Anyone who has spent time rambling through northern Minnesota’s forests is familiar with balsam fir. The flat needles and aromatic “Christmas tree” smell of this short-lived native conifer are distinctive. Balsam grows on a wide variety of soils and topography and is usually mixed with aspen, birch and spruce. It is a climax species that is virtually destroyed by wildfires and then takes 30-50 years to re-emerge in the stands.

Balsam fir is valuable for wildlife, serving as a major food for moose in winter and thermal cover for moose, deer, grouse and other critters when snow gets deep and nights cold. But deer and grouse rarely eat it. Dense stands also provide shade in summer. The forest products industry primarily uses balsam fir for pulp for papermaking, but larger trees are sawn into 2×4-foot studs.

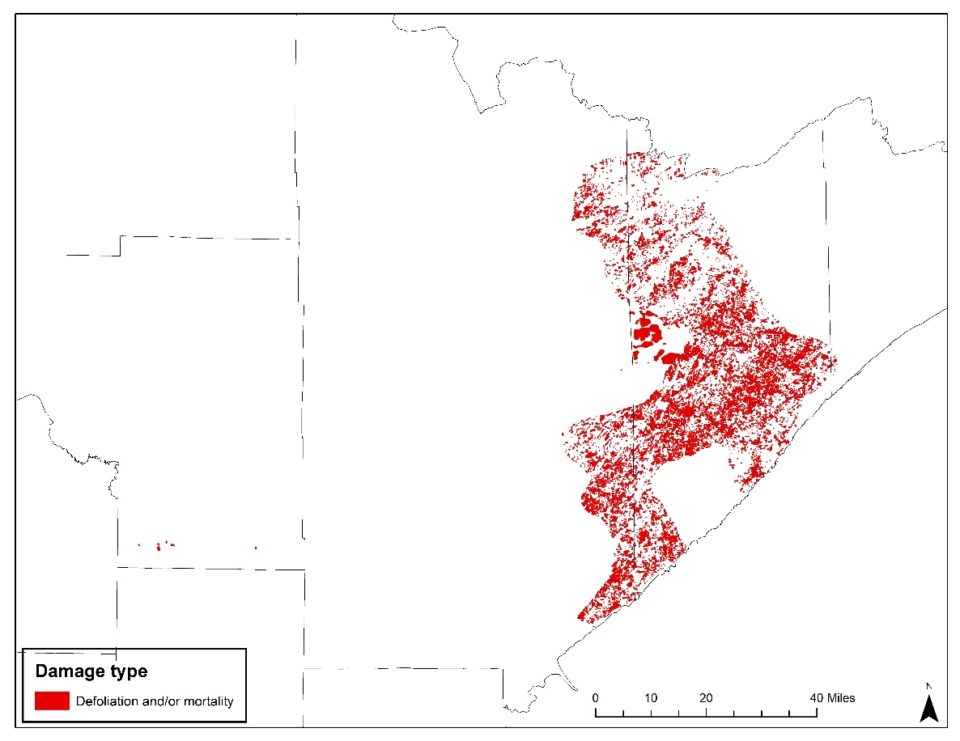

However, we can have too much of a good thing. Balsam fir is very susceptible to damage by spruce budworm—a defoliating insect larvae. The tree often dies after several years of having its needles stripped off, leaving dense patches of highly flammable standing dead trees. As one person put it, “Imagine a huge pile of dead Christmas trees being struck by lightning.” That is almost exactly what happened with the Greenwood fire this summer. We are in the midst of a large spruce budworm outbreak which impacted 345,997 acres in 2020—right where the fire began. Fire suppression in spruce budworm-killed stands is extremely difficult, resulting in explosive fire behavior which transports large amounts of peeling bark, fine twigs, and branchlets in convection columns which start spot fires downwind.

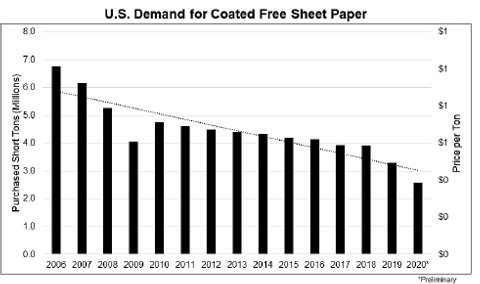

Our ability to manage balsam fir to prevent the insect outbreaks and subsequent fires is predicated on having markets to sell the wood. Up until 2020 we were able to utilize virtually all balsam fir cut in the state. But the societal changes brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the demise of the biggest consumer of this fiber. Verso Corporation in Duluth manufactured coated paper—the kind often used for newspaper inserts and flyers. They consumed over 50 percent of the balsam fir in the state and nearly all of the balsam generated in the far northeast portion of the state. Unfortunately, the pandemic dramatically decreased demand for Verso’s product, forcing them to close the Minnesota mill and another in Wisconsin. Yes, there are other markets, but the transportation costs from remote areas prohibit full utilization of the resource.

This situation creates many problems for loggers and land managers. Balsam fir is present on nearly every timber sale in northern Minnesota. The land managers have timber sale prescriptions and utilization standards that dictate what species get cut and limit waste of the resource. They want the balsam cut during timber harvests, regardless of market conditions. So, loggers are forced to burn fuel and incur manpower costs to cut down something they can’t sell. This is contributing to a large number of timber permits containing balsam fir going unsold. For example, in the DNR Two Harbors Area 77.8 percent of the timber sales went unsold in fiscal year 2021. That figure was 33.1 percent in FY20 and 26.1 percent in FY19. Those unsold stands will continue to get older, less healthy and more fire-prone every year until they are managed.

Some land managers are getting creative by pricing these sales low enough to offset the transportation costs, by relaxing utilization standards so the balsam can be left to be burned, or by making it optional to harvest. The latter means balsam fir is left standing in place, which is not desirable either. Balsam is shade-tolerant, and its shade can prevent the growth of a new forest around it. Quite the dilemma.

All of this proves that the Economics 101 laws of supply and demand reach all the way into natural resources management. Without markets for finished products, we lose the ability to manage our forests for a vast array of ecological, social and economic values. And in this case, it can quite literally put our homes, lives and livelihoods in jeopardy. We ask that you keep this in mind and defend the forest products industry when you hear misinformation about timber management in Minnesota. We are a vital industry providing good paying jobs in rural areas for over 34,000 people, all while serving as the tool to keep our forests and wildlife healthy and thriving.—Rick Horton, VP of Forest Policy with Minnesota Forest Industries