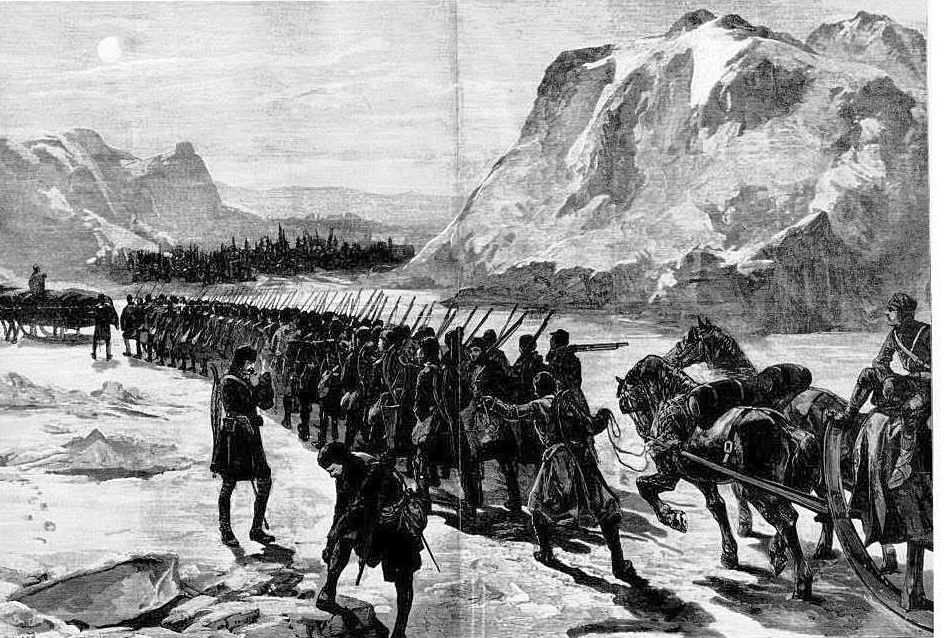

The Rebellion in the North-West Territory of Canada (Northwest Resistance of 1885): Colonial Troops marching over the ice of Nipigon Bay, Lake Superior, Ontario: 1885. | LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA

Nipigon—The extreme terrain along Lake Superior’s northern shore had a part to play in the first all-Canadian war. But what is not documented in the history books, is what was actually going on in Nipigon, when the 1885 Northwest Resistance unfolded.

It started when the newly formed Canadian government decided to expand westward. A plan that probably would have went a lot better than it did, if the officials had consulted with the Métis already living in the area. But seeing these people with mixed heritage more as squatters than rightful owners of the land that they had cultivated, the Minister of Public Works sent surveyors to the Red River Settlement in 1869.

Louis Riel was born in the Red River Settlement, located close to where Winnipeg is now situated. At the age of 14, he went to Quebec to become a priest. When his father died, Riel stopped his studies and worked as a law clerk to assist his family. He then moved to the U.S. and in 1868, he returned to the Red River Settlement. Understanding the underlying implications of the surveyors’ unannounced presence, the charismatic man warned the people. This led to the Métis National Committee forming a provisional government, choosing Riel as their president. A clash between the two governments quickly ensued, resulting in Thomas Scott being executed and Riel returning to the U.S.

This same struggle was going on for the Métis in Saskatchewan. They, too, were concerned about the government’s intentions, so they elected Gabriel Dumont to be the leader of the Saint-Laurent Council. Born in Saint-Boniface, Dumont spoke many languages and was a skilled hunter and military strategist. Like Riel, he had the trust and respect of his people. The newly formed North West Mounted Police (NWMP), later known as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, quickly disbanded the Saint-Laurent Council. Dumont and his fellow Métis continued to petition the Canadian government for assistance and assurance that their lands would be protected from new settlers. But just like the Métis in Manitoba, their concerns and rights were ignored.

Frustrated with the Canadian government’s lack of support, Dumont and a small group of people sought out Riel in the U.S. He agreed to join their cause and came to Batoche with them. The Métis set up a new provisional government. Riel was once again given the position of president and Dumont was the Adjutant-General. On March 26, 1885, Dumont and his troops defeated the NWMP at Duck Lake. On April 2, the son and supporters of Cree chief Big Bear, who were also upset with the Canadian government, killed nine settlers at Frog Lake.

The Canadians back east were horrified. Fearing more Aboriginals would unite and follow, the government decided to take action. And there was no shortage of men wanting to take up arms against the Aboriginal people. Only problem was that the Canadian Pacific Railway wasn’t finished and when the 10th Grenadiers arrived in Nipigon, they had to walk across the bay. It was evening and the pelting rain slowed them down as they trudged through the slushy snow. In Pierre Berton’s book, The Last Spike, it described the tremendous effort it took. “All attempts to preserve distance under such conditions had to be abandoned; the officers and men linked arms to prevent tumbling.” It took them six hours to get to Red Rock, where a passenger train was waiting for the soldiers.

Sir Frederick Dobson Middleton, Major-General was in charge of the Canadian troops that were sent to stop the 1885 North-West Resistance. A four-day battle took place in Batoche. On May 15, Riel surrendered. He was charged with high treason and hung. Dumont escaped to the U.S. Over the years, there has been a lot debate about the role Riel and Dumont played in Canada’s formation. Some people viewed them as traitors, but others saw their efforts to stand up for the Métis as nothing less than heroic.

There are people in the Nipigon area that claim when the Canadian soldiers were making their trek across Nipigon Bay, they were being observed by Riel and Dumont’s spies. There is no documentation to support this, but as pointed out by many historians, there hasn’t been any formal research into what the Métis and First Nations in other parts of Canada were doing during the Resistance. And with their history being primarily oral, it may never be known.