The Canada lynx is one of the least-seen large animals in the boreal forest, a reclusive predator that spends most of its time in places where people don’t go. During the 1990s, some wildlife experts postulated resident lynx were largely extirpated from northern Minnesota, aside from individual cats roving from Ontario. It was a theory that held sway until more folks began reporting their lynx sightings, including photos of kittens taken by a logger in Isabella.

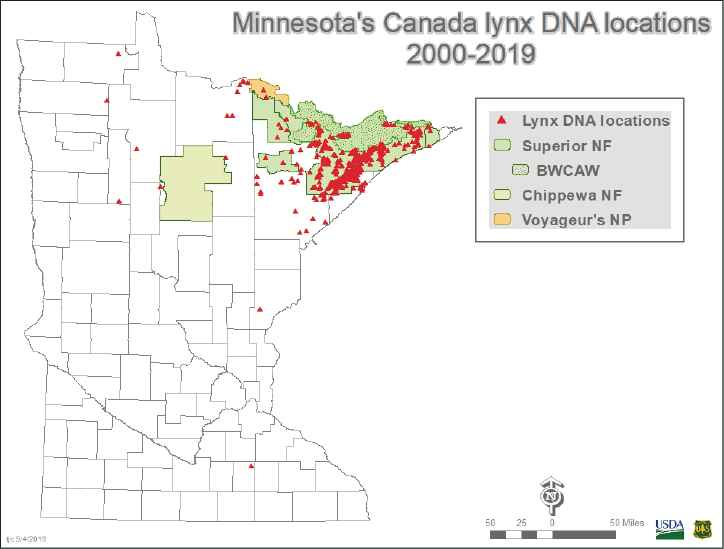

Beginning in 2000, wildlife researchers set about learning more about Minnesota’s elusive wild feline, painstakingly following lynx tracks in the snow to find scat or hairs that were used to collect DNA samples and begin building a database. A radio telemetry study begun in 2003 allowed biologists to monitor collared lynx and learn about their range and movements. While the radio-telemetry study ended about 10 years ago, snow-tracking occurs every winter. Over time, a clearer picture of Minnesota’s lynx has emerged.

Superior National Forest wildlife biologist Dan Ryan coordinates lynx tracking efforts and helps maintain the existing database and recently released a summary of 2019 DNA database and population monitoring. The report’s summary describes the impressive amount of information that has been collected over two decades:

“The current database contains 1,992 samples that have been submitted for DNA testing. Mitochondrial DNA analysis has identified 1,666 of them (83.6%) as lynx. Nuclear DNA analysis has determined 413 unique lynx genotypes, 199 female (48.2%), 212 male (51.3%) and 2 of indeterminable sex (0.2%).

“Since 2010, 44 family groups have been identified producing 92 kittens that survived to the winter following their birth, 51 female (55.4%) and 41 male (44.6%). Reproduction has been documented on the Superior NF every year since 2001. Of the 355 individuals that were identified prior to this survey season and were not originally detected as a result of a mortality, 88 (24.8%) are known to have persisted into a second year. Eight individuals have persisted for over 6 years.

“During the 2018-2019 survey season 157 samples were collected and submitted for testing. One-hundred fifty-three (97.5%) were identified as lynx, 142 of those (90.4%) were able to be genotyped identifying 59 individuals; 32 female and 27 male. Twenty-six individuals (47.5%: 12 female and 14 male) were previously recorded in this database (recaptures), and 33 individuals (52.5%: 20 female, 12 male) are new to the database this year. Field observations suggest that there were at least 12 family groups with as many as 30 kittens found in the survey area. DNA analysis confirm 7 family groups with 10 individuals (7 female, 3 male) genetically consistent with being offspring. Of the 24 individuals identified this survey season whose age is known that were not kittens, 14 (56.0%: 9 female and 5 male) have persisted for at least 2 years. Twelve (52.2%) have been detected into their third year or more indicating persistence in the population. Three individuals (13.0%) detected this season have persisted on the Forest for over 6 years. There are 25 individuals new to the database this year whose age could not be determined.”

Remarkably, the DNA database not only allows researchers to track individual lynx from year to year, but also to identify multiple generations of lynx family groups.

“A lot of the breeding females are Minnesota-born lynx,” Ryan said. “We can track some animals back four generations. You kinda get to know them.”

Lynx are closely associated with their primary prey: snowshoe hares. Ryan said Minnesota lynx feed almost exclusively on hares. In locales with adequate densities of hares, lynx hang around. If hares are few, the cats move around more. Occasionally, Ryan has found areas with plenty of hares, but no lynx. Often, roving lynx eventually discover the untapped food source.

Bobcats are common across most of Minnesota and sometimes mate with lynx, creating a sterile hybrid. Ryan said DNA testing has turned up one or two hybrids per year. He thinks hybrids are more aggressive than lynx and that hybrid males may keep lynx away from their territory. Fortunately, bobcats cannot compete with lynx during snowy winters. Lynx have big, furry paws that allow them to stay atop the snow. Bobcats do not and typically disappear from the lynx range during deep snow years. The snowiest portions of northeastern Minnesota—inland from Lake Superior in Lake and Cook counties—are a stronghold for lynx, supporting the highest numbers of the cats.

The tracking survey is limited by available staff time and, to a certain extent, receiving timely reports of lynx tracks and sightings. Remote places such as the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness are not surveyed. This coming winter, Ryan will have a few extra boots on the ground. The Forest Service is hiring seasonal workers to snow-track lynx and gather more DNA samples. The funding is available via the Polymet mining project, because the company is committed to providing money for lynx monitoring over 10 years. The data will also be used to inform a coming U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposal to delist lynx from their current Threatened status under the Endangered Species Act.

Ryan said the public can report lynx sightings to him by emailing danial.ryan@usda.gov.