A Wild Workshop

When Charlotte Brontë wrote the preface to the 1850 edition of her sister Emily Brontë’s novel Wuthering Heights, she described how the novel was inextricably tied to the Yorkshire moors where the sisters lived. Wuthering Heights, Charlotte said, was “moorish, wild, and knotty as a root of heath,” and had Emily lived elsewhere, “her writings, if she had written at all, would have possessed another character.”

When we are taught about story structure as children, we are taught that the setting is where and when a story takes place. But far more than a mere backdrop, a deep sense of place can almost be as much of a character in a story as the people in it, and can be the reason that an author starts writing at all. Here in Northern Minnesota, the forests, lakes, and wilderness have been the source of inspiration for many authors who weave together place and story in their work.

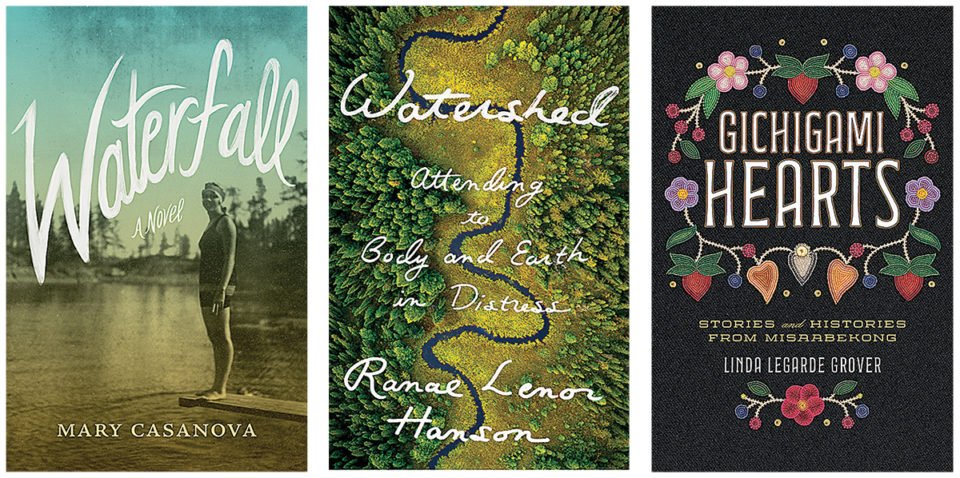

For Duluth author Linda LeGarde Grover, a sense of place is deeply connected to history, culture and family, as told in her book Gichigami Hearts: Stories and History from Misaabekong. Gichigami Hearts tells the story of The Great Migration of Anishinaabe/Ojibwe people from the Atlantic Coast to the Great Lakes. Underpinning all of the stories is Misaabekong, the geological formation also known as the Point of Rocks, which runs through Duluth.

“The sense of physicality in time and place is present in this book and inseparable from my own family’s history,” LeGarde Grover said. “That mass of gabbrous rock provides a foundation and solidity for life here in this region, lived against the backdrop of the natural and spiritual worlds.”

From the beginning of the book and the stories about the early arrival of the Anishinaabe to Lake Superior all the way to the end and the stories of her own family, LeGarde Grover’s stories all tie back to the Point of Rocks.

“The combinations of memoir and essay, fiction and nonfiction, prose and poetry in Gichigami Hearts is a presentation and format that is new to me while at the same time reflective of traditional Anishinaabe/Ojibwe recounting of history, cultural and spiritual beliefs, and endeavors along the road to Mino-Bimaadiziwin, the living of a good life,” she said.

Author Mary Casanova’s work is also rooted in her ties to Northern Minnesota. Nature, she said, finds its way into all of her writing. Casanova’s newest novel, Waterfall, follows the story of Trinity Baird, a young woman living on the Minnesota/Canadian border in the 1920s, and her struggles with mental health. Trinity Baird was inspired by the story of Virginia Roberts, the daughter of a wealthy family who spent the summers on Rainy Lake, and were friends with the environmentalist Ernest Oberholtzer. Casanova’s writing process involves blending together real-life inspiration and locations with new ideas.

“Along with Waterfall, my earlier novels, Frozen and Ice-Out, are also set in the early 1920s on the northern Minnesota border,” she said. “I feel I have been living in that era—a century ago—for some time now. During this long stretch of writing and research, I become a sponge, soaking up every aspect of history and culture I can uncover.”

Casanova said that her early writing process is often driven by a haunting idea or questions of injustice. In the case of Waterfall, it was learning that women could be committed to an asylum based on the word of family alone, with the diagnosis of “hysteria” used to cover a long list of behaviors that were considered unacceptable for women. Following research, Casanova begins by writing a few scenes, and continues to add detail and depth with each revision.

“It is through the writing that I figure out what I think; with each story I am ultimately trying to understand what it means to be human,” she said. “Waterfall is a story of hope and survival—that you can seemingly go over a waterfall—and yet somehow survive. It’s an empowering story of one young woman’s journey from utter brokenness to wholeness.”

Another Minnesota author who weaves together stories of challenge and hope is Ranae Lenor Hanson. Her book Watershed: Attending to the Body and Earth in Distress details her personal health journey after being diagnosed with a chronic illness, and juxtaposes this diagnosis with a look at the state of our ecosystems and the world’s climate.

“The book celebrates the watersheds of Minnesota, and particularly of the Northeastern part of the state, and honors the ethics of the Ojibwe and of respect for diverse and ongoing life,” Hanson said.

Four strands run through the book: the first is about Minnesota’s watersheds and Hanson’s childhood near the headwaters of the Kawishiwi River; the second about the climate crisis and stories of climate refugees; the third about Hanson’s diagnosis with Type 1 diabetes; and the fourth is on the ethical foundation for life, with opportunities for the reader to take action.

“The diabetes diagnosis and crisis surprised me by helping me with my despair over climate disruption,” Hanson said. “Once I had a body that depends on 24/7 intervention, I became more comfortable about a world that will need 24/7 intervention because its natural systems, like my body’s, have broken. Then, too, the attentions that I have to pay in order to stay alive now parallel the attentions that all people need to make to keep the earth’s life support systems going.”

While each author arrives at the blank page for different reasons, and with different stories to tell, a shared love of this special region—including its rich history and sometimes uncertain future—unites all of the books that were hewn in this wild workshop.