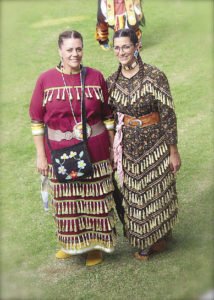

This year, Brandy Morris will dance at the Fort William First Nation Traditional Pow-Wow.

“When I’m dancing I feel like the true me and proud of where I come from. I’m a humble person and I don’t always take compliments so well, but when I dance, I feel proud and I want to show it. Your heart swells with pride, and you get teary, but you are so happy at the same time,” Morris said, explaining how it feels to enter the powwow and dance. “Your mind is clear. You lay your tobacco. You pray.”

Morris, now in her early 40s, started a life-changing transformation two years ago. It began with a sewing machine, ribbon, bias tape and 300 jingles. She is the healthiest of body, mind, and spirit than she has ever been. It all started from the simple act of reconnecting to her culture. She now gets a lot of compliments on her dancing, beading, and for sharing her cultural knowledge. Morris has been told she looks like she has been dancing for years, “a real natural.” While dressed in her regalia, dancing, she feels like royalty on this land.

She is looking forward to traveling the powwow trail this year, reconnecting with the “powwow family” she has made during her regalia making process. The jingle dress and dance is well-known to the Anishinaabeg and other Indigenous peoples across North America. It is known as the healing dance. The birthplace of the dress is Naotkamegwanning First Nation in the early 1900s. According to stories passed down from spiritual advisors at the powwow, the granddaughter of a medicine man was ill, so her grandfather prayed and asked for help. He was gifted the vision of the jingle dress and dance. Four women made their jingle dresses and danced for the ill child. By the fourth round of drums, singing and prayer, the ill child was up, following the dancers, dancing, healing. The jingle dress is a gift.

Morris was born and raised on the territory of Anemki Wajiw, which translates to Thunder Mountain, also referred to as Mount McKay, on Fort William First Nation near the city of Thunder Bay. She has been attending her traditional powwow nearly all her life, but only as a spectator. This year will be her first time dancing there. Morris dreamed of being a jingle dress dancer as soon as she saw one at her first powwow in the 70s. As a young girl, she can remember watching the dancers go by, being mesmerized by the sound of the jingles. There was an overwhelming feeling of love for the jingles that she has held onto all this time.

As Morris was making her regalia, she was also practicing her dance steps for Grand Entry, the moment everyone is asked to enter the powwow. She would practice at home and every free minute. She downloaded powwow music onto her phone, watched a YouTube tutorial video, and danced. Morris shares with family and friends how the dress makes her feel pride, connection and healing. It’s also brought her back to beading and being on the land.

Her jingle dress colours are green, purple and white. Her handmade leg-wrap moccasins are white leather. Her regalia didn’t come overnight. It was two years in the making; each jingle was secured onto the bias tape, ribbon was sewn onto the dress material, and the biais tape was sewn onto the ribbon.

Morris was gifted hand-beaded earrings, a headpiece, and choker from her friend Stephanie MacLaurin, who is no longer dancing. The beadwork was originally gifted to MacLaurin when she first began dancing. MacLaurin told Morris the beads should be dancing, not sitting on her dresser jewelry stand.

Elysia Petrone, also of Fort William First Nation, has a somewhat different story.

“As a child, I felt ashamed of being an Indigenous person. Kids would tease me, call me wagon burner and all sorts of names. So I would lie and only focus on my father’s Italian heritage, and for the most part, it worked. I passed as Italian and my last name is Petrone,” she said.

Her maternal grandmother hid the fact that she was an Anishinaabe’kwe (an Anishinaabe woman). Petrone understands why her grandmother tried to shield her family from colonialism and the violence that it brought. Colonialism aimed to destroy the Anishinaabeg way of life.

However, Petrone is set to change that. Her friend Aandeg Skelly, who is a local historian, dug up news articles and census reports on her family. The Anishinaabe side of her family lineage could be traced back many generations. This created a shift in Petrone’s feelings about herself and her culture.

“I know my grandparents were praying for me. I went from being embarrassed for who I was to pride,” she said.

Petrone has since enrolled in Anishinaabemowin (Anishinaabe language) classes and is always up for land-based learning. Together with a group of friends, she, like Morris, has made her first regalia. Everyone played a part. Petrone bought some of the supplies and was gifted the rest. She attached each jingle, all 300, to the bias tape. One friend took the lead and sewed up the dress. Another friend made her moccasins, while another still made her belt. Lastly, they brought her and the dress into ceremony. It was there that Petrone learned the full history of the dress and the intent behind the dance. The jingle dress is a healing dress and it was exactly what she needed.

From the beginning of European contact, the Anishinaabeg have experienced colonial violence. Their lands were taken away. Children were taken from their homes and parents, most often sent far away to residential schools where they faced their own horrors. Ceremony and spiritual practices were outlawed. The Anishinaabeg continue to face colonial violence today—but more and more Indigenous people are remembering where they come from and reconnecting to the land. Through this process, they are healing themselves. They continue to show resilience, strength and pride.

“The powwow brings people together. It brings me joy when we gather, share food, spend time together and bond. It’s a safe space for us to do that, a space for spirituality because you pray as you dance,” says Petrone.

All are welcome in the powwow circle and you are never too old to begin. Fort William First Nation’s Myria Esquega proves that. Esquega has been around powwows her entire life. She also drums and sings, and volunteers her time to helping others. Esquega was just 12 years old when she danced for the first time, but she was very shy and would not dance again until her sixties.

“I always knew what the jingle dress did for our people; I heard stories long ago that it’s a healing dance and I believe in the healing the dance brings,” says Esquega. “It’s an honour for me to wear my regalia.”

Regalia that she made herself after being given her colours in ceremony. She is returning to her roots for healing and it all started with an offering of tobacco.