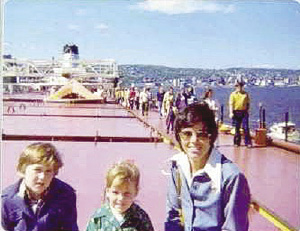

When I was nine, my family climbed onto the deck of the M/V Roger Blough. During a rare open house in Duluth, we saw first-hand that lake freighters are huge. Vessels that only travel the Great Lakes are traditionally called “lakers” or boats, even though they’re technically ships. The Roger Blough first sailed in 1972, so when I stepped on board in 1976, it was relatively new. At 858 feet long, the boat has been stuck in my mind ever since. My family lives in Duluth now. Sometimes I see the Roger Blough floating by and it makes me smile.

When I looked into ore boats, I learned they’re connected to everything else. Shipping is connected to iron mines, railroads, ore docks, the Soo Locks and steel mills. As a curious amateur, it was hard for me to focus on just the ore boat piece of this network. Three things surprised me. First, the earliest shipments of ore happened from places I didn’t expect in interesting vessels. Second, the scale of ore shipping today is bigger than I thought. And third, ore shipping has a massive impact on our economy.

Thanks to Laura Jacobs at the University of Wisconsin-Superior (UWS), I was able to explore the university’s Lake Superior Maritime Collection. With her help, I was able to zero in on the first ore boats. Iron ore was discovered near Marquette, Michigan in 1844. One source from UWS said a test batch of Marquette Range ore was sent to Pennsylvania steel mills in 1850. There were only a couple of small steamers and just a few schooners on Lake Superior at that time.

Then, two sources pointed to a “six barrel” shipment from Marquette in July 7, 1852 on the steamer Baltimore. This small consignment to Detroit was the first commercial shipment of iron ore on the Great Lakes. According to a brief history published in the 1910 Annual Report of the Lake Carriers’ Association (LCA), the first ore shipped “in any quantity” on Lake Superior happened in September, 1853. Four unnamed vessels took those 152 tons from Marquette to Sault St. Marie (“the Soo”) where they were portaged around the rapids and shipped to steel mills in Pennsylvania.

Then the LCA report says the steamers Samuel Ward, Napoleon, and Peninsula shipped ore from Marquette in 1854. Supposedly, Mr. McKnight and his horse carted every pound of freight around the rapids at the Soo that year. Construction of locks on the St. Mary’s River connecting Lake Superior to Lake Huron began in 1852. The Soo Locks were finished in 1855 and McKnight’s horse was probably happy about that. The brig Columbia was the first craft to carry Marquette Range ore through the new lock on August 17, 1855 when it took 132 tons to Cleveland.

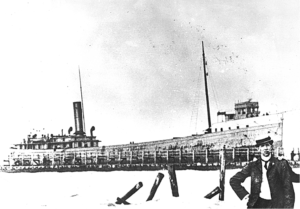

Then ore was mined from the Vermilion Range in Minnesota and shipped by railroad to Two Harbors. The steamer Hecla and the Ironton carried the first ore from there on August 1, 1884. The Ironton was a schooner used as a consort barge, towed by steamships. Then, the Mesabi Range opened up near Mountain Iron, Minnesota. Barge 102, a “whaleback” designed and built in Duluth by Alexander McDougall, carried the first Mesabi Range ore from the Allouez dock in Superior, Wisconsin on November 11, 1892.

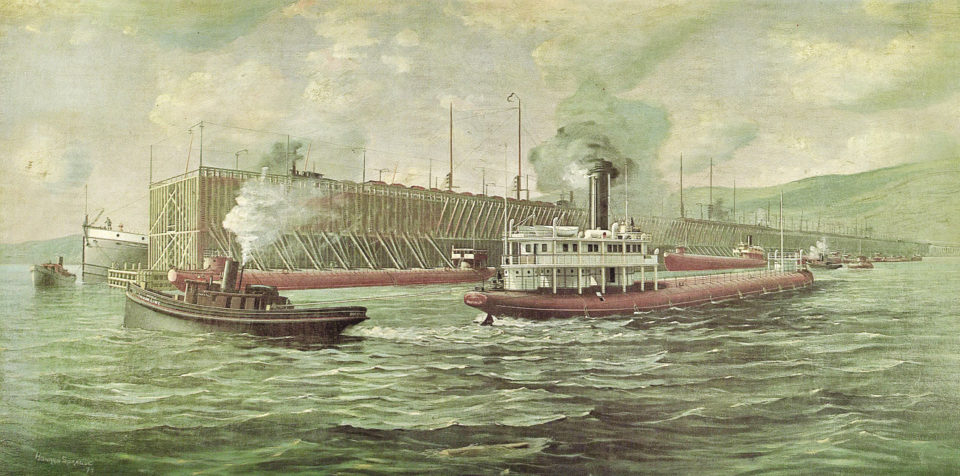

On July 22, 1893, a brand-new dock on the Duluth side of the harbor got its first Mesabi Range ore. I couldn’t find the name of the boats that carried that first trainload. But there’s a wonderful painting by Howard Sprague. It depicts that Duluth ore dock bustling with barges and steamships, both with the whaleback design. Go see the last surviving whaleback freighter, the SS Meteor, on Barker’s Island in Superior.

