The north side home of Melanie Luc and her family is not noticeably different from many a Thunder Bay dwelling—unless, that is, you happen to visit during the summer and see enclosure after enclosure of chrysalises waiting to hatch into adult monarch butterflies. Seeing a fully-grown butterfly emerge from a chrysalis is a magical experience, but it is also part of a great deal of human assistance by Luc, beginning with the deliberate planting of milkweed in her front and back yards. Every early summer, millions of monarch butterflies migrate northward from Mexico. Thunder Bay is but one of countless stops along the way to feed, breed and for the females, to lay eggs.

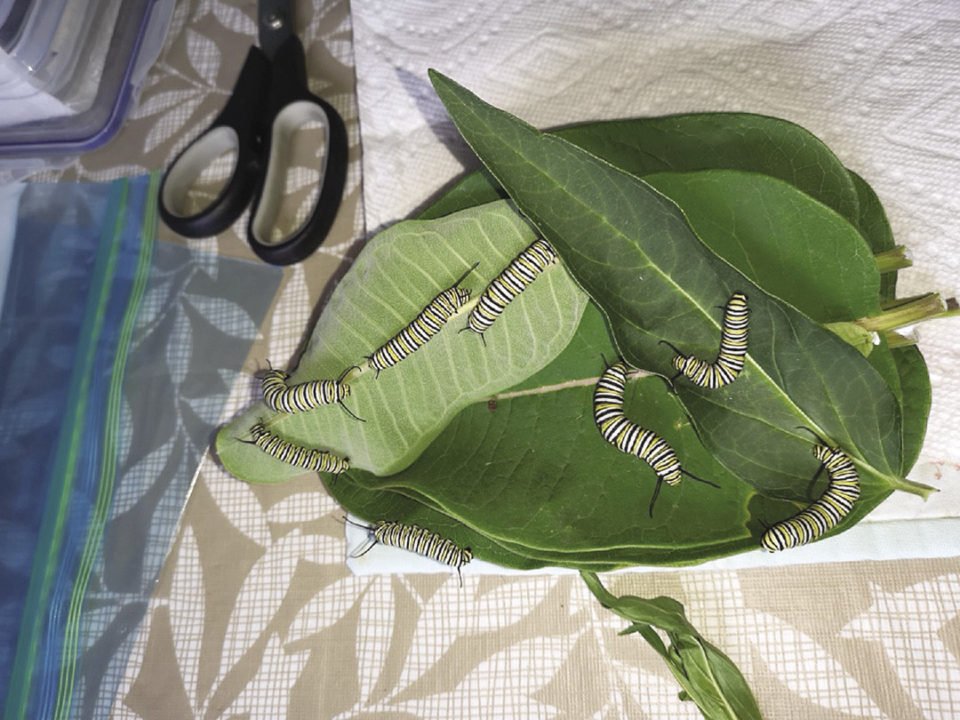

“Once the monarchs hatch,” Luc explains, “they go into reproductive mode and lay more eggs, and so it goes.” Luc carefully collects eggs and provides milkweed leaves—the exclusive diet of monarch caterpillars—for the voracious young to feed on as they prepare to become chrysalises.

“From chrysalis to adult monarch takes about two weeks,” she adds. “I bring the eggs inside where they can hatch in safety.”

The monarch is a unique insect in that it is toxic, or at least very irritating to any predator that tries to eat one. Ironically, this is both a blessing and a curse: Though adult monarchs feed off different flowering plants, they have evolved to depend solely for their toxicity on milkweed, a plant threatened by herbicides, urbanization and the cultivation of cash crops. In Mexico, to where the monarchs migrate beginning in late October, the forests of pine and oyamel trees on which the butterflies cluster and winter have been under attack by commercial logging and farming interests. In other words, the butterflies are threatened by habitat destruction on both ends of their journey. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the monarch population has been diminished by some 90 percent since 1990. Extinction is not an impossibility.

For Luc, the monarch is both a choice and a symbol.

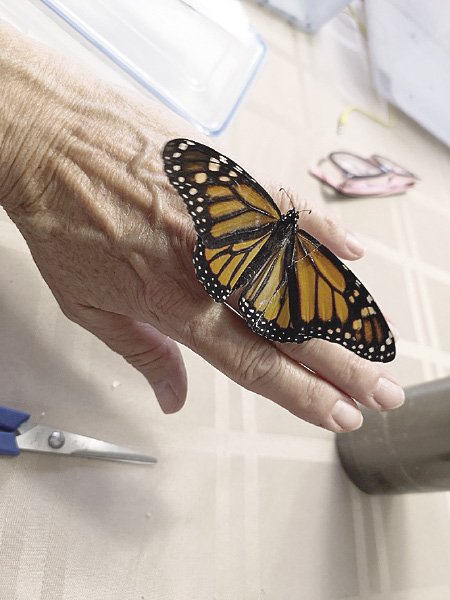

“Thirteen years ago, I was going through breast cancer treatments,” she says. At one point, when she was at a very low ebb, she had a profound spiritual experience involving butterflies. At a later visit with a friend to a nursery, Luc bought a milkweed plant, which turned out to have monarch eggs on it—and so began Luc’s work with the threatened butterflies.

“The chemo(therapy) makes changes in your body,” she reflects. “It’s like I was given a second chance at life, becoming a new me, like these caterpillars become butterflies.”

After the first year as she watched, fascinated, the progress of the insects from egg to mature adult, Luc began bringing the eggs inside to protect the caterpillars from insect predators and to help propagate the butterflies. In that supportive environment, the monarchs thrived, and Luc’s summer became a never-ending chain of work:

“(The caterpillars) devour the leaves very quickly, the bigger they get,” she says. “and you cannot let them run out, so it becomes a full-time job, but a worthwhile, rewarding one. I usually have a 90 percent success rate, where out in the wild they only have 10 percent.”

Fortunately, the milkweed plants continue producing leaves right up to the frost season, so there is plenty for the caterpillars to eat. By November, Luc’s butterflies have all started their migration to Mexico, an epic journey of thousands of kilometres.

“The early hatchers reproduce,” she says. “The later ones don’t mature sexually, but save their energy for the migration.”

These late hatchers will live for eight months, while the usual summer life span is three to four weeks.

“Once they have overwintered in Mexico and the daylight increases, then they will start to reproduce,” she says. “They start their migration back to their summer homes, reproducing along the way. I never see the same butterflies return once released. The ones coming north are four generations later.”

Even with all the protection Luc gives her charges, accidents will happen. Two years ago, a female released in Luc’s garden lost most of her wing on one side, and was unable to fly.

“I had watched some videos on Youtube of repairing broken wings,” she says. “Since I did save some wings from a dead butterfly just for this purpose, my daughter and I decided to see if we could help her.”

Some contact cement, baby powder and deft work with a cutting knife, and the young female was able to fly aloft with the aid of the wing of a deceased male.

Luc recognizes that she is part of a small army of monarch helpers, a number of whom live in the Thunder Bay area.

“I haven’t kept track of the numbers that I have raised,” Luc reflects, “but it has steadily gone up in the last 13 years. Last year was a stellar year for everyone that I spoke to, and I alone released over 450.”