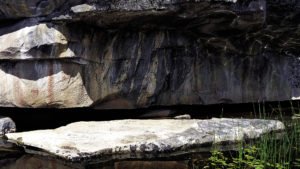

At the turn of the 20th century, an eccentric hermit named James Alexander “Jimmy” McQuat built this log home on the shore of White Otter Lake, south of Ignace, Ontario. The story goes that he single-handedly constructed this enigmatic mansion from red pine logs that he felled, hauled and interlocked. Just a few years later, he drowned nearby. White Otter Castle has now been restored through local efforts and is without road access, but sees a number of visitors each year by motor boat, canoe and snow machine. |JULIA PRINSELAAR

White Otter Castle and Beyond

This July, Canada marks 150 years since its British colonies unified to form a single country. But long before confederation, and the railroads and highways that followed, the original pathways of the land were connected by water—from the St. Lawrence Seaway into the Great Lakes Basin; across the northern prairie provinces, reaching high into the Arctic. From watershed to watershed, travel and commerce into uncharted wilderness was made possible with one of the oldest modes of transportation in existence: the canoe.

Across the abundance of freshwater lakes and tributaries in Canada, there have been countless journeys by canoe. Each of them has held its own purpose and meaning. Joseph Boyden’s bestselling novel, Three Day Road, chronicles the voyage of a wounded Cree soldier, guided by his aunt who paddles them back home to the far north of Ontario.

Some of today’s more adventurous Canadians pay homage to our heritage by paddling across the entire country. Atikokan-born Mike Ranta and his dog Spitzii are currently on their fourth such expedition, this time to commemorate Canada’s 150th anniversary.

When I think about what water means to me, and my connection with place, I think of one particular journey. It wasn’t a summer-long expedition, but a nine-day, point-to-point route through Turtle River Provincial Park, northwest of Quetico and the Boundary Waters.

Stepping foot in White Otter Castle, a legendary landmark accessible in the summer by boat or float plane only, was on my Northern Ontario bucket list. So on the morning of July 23, 2016, my paddling partner and I launched our Alumacraft canoe from the glassy waters of Clearwater Lake, located about 35 miles northwest of Atikokan. We headed for the Castle, and continued to follow a 90-mile counter-clockwise loop through several lakes that swelled and tapered along the Turtle River.

We faced our share of challenges from the beginning. We got lost (briefly) within the first couple of hours after paddling a small corner of our route without a map, and mistaking the wrong inlet for our first set of portages. (We like to wing it sometimes.) We packed a blanket but no sleeping bags—an oversight that forced us to sleep in all of our clothes, including rain gear and a crinkly emergency blanket. Did I mention we like to wing it sometimes? Well, this is not a great example.

But trials like these were far outweighed by the gains we made as a team. Free from the stresses of day-to-day life, the wilderness led us to work together. We rarely needed words to set up and tear down camp, or orchestrate 17 or so portages (we lost count after that). As with most challenges, these were means for bonding, entertaining post-trip stories, and the reassurance that together, we were stronger.

The calm waters of the Turtle River made for easy paddling and nice tans. We hoped to spot a moose, but only found a set of old tracks along a cold spring that fed into the river. How refreshing it was to taste ice-cold water for the first time in nearly a week!