That 1910 LCA article mentioned that iron ore became the largest percentage of freight on the Great Lakes in 1888. This brings me to my second surprise: the scale of ore shipping today. Several years ago, I saw the M/V Paul R. Tregurtha, the largest boat on the lakes at 1013 feet long, sail out of the Duluth Harbor loaded with coal. Ever since, I mistakenly thought that, since the biggest laker carried it, coal must be a bigger deal than iron ore.

I spoke with Deb DeLuca, executive director of the Duluth Seaway Port Authority, and she quickly corrected me. “In 2019, 59 percent of the 35 million short tons of bulk cargo that was shipped from the Twin Ports was iron ore. That’s over 19 million short tons of ore,” DeLuca said. “The next largest categories were coal at 24 percent, limestone at 10 percent, and grain at 4 percent.” The Port of Duluth-Superior is the largest freshwater port in the world and the Bureau of Transportation Statistics ranked it as number 20 in all American ports by tonnage. Iron is still the champion at one of the busiest ports in the United States.

My third surprise was how much those ore shipments impact the rest of our economy. DeLuca pointed me to a study about the Soo Locks that was written by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). While I read it, I kept wondering, ‘Why are they so focused on Lake Superior iron mines?’ Somehow, until I read this 2015 report, I didn’t realize there aren’t any other U.S. iron mines. There’s one mine left near Marquette and several on the Mesabi Range in Minnesota. That’s it. DeLuca told me that “roughly 80 percent of the iron ore shipped from Duluth-Superior goes to U.S. ‘first pour’ steel.”

Since most of the integrated steel mills in the U.S. are reached via the lower Great Lakes, the Soo Locks are incredibly important. The biggest modification to the locks was the construction of the Poe lock in 1896 and the expansion of that lock from 800 feet to 1200 feet in length in 1968. That led to the building of the 13 lake freighters that are each at least 1,000 feet long. They all continue to work today. A single One Thousand Footer can carry 70,000 short tons of iron ore. That’s seven trains with 100 rail cars each or 3,000 trucks. The iron ore in a single One-Thousand-Footer is worth about $4 million. The DHS report estimated the value generated by one ton of that ore at $23,800. That means just one laker has an economic impact of $1.7 billion. That’s billion with a B.

It’s amazing that such a massive vessel can be run by just a few people. Chrissy Kadleck, Public Relations for The Interlake Steamship Company, taught me about the crews. Kadleck said, “Our crews generally range in size from 22-25 per ship. On the deck side, we have a captain, mates (first, second and third), several deckhands. On the engine side, we have a chief engineer, and three assistant engineers (first, second and third), and a few additional unlicensed positions.”

The harsh winter weather and lake ice limit navigation on the Great Lakes. The Soo Locks typically close from approximately January 15 until March 25 each year. That leaves just under a 10-month shipping season. Crews spend a lot of that time away from home. “On the licensed side (the captain and mates, chief engineer and assistant engineers), our crewmembers work 60 days on and 30 days off,” said Kadleck.

The Interlake Steamship Company is building a brand new laker, named after the company’s president. Construction is underway in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin. Kadleck said, “Engineering on the M/V Mark W. Barker is progressing well at Fincantieri Bay Shipbuilding with module fabrication, hull structure, accommodation house structure and engine control room on schedule. The ship is expected to sail in Spring 2022.” This is a milestone event since that will make around 40 years since a fleet added a new laker. “Our M/V Paul R. Tregurtha, originally launched as the M/V William J. DeLancey, was the last ship built for our fleet and she sailed in 1981,” said Kadleck. This new vessel will be 639 feet long and 78 feet wide and will be able to pass through the Welland Canal. This ship will be versatile because it’s able to sail the entire St. Lawrence Seaway as well as the Soo Locks.

I’ve only dipped my toe in the Lake Superior water when it comes to this topic. Because I visited the Roger Blough as a kid, I thought I was smart about lakers. Because I live in Duluth and see them all the time, I thought I knew about shipping. Turns out, I was no smarter than somebody who’s never seen Gitche Gumee and only knows the Edmund Fitzgerald song. Now I know ore boat history on the Great Lakes is richer, larger in scale, and has a broader impact than I realized. Ore boats are sailing into the 21st century and will soon be joined by a brand-new U.S.-built laker. Like the first lyrics in Gordon Lightfoot’s song, “The legend lives on…”