In an area comprised of more forest than parking lots, using the natural and renewable resources instead of fossil fuels to heat and generate electricity makes logical sense. Biomass has been around for a long time, but only recently has the technology become more cost effective and a cleaner technology. A former coal-burning electricity plant in Thunder Bay recently converted its operation to burn biomass. In Grand Marais, the city hopes to implement a biomass heating plant. As fossil fuels become more expensive and we look at new and cleaner energy systems, biomass may become more prevalent, especially on the North Shore.

Thunder Bay Generation Station

By Julia Prinselaar

Gazing upwards, my eyes squint to make out the top of a towering concrete structure, known colloquially as “the stack.” For the last 50 years, this 193-meter appendage of the Thunder Bay Generating Station has been a staunch declaration of industry, spewing sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxide, mercury, carbon dioxide and other trace chemicals into the air.

Situated next to the Lakehead Region Conservation Authority’s Mission Island Marsh, the plant had been burning coal to generate electricity from 1963 until 2014.

In February of this year, the Thunder Bay Generating Station (TBGS) converted to use advanced biomass. The tiny wood pellets repel water and are manufactured from sawdust in Norway.

Much like the neighbouring Atikokan Generating Station west of Thunder Bay, both facilities operate on an as-needed basis to dispatch energy during times of peak demand, and to back up hydroelectric generation in low-water years and intermittent power sources like wind and solar.

Dr. Mathew Leitch, director of Lakehead University’s Wood Science and Testing Facility, says advanced biomass is the way to go. The carbon and toxic output when burning coal is greater than burning a renewable fuel.

“With coal it’s mostly the toxins, they contribute largely to greenhouse gases and of course it’s stuff that’s been stored inside the planet,” said Leitch. “Advanced biomass is much cleaner. The way that it’s produced, the way that it burns, it’s considered to be a very neutral system. You’re not really creating more carbon for the atmosphere because when we harvest the trees to create the pellets, we plant more trees that will absorb the carbon that you’ve released. Hence it’s referred to as a carbon neutral source.”

The plant’s conversion stemmed from the Ontario government’s mandate to phase out coal burning by the end of 2014, and is attracting interest from around the world. Ontario Power Generation (OPG), which operates the TBGS, sponsors the OPG BioEnergy Learning and Research Centre at Confederation College, which will include a fully functional “living lab” located within the campus’ main boiler house.

“This conversion, along with the associated research program, aligns with the City’s strategic priorities and efforts to further develop our knowledge-based economy, as well as putting the infrastructure in place to prepare for growth in the resource sector—a critical measure to advance Thunder Bay’s economic diversification,” said Thunder Bay Mayor Keith Hobbs.

The Ontario government says it will determine the long-term future of the generating station in three to five years. For now, converting the TBGS from coal to advanced biomass maintains about 60 jobs.

“Converting to advanced biomass is a positive step forward for the Northern Ontario economy. It keeps jobs at the Thunder Bay Generating Station and shows that our community and the Province of Ontario are world leaders in generating sustainable energy,” said Michael Gravelle, MPP for Thunder Bay-Superior North.

Some of the plant’s senior members said they were pleased with the facility’s conversion, and are happy to see the plant remain open.

“It’s exciting to be part of the [advanced] biomass program and creating energy from a renewable resource, a carbon-neutral source,” said Serge Bowness, thermal operating supervisor at the TBGS. “It could be like a legacy for the kids.”

Heating a City from its Own Backyard

By Erin Altemus

The “eat local” movement may soon evolve into a “heat local” movement, and Grand Marais could be a leading example of this if a city biomass project can get funding.

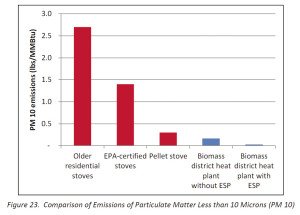

particulate matter less than

10 Microns (PM 10)

In simple terms, an industrial scale biomass heating system is just a bigger version of your average household outdoor wood boiler, except that it’s way more efficient and burns with fewer emissions. According to George Wilkes, president of the Cook County Local Energy Project (CCLEP), using biomass to provide heat on a large scale is actually quite a simple technology.

