

Diving companies along Superior’s North Shore teach divers the physics of water and atmospheric pressure. Most divers start in a pool and move on to the open water from there. Many companies take divers on tours of the shipwrecks.

Hamlin assured that it’s not dangerous if you follow your training, and always plan your dive and then dive your plan. Never dive outside your training level. This will reduce your chances in becoming a statistic.

“You wouldn’t fly or drive without training,” he said. “Once you are trained, it’s not dangerous. Get in the water, get wet and find out what it is.”