Did you know thousands of dried carcasses of lake sturgeon were once stacked like firewood and used as logs for fuel on steamships?

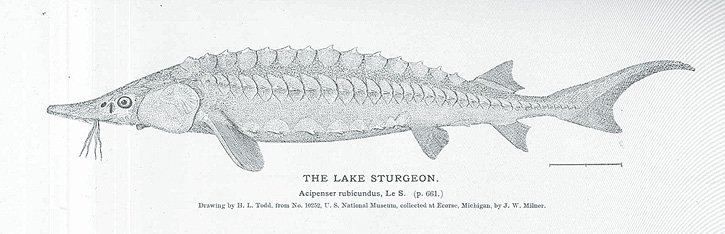

The first time I saw a lake sturgeon was in the large observation tank lining the tunnel-like stairway that descended to the Kay-Nah-Chi-Wan-Nung Centre on Rainy River near Emo, Ontario. Not the prettiest of fish, the sturgeon really does look like a large pre-historic relic. Its long torpedo-shaped body is armored with five rows of large bony-like plates called scutes and it has a shark-like tail and a sucker-like mouth located under its head. Scaleless and toothless, the lake sturgeon has a flattened snout with four barbels (whiskers). Typically, lake sturgeon can grow to 7 to 12 feet (2 to 3.5 m) in length, weigh more than 300 pounds and can live to around 150 years. While fierce-looking, scientists say they are considered docile, shy and some say playful as they do leap out of water like dolphins.

A direct ancestor of a family of fish going back 250 million years to the Triassic Period, the appearance of today’s lake sturgeon remains virtually unchanged since 150 million years, giving credence to being called a ‘living fossil.’ Imagine—its ancestors were swimming in waters at the same time as dinosaurs walked on earth. Some people call today’s sturgeon the “Dinosaurs of the Great Lakes.”

To Indigenous people, the lake sturgeon (namao in Cree) became culturally significant. For thousands of years—even before the pyramids were built—large groups of Indigenous people gathered at places like Kay-Nah-Chi-Wan-Nung to harvest the sturgeon during spawning, feast, meet socially, renew friendships, trade and hold traditional ceremonies.

Every bit of the sturgeon was used by Indigenous people. It provided fresh meat and when dried, meat similar to pemmican that could be kept for years. Bones were used for needles, spearheads and arrowheads; isinglass from dried swim bladders to make paint and glue for teepees; oil for medicinal purposes; bags and containers made of the fish skin; and the stomach lining for drum covering. So important was the lake sturgeon to the Indigenous people that they called it “Buffalo of the Water.”

Initially, early 19th century European settlers ate dried sturgeon they had traded from Indigenous people. At the time, there are stories the lake sturgeon were so numerous they could capsize a boat during spring spawning season.

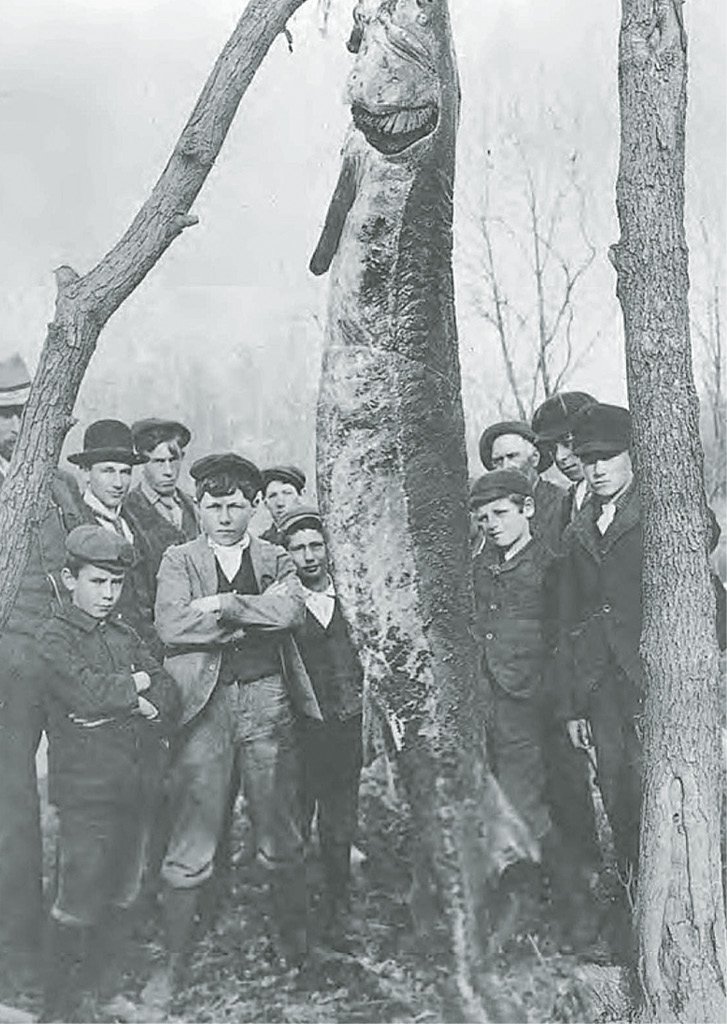

However, once commercial fishing began, the lake sturgeon was considered a nuisance, a ‘trash fish’ by the fishermen because the sturgeon’s barbels and bony plates ripped and destroyed their nets set for fish like lake trout, herring and whitefish. “And so commercial fisherman just slaughtered them,” said environmental historian Dr. Nancy Langston in her 2019 Mandel Lectures in the Humanities presentation “Welcoming Back Namao: Indigenous Communities and Restoration of the Great Lakes Sturgeon.” Dr. Langston is the Distinguished Professor of Environmental History at Michigan Technological University and in spring 2020, she was the Fulbright Canada Research Chair for Interdisciplinary Sustainability Solutions at Thunder Bay’s Lakehead University.

Many thousands of lake sturgeon were killed by commercial fishermen and the dead fish stacked to dry on the banks of rivers and lakes. The oily dried carcasses were loaded onto steamships to be used for fuel.

Then, in the 1860s, commercial fishermen began harvesting lake sturgeon after finding new uses. The previously-scorned sturgeon became a huge commercially valuable resource, prized for its smoked meat, swim bladders processed into isinglass (used in beer/wine making), sturgeon hide, and roe (eggs) shipped overseas for caviar by both the U.S. and Canada.

According to the Michigan Sea Grant (MSG), in 1880, more than 4 million pounds of sturgeon were taken from Lake Huron and Lake St. Clair to be processed in Michigan. By the 20th century, a combination of things like overfishing, pollution, construction of dams (blocking spawning areas), habitat change and environmental challenges led to a drastic drop in sturgeon catch and fisheries closed. MSG reports that in 1928 the total harvest of sturgeon from all of the Great Lakes fell to less than 2,000 pounds.

While the lake sturgeon is still threatened or endangered in places, the “Buffalo of the Water” is slowing coming back. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources reports lake sturgeon exist in Lake Superior, Lake of the Woods, and many rivers, including the Rainy (with 100,000 sturgeon 40 inches or longer), St. Croix, St. Louis, Kettle and Red River.

Referring to lake sturgeon as “really amazing,” Dr. Langston likened the sturgeon to zombies, “because they’re never quite dead. They keep returning.”