CCLEP came up with the idea about five years ago, based on successful community-scale biomass heating systems that they found in Europe. In essence, there would be a central boiler housed in a plant to be built in the Cedar Grove Business Park on the outskirts of Grand Marais. The boiler would be fed with hog fuel (any wood by-product or waste that can be used for fuel) that comes from Hedstrom’s Lumber Mill outside of town, and/or from the slash left at local and regional logging operations. The boiler would heat water piped to businesses and public facilities around Grand Marais, where heat exchangers would capture the heat from hot water and transfer that heat to each building’s own heating system (they can heat with hot water or forced air, it doesn’t matter).

Instead of trucking propane and fuel to Grand Marais from hundreds if not thousands of miles away, Grand Marais would be able to use a heat-source that comes from a by-product of the area logging industry. The end result, said CCLEP, would be millions of dollars saved in heating costs over the next few decades, fewer carbon emissions, and energy stability and independence—not to mention that this project could serve as an important model for other communities exploring biomass options.

A project of this scale is complicated, especially considering the variables involved. One of the most complicated parts, and of course the first concern that comes to the mind of taxpayers, is cost. Both CCLEP and the City of Grand Marais plan to fund this project using as little local property tax money as possible.

To date, the Grand Marais Biomass District Heating Project (as it’s formally called) has spent $715,000 to research the project, perform various analyses, develop a detailed engineering plan, secure more funding, and submit the project to the Legislature for possible funding. Of this total, $10,000 came fromthe City of Grand Marais (from the city council previous to the November 2014 elections). The rest has come from the Cook County 1 percent sales tax (80 percent of which is funded by visitors), the U.S. Forest Service, the Blandin Foundation and the state Department of Agriculture.

And then there’s the question of how much the project will cost to install and maintain. The estimate for total cost (put together in a lengthy proposal by FVB Engineering) is $14.5 million. Wilkes says that outside grant money is integral to funding the project, and the hope is to secure Legislature bonding funds to pay a portion of the project costs. Bonding funds did not come through in 2014, but the City of Grand Marais will submit the proposal again for the 2016 bonding cycle and the proposal will be much improved this time around.

The balance of the project cost would be financed by a loan, which would be obtained for one-half to two-thirds of the total cost, depending on interest rates. If interest rates were low enough (about 2 percent), the entire project could be financed. To obtain a loan like this, however, customer contracts must already be in place. Each customer must agree to purchase heat from the Grand Marais Public Utilities Commission (which will own the biomass plant) for 25 years. The customers would not need to pay anything up front to have the system installed to their building.

The only city or county tax dollars to be spent on the construction or operation of the district heating system will be those paid for heat delivered to city and county buildings, which is expected to result in significant long-term savings for taxpayers. If the biomass project is turned down by the Legislature again, there are other possible state, federal and private grants that may be looked at to fund the system.

Building a biomass facility and infrastructure is a long-term investment, but both CCLEP and newly elected Grand Marais Mayor Jay Arrowsmith Decoux believe the investment will pay off; in other words, money will be saved.

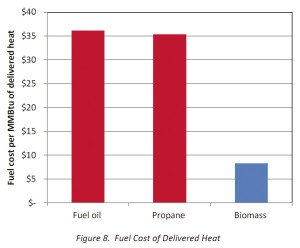

Grand Marais, unlike many locales, has no natural gas pipeline running through town. All propane and fuel oil used for heating is trucked into town. Propane has shown to be climbing steadily in cost and is prone to price fluctuations, as propane customers know who ran out of propane during the winter of 2014 when propane prices spiked. Over the last 20 years, the average fossil fuel price increase for the proposed district heating customer base has been 5.9 percent—and it’s been even more dramatic in just the past 10 years. When the customers sign the 25-year contract, they are actually locking in their heating price for the next 25 years. If fossil fuel prices continue to increase at the same rate as the last 20 years (5.9 percent), the biomass plant will save customers $10 million in heating costs—money that could then stay in the local economy.

