No names. This story isn’t about the people. It’s about the history and connection that modern man has with ice. It’s about the science and technology used to harvest the ice, and it’s about the purpose for pulling the ice.

A retired mechanical engineer joined an ice cutting crew about 10 years ago, and he describes his experiences as an ice-maker. All the ice-makers have a job on the frozen lake and one of his roles, he says, is to remember the lore and to honour the spirit of the ice with an opening prayer at the ice hole.

“When you’re on the ice, you think differently,” he said. “We are blessed in northwestern Ontario. People think it (the cold) is a curse, it’s a blessing.”

Before chemicals transformed refrigeration technology, ice was a very important part of everyday life. The settlers cut ice from lakes and filled ice houses to keep milk and cream cold. Ice was used in the passenger cars of trains to keep the travelers comfortable. Even buildings were cooled by using ice. In the 1880s, Chicago saw a surge in high rise buildings which needed air conditioning. As a coolant, ice was harvested from Lake Michigan, but even more ice was needed than could be supplied locally. As a result, highly valued ice was transported from Lake Superior to meet the demands. Even into the 1950s, the ice delivery man brought ice to homes and businesses. For a cool treat, he would toss ice chips to the kids following his ice truck on hot summer days. Moreover, industry relied on ice. For instance, fishing communities along the shores of Lake Superior, such as Rossport, Jackfish, and Port Coldwell, needed ice to transport their fish on the Canadian Pacific Railway.

The ice-maker first experienced ice harvesting in 1973 when an elderly couple, and proprietors of a fishing business at Silver Islet on Lake Superior, were in need of help. At 72 years of age, the wife would cut the ice from the lake with a chainsaw and the husband pulled the blocks from the water. However, extra hands were needed to load the ice onto a skid that would then transport the ice to the ice house.

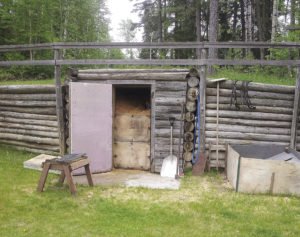

The process of collecting and storing the ice is not as simple as one might think. It involves science, ingenuity and cooperation. But before the ice-makers can take on the ice, the ice house must be prepared. One such ice house is cut into a hillside and its features include Styrofoam insulation, a concrete floor, and a façade made of logs. The ice house was built by a retired steam and recovery superintendent, who is held in high regard for his experience and knowledge and is referred to as the ‘Ice Master’ or ‘Ice Meister.’ To ready the house, it will first be surcharged with cold by keeping the doors open for weeks. Just as a thermos is surcharged with hot water before filling with hot coffee, conversely, the frigid nights will chill the interior of the ice house.

Likewise, the lake site must be prepared. Snow will be removed from the surface of the ice. Snow acts as an insulator, so by removing the snow, the water below can freeze more quickly to the desired thickness of about two feet. Next, the ice is scored at a width of 14 inches with a chainsaw. The ice is cut deeply but not deep enough to cut through to the water. The chainsaw is attached (blade down) to a skid that resembles a short kick sleigh, and the saw can be adjusted for the variation of thickness in the ice. After all of the blocks are scored in both directions to make a checkerboard pattern, the first cut is made through to the water, which is called the plunge cut. Once the first cut makes it through the ice, water gushes up and fills the score lines, so the crew must work quickly on the slippery surface. The lines must be kept visible and slush must be cleaned off. After the first 14 by 14-inch square is cut on all sides and the block of ice is free, it is pushed down into the water. The block then pops back up like a cork. When the block bobs up, it is grabbed by ice tongs and pulled from the water. Cheers erupt from the crew as the first two-foot-long block is birthed from the water. The foggy, opaque top layer, called creamy ice, transitions to a crystal clear glass cube. The men and women on the crew continue to free blocks of ice, cutting, pushing the blocks towards the edge with a picaroon, and pulling the blocks to the surface. It takes a full day to harvest the 70 blocks (about five tons) of ice for each of the three ice houses. Before leaving the lake, though, one last important task is required: to guard the hole. Trees are put up around the edge of the site to warn others of the open water.

Before the blocks are brought to the ice house, the creamy ice, the top layer that is foggy and opaque, will be cut and separated from the clear ice. Creamy ice has more air in it and will melt faster, so it is ideal for cooler ice whereas the clear ice has less air and will melt slower. Therefore, the clear ice is the more valued ice.

At the ice house, Ice Meister organizes the blocks. The creamy and clear ice blocks will be organized and stored separately. Snow is then packed between the blocks. The whole lode is then covered with wood shavings and sealed in the insulated house.

When the work is all done, the crew celebrates by sampling the ice crop, dining well, and having a sauna. All the while, they talk about the day and problems solved. Each year, techniques and tools are improved based on traditional knowledge and experiences. Many of the tools the crew uses have been tweaked or designed by the Ice Meister to be more efficient.

“It goes deep in your psyche,” said the ice-maker.

Finally, in the heat of a summer day, the ice house is opened. A block of clear ice is placed on a grate suspended on work horses. A gravity-fed water source supplies water to rinse the shavings from the block. The creamy ice is packed in a cooler, and at last, the clear ice fulfills its noble end, said the ice-maker. When he looks at the ice slowly morphing and melting in his drink, he feels the cold on his face from the January breeze. He sees his fellow crew people working in unison on the ice. He remembers the old woman in the ‘70s who was so happy to be cutting the ice, and he looks forward to the next harvest.

“It’s the value that you receive when you’re looking at the ice in your rum. By the last drop of the bottle, your mind expands and allows you to reflect and regale these thoughts and the more guys you have involved, the richer the picture.”