THUNDER BAY—Every Mother’s Day for the last four years, Olivia Pelletier celebrates by grabbing a garbage bag and hiking Anemki Wajiw (also known as Mount McKay in English) with her family. As the family walks along, picking up garbage of to-go coffee cups, plastic pop bottles, and old chip bags, they are affirming their relationship to Mother Earth.

“Every walk, I explain that the trees are living, breathing, feeling, eating and sleeping. Every year we talk about all the gifts Mother Earth gives us, from shelter, to food, to medicine; how Mother Earth has cared for her children and we need to love and care for her right back,” says Pelletier.

He’s free-spirited, a pow-wow dancer that danced for A Tribe Called Red, and a member of the Sugarbush collective that tap the sugar maples found on Anemki Wajiw and make maple syrup. His name is Ethan—he is six years old and is Pelletier’s firstborn.

“I want to raise my kids to be proud of who they are and I need them to know that to live a balanced life, we need to connect with the land, and get back to our roots. It’s good for our health; physical, mental, emotional and spiritual,” says Pelletier.

Every year, the relationship between Pelletier’s children and the earth grows stronger and stronger and they are showing their love while fulfilling their responsibility as the original stewards to the land.

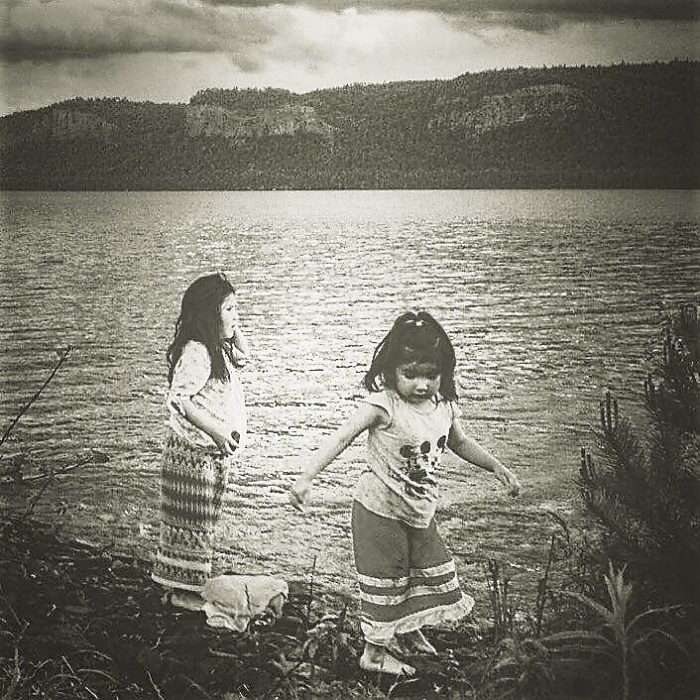

The Anishinaabeg, Ojibwe people, have always been stewards to the land, in contrast to the colonial philosophy believing in land ownership. The Anishinaabeg know that earth gives life and one day we will go back to the earth and the cycle will continue. Indigenous moms plant their children’s feet in the ground from birth to introduce them to Mother Earth. Helen Pelletier, Olivia’s aunt, says one of the biggest differences for Anishinaabe moms, is that we will let our children play in the earth, uncover worms while gardening, and run through the grass barefoot. The relationship with Mother Earth is important.

Shy-Anne Hovorka, a musician and an educator, was raised in a few different foster homes growing up before being adopted by her family. When she started her own family, it was very important that her son, Rex, have a good understanding of where he comes from. He’s only three years old and he’s already been gifted a dream catcher, medicine pouch and smudge bowl, an eagle feather, and regalia.

Hovorka and her husband make it a point to leave as little a footprint as they can on the earth. They grow, hunt, trap, or fish almost all the food they eat. Rex also has his own little garden that he cares for, but out on the land is where everything they talk about is really solidified. The winter months are a favourite time of year for Rex because it’s the one time of year that he can walk anywhere. The lakes and streams are frozen over and he can get anywhere he wants.

“When we’re out on the land, I show him that everything has life; the trees, the water, the fish, and everything has a job to do, from the rocks that get heated by the sun, that helps to melt the snow, that uncovers the earth, that exposes the insects,” says Hovorka. In Anishinaabe culture, everything is relational, including rocks. Rocks are used in ceremony because they hold the spirit of our ancestors. It’s one cycle of life and we are all interconnected and dependent on Mother Earth.

Mary Magicskin was raised in the City of Thunder Bay but her grandparents took her, her siblings, and all her cousins camping every summer. It was there that they lived off the land and received teachings from their grandparents. They learned lessons like we are all connected to one another and to the earth and that everything one needs to survive can be found on the land. Spiritual teachings like cutting your hair or the strawberry moon were done in private so she knew it was sacred and special. Of course, Anishinaabe spirituality was not as accepted as it is today, so her grandparents had to keep that information hidden and protected.

Today, Magicskin hides nothing. All her medicine is out in the open; her beads, her spruce roots, her leather. She attends ceremony regularly and planned her daughter Sharlee’s first sweat lodge ceremony when she was just four years old. Sharlee was surrounded by her parents, people she knew and trusted. It was a natural part of life, a rite of passage.

“I make sure our culture and spirituality is always there and always accessible, I’m role modeling it as a parent,” says Magicskin.

Magicskin remembers when she was a young child, along with all her cousins, the summer they helped their grandparents build a cabin. From hauling trees out of the bush to debarking them, and knowing that log cabin that still stands to this day, is one of Magicskin’s greatest memories of the time spent on the land with her grandparents. It survived and stands strong. Just like today’s youth being raised by strong Anishinaabe mothers.

“When I think about what’s important for my daughters to learn, it’s to go to the land, that we are connected to the land. So if you’re feeling sad, if you’re feeling lost, go to the land. It will make you feel better,” says Magicskin.

This Mother’s Day will mark the fifth anniversary of collecting garbage off Anemki Wajiw for Oliva Pelletier and her family. Her biggest hope is to see less garbage and to see more moms and families teaching their children the importance of taking care of Mother Earth as their own mother.