The kayak bobbed gently in the negligible swell as the bow probed the sea cave-like cavity at the base of a rocky wall. More caves and even a few arches farther up the shoreline awaited the kayakers, along with towering palisades hundreds of feet high looming out of the clear blue-green waters.

Back out on open water, overhead, headlands rose up beyond the shoreline, sometimes abruptly plummeting to the waters far below. A thick, dark green pile, the northern boreal forest, carpeted the mountain-like summits and ridges. On the other side, a vast body of water disappeared beyond the slightly curved horizon. The scene would maintain its alluring grandeur along most of the 170 miles of shoreline encompassing the Lake Superior State Water Trail.

It’s the greatest of the Great Lakes, “Gitchi Gummi” to the Indigenous tribes along her shore. At 32,000 square miles, it’s the largest lake, by surface area, in the world, holding 10 percent of the Earth’s fresh water. Some kayakers call it the Inland Sea. By disposition, it’s basically an intra-continental ocean. Its tides are barely discernible. Rather its waters move within a big geological basin, sloshing around like in a huge bath tub.

Extended kayak touring along this shoreline is not for the faint of heart—nor faint of skills and equipment. Small, recreational kayaks are best suited to paddle near public beaches or within protected bays. Specifically designed for big water touring, sea kayaks with water-tight bulkheads, additional flotation gear bags and a rudder/skeg are best suited for these Dr. Jekell and Mr. Hyde waters.

“Water and wind can change in a matter of minutes,” warns Travis Novitsky, park manager at Grand Portage State Park. “It can go from calm to 6-foot seas, waves from three different directions—sloppy, messy seas,” he adds.

The water trail traces the shoreline along its entire route that begins near the High Bridge in Duluth Harbor, northeast to the tip of Pigeon Point at Grand Portage. Five state park boundaries define some of that shoreline that is also speckled with numerous boat access points, take-out rest areas and a few Water Access Campsites.

Beginning at Gooseberry Falls State Park (Mile 51) cliffs and beaches dot the shore along past Split Rock Lighthouse State Park and past a shallow-water shipwreck at Gold Rock Point (Mile 59). Ten miles farther at Tettegouche State Park, sea cliffs and caves lure paddlers to approach.

Superior’s waves are steeper, with shorter wave lengths than in the ocean. Wind generated waves smashing into vertical rock walls create a menacing standing wave action, called clipotis, that forms when rebounding waves slam into in-bound waves, creating an often explosive, stationery “high five” standing wave just out from the wall of rock—a menace to paddlers.

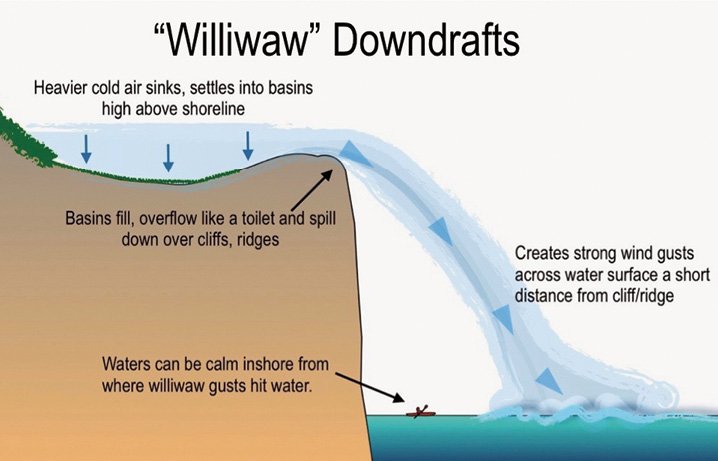

The coastal landscape along the trail couples geological beauty with tempestuous wind/wave action. Inherent dangers include williwaw winds (cold air flowing down from the highlands, gusting out across the water), and steep, cobbled beaches with dumping surf that can hammer a kayak—and paddler—against a rocky landing site.

The average kayak touring speed is 2-3 mph. There are a few stretches (before Two Harbors, from Tettegouche to Temperance River State Park and the Grand Portage Indian Reservation) where there are no public access landing sites for 6-10 miles. Kayakers need to carefully time their point-to-point or out-and-back touring to be able to reach a safe haven, should paddling conditions begin to deteriorate.

Kayakers should have at least intermediate level skills and dress properly to protect against possible immersion in waters that rarely reach beyond 50 degrees F in summer (3mm neoprene bibs or dry suit; firm-soled paddling shoes/booties; and a proper-fitting PFD/Life Jacket). Good exit/self-rescue or assisted rescue skills are vital. Less experienced paddlers and enthusiasts should consider a kayak touring operation as their first introduction to these waters.

The Minnesota DNR has four-set Lake Superior Water Trail maps depicting shoreline attractions/amenities. NOAA also has sectional Navigational Chart Maps. Old fashioned compass skills are also helpful during bay crossings in fog. Highway noise and the unchanging NE shoreline on northern-bound paddlers offers reliable orientation, too.

KIG64 marine forecasts and VHF weather-band channels provide weather information (and VHF for emergency hailing). And, no, cell phones are not reliable.

To best enjoy these waters, make sure your kayaking skills are solid and know your limitations. An enjoyable introduction to this incredible inland sea shoreline is through a day-tour kayaking operation where all your gear and professional instruction is provided.

Paddling the North Shore is a double-edged sword: keen, gleaming big water vistas, towering, sculpted cliffs and scenic bays to enjoy and admire—but coupled with sometimes quick-to-anger seas that need to be heeded and respected.