This kind of energy independence is what got Arrowsmith Decoux behind the project. He mentioned how there is a big push for the U.S. to become energy independent.

“But domestic oil has its problems too,” he said. “We don’t have to play the oil game. I want to get off the oil train. If we have the ability to do this here, independently, we should do that.”

One thing Arrowsmith Decoux pointed out is that some critics of the idea say there is too much economic risk to invest in such a big system. “But there is risk in staying on the existing system, too,” he said.

Meaning, if the city and the businesses and public facilities all continue to invest in infrastructure to burn propane or fuel oil, and then the prices skyrocket, there is no easy way out of that either.

Instead of a fuel source that is subject to price fluctuations, biomass to fuel the plant would come from two places. First would be the waste stream out of Hedstrom’s Lumber, which is currently being transported to Thunder Bay. The plant is estimated to burn four and ahalf semi-trailer loads of biomass per week. But should Hedstrom’s go out of business or should the plantneed an additional fuel source, then slash from on-going logging operations will be sought out. This could be of benefit to logging companies who sometimes burn slash piles, or leave it to rot. Wilkes emphasized that the biomass used for fuel is a by-product.

“We are in no way competing with the timber market for prime timber,” he said.

Wilkes also noted that the system is designed to grow. The most economical growth would be for larger customers who have bigger buildings. Residentialheating from this kind of system is possible, but it’s much less economical. In fact, says Arrowsmith Decoux, this couldmake the industrial park attractive to new businesses—they wouldn’t have to invest in furnaces or hot water heaters.

Another concern about this kind of heating system, especially for those who have lived in town since the seventies, is the possible emissions from burning biomass. They may remember how the high school once heated with a notoriously smoky biomass burner. This system, Wilkes said, is much more modern. It has automatic feeding and computerized controls that means it burns at precisely the right level needed to for maximizing heat output and minimizing emissions. Additionally, multi-cyclone stack scrubbers will further reduce of particulate emissions.

“The backyard boiler is a burning barrel compared to this,” Wilkes said.

The study that CCLEP contracted with FVB Energy said that the biomass plant’s particulate emissions will be very small relative to the current background levels produced by existing sources such as residential wood stoves, vehicles, other combustion and dust.

There would be a modest amount of non-toxic ash as a by-product of burning biomass and this will have to be addressed. Hedstrom’s Lumber currently burns biomass to heat their facility and they give the ash by-product to local farmers to spread on their fields. CCLEP believes they may be able to do the same, otherwise it will need to be trucked away.

The construction of the plant would involve local contractors where possible, said Wilkes. The piping system is highly specialized and may need to involve outside contractors. Once the plant is up and running, Wilkessaid there will be 4.5 full-time equivalent jobs created—two people to procure the fuel source and 2.5 to run the plant. On the flip side, a small amount of time will be lost for propane delivery drivers, but the vast majority of the propane deliveries are residential, so it’s estimatedthis won’t have a very deep impact.

Currently 97 cents of every dollar spent on fossil fuel heat leaves the county. So instead of all that money leaving, the biomass project will keep more of ithere. In the first year, about $300,000 spent on heating costs that previously left the county would stay.

The Forest Service, DNR and state Dept. of Commerce are behind the biomass project and have written letters of support that will go with the application for bonding funds. It’s also a bi-partisan kind of project, said Wilkes. And he feels there is a lot of support for the project from the city, county and residents.

The next steps are to get all the customer contracts signed and in hand. Then the city will apply for the bonding money, which will be considered by the Legislature in the spring of 2016. If the project gets funding, the construction could start as early as fall 2016 and be online a year later.