Back in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Lake Superior was a popular cruising area for the wealthy owners of luxury steam yachts. Here’s a snapshot look at two of those yachts that toured northern Lake Superior and met different fates.

During the summer of 1897, the luxury steam yacht Gunilda (which later became a famous Lake Superior shipwreck) was being built in Leith, Scotland, at a cost of $200,000 (equivalent of $7.6 million in 2025). That same summer of 1897, the story of another luxury steam yacht was unfolding on Lake Superior, which eerily mirrored the eventual fate almost 14 years later of the Gunilda in the lake’s same general area.

It was July 31, 1897, when the 172-foot-long steam yacht Comanche steamed out of Cleveland, headed for a cruise on Lake Superior. Onboard was one of America’s most famous and wealthiest men, Senator Mark Hanna. Built in 1892 at the Globe Iron Works Company of Cleveland, the New York Times called her “one of the most luxurious yachts afloat.”

The registered owner was multi-millionaire Howard M. Hanna, however, Comanche was often used—as it was on this particular July in 1897—by his older brother Senator Mark Hanna. In addition to the Senator and his family, there were seven guests on the cruise, including the ex-Governor of Minnesota, William R. Merriam and his wife Laura, and a crew of 18.

Comanche began her journey in August 1897 through the Nipigon Strait in northwest Lake Superior, an area one newspaper called “the most dangerous passageways on upper lakes.” Some newspaper reports wrote the captain himself was piloting the yacht, while other reports indicated a pilot had been hired to navigate the waters. Waters were calm around midnight when Comanche entered the strait. Hanna and the passengers had already settled down for the night.

Then, without warning, the yacht lurched violently, shaking from stem to stern. It rocked and shifted a bit before she stopped and lay still.

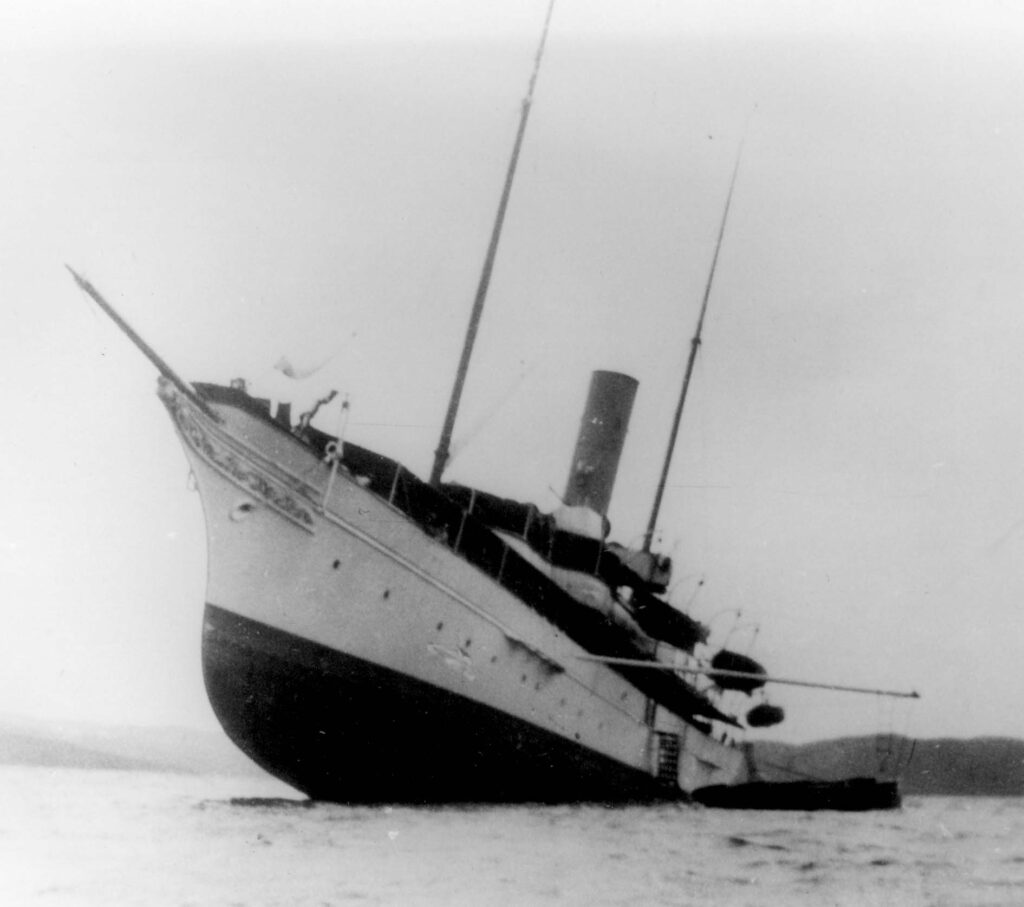

Much confusion and panic ensued on the yacht, as passengers scrambled out of bed to put on life preservers and prepared to evacuate. The captain and crew took soundings that confirmed water was rushing into the yacht’s hold, but not enough to sink the boat. The captain determined the yacht was not in a “serious position,” and there was no need to evacuate. Comanche had rammed into a rock formation and was now precariously perched on the rock, her stern still in deep water. She was stranded but safe on the rock, unless there was a storm.

In those days, there were no radio communications on ships. A crew member went ashore by boat to the Nipigon station on the Canadian Pacific Railway to send a dispatch to Port Arthur (now part of Thunder Bay) calling for two tugs and a lighter.

For the next 16 hours, the Comanche was stuck on the rock with her passengers and crew aboard. Their situation made headlines throughout North America: “Hanna’s Yacht was Stranded, the Comanche Runs Aground on Clay Bank in Lake Superior: Senator and Guests Had What They Termed a Very Close Call.” “The Party had a narrow escape.” “Senator Hanna in peril.” New York Times (August 13, 1897) told readers, “Senator Hanna and the party of pleasure-seekers accompanying him on a cruise of the Great Lakes had a thrilling experience today on the wild northern coast of Lake Superior.”

Two tugs arrived in the morning, made repairs to the ship’s plates in three hours, and at 4 p.m., the tugs pulled the Comanche from the rock and safely back in the water. After a small leak on the yacht was deemed harmless, the Comanche continued on her voyage to Cleveland, accompanied by one tug.

“We are all right but had a very close call,” Hanna told the world.

So where did Comanche end up later on? Well, less than a year after the rescue in the Nipigon Strait, Comanche was purchased by the U.S. Navy on May 28, 1898, commissioned as USS Frolic and put in service patrolling off the Philippines and China. In 1909, she was transferred to the U.S. War Department, renamed El Aguila (The Eagle) and served as a dispatch boat in the Philippines. And in 1923 she was sold to Chinese merchant Chau Chiaco for use as his private gunboat on China’s Yantze River.

And what about the 196-foot luxury steam yacht Gunilda? Well, 14 years later after the Comanche incident, Gunilda was cruising northern Lake Superior in August 1911. Onboard was its owner, U.S. multi-millionaire William L. Harkness, and his family and friends. Gunilda entered the waters of the Schreiber Channel in the lake’s Inner Passage when she ran aground hard on submerged rock, now known as McGarvey’s Shoal (actually the peak of an underwater mountain). Passengers were evacuated and salvage tugs called to release the yacht from its precarious position.

But things didn’t work out that way. Refusing to wait for the assistance of a second tug, Harkness demanded the lone tug James Whalen (which had already reached the site) to do the job without delay. The tug did release Gunilda, but she then rolled over to starboard, filled with water, and sank down 270 feet (82 m) to the lake’s bottom. The Gunilda shipwreck wasn’t discovered until 1967.