In the summer of 2020, a beautiful public art installation appeared on some of the most commonplace of items in the city of Grand Marais: the city’s trash barrels had been transformed from ordinary-looking bins to being adorned with bright colors and paintings of fish. These paintings, with names in both English and Ojibwe, were the work of Ojibwe artist Sam Zimmerman. With descendants from Grand Portage, Zimmerman is a painter and school administrator based in Duluth. While his life has taken him in many different directions, two years ago he felt a longing for home and a desire to return to painting that led him to where he is today: living, painting and storytelling on the shores of Lake Superior.

Zimmerman’s journey to becoming a full-time artist began when he was attending school on the East Coast as a pre-law student. By the end of his sophomore year he had completed a handful of paintings and knew that pursuing law was not what he wanted to do. And so, he approached the chair of the art department with his paintings and said that he was interested in becoming an art major. The department chair saw his work and said he wanted Sam in the studio the next week.

“My father always told me to follow my spirit,” he said. “There’s a fear in doing that, and you wonder if it’s the right decision or if it will pay the bills. But it’s something we all need to be reminded of, that you need to follow your spirit.”

Zimmerman finished his undergraduate degree in painting and anthropology and moved to New York City to pursue his art career. While there he worked at a summer camp for children with disabilities, an experience that instilled in him a love for working with children. He quickly went from being a working artist to being a middle school art teacher for children with disabilities. For 20 years he worked in education, eventually becoming a school superintendent.

However, living on the East Coast meant being far from family, and he began to feel the pull to follow his roots back toward his home of northern Minnesota. Around the same time, he took a trip to Alaska, where he was immersed in the beautiful Indigenous art from the area. He realized that not only did he miss painting, but that he had never painted the stories from his heritage. In the summer of 2018, he picked up a paintbrush for the first time, and in July of 2019 made the move from the East Coast to Duluth.

Zimmerman describes the time from beginning to paint again to the present as somewhat of a whirlwind: he went from a hiatus as a working artist to completing 120 paintings in two years and having his art featured in multiple gallery exhibitions since then. But through all the rapid changes, capturing stories continually lies at the heart of what he does.

“In general, painting is about capturing an emotion and expression, but for me, painting is about telling a story,” he said. “So much of Indigenous wisdom is passed on in story, and so much of our culture revolves around an elder telling you the story. Yet you won’t ever find a book with all of them, because they have to be lived in real time. When the Elders are gone, the stories are gone, and that’s one of the reasons that I’m being so prolific in my painting now.”

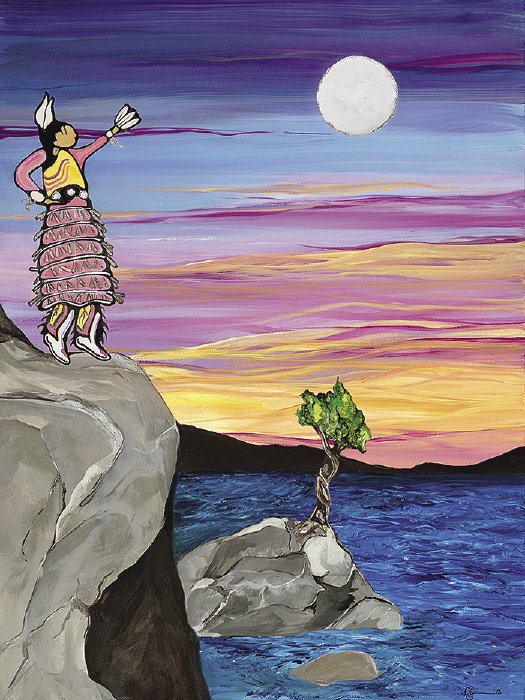

Zimmerman’s style borrows from the Woodlands style of art pioneered by Norval Morrisseau, but also uniquely incorporates his own personal background and training in realism. Each piece captures a particular story from his heritage, and is laced with rich symbolism and hidden detail. For instance, one of his paintings honors the sturgeon and has seven trees for the Seven Grandfather Teachings, as well as 153 dots on the sturgeon to represent the age of the oldest known Lake Superior sturgeon; another painting honors the pike as a predator, and has agate-like swirls on the fins. Some of the symbolism is more personal; one painting has the number of stars that correspond with how old he was when he completed the painting, and another has a tree for each of his siblings.

When asked how long it takes to complete a painting, Zimmerman said it varies from a few days to a month; he often has a few paintings going on at a time, and will work on each in turn depending on where his inspiration takes him.

“I can feel it in my hands when I’m on the right track, and there’s a certain energy around a piece when it’s going well,” he said.

Since he began, the response to his work has been strong. As mentioned earlier, Zimmerman has had three gallery shows since moving back to Minnesota, and became the first Native artist in Duluth to have a solo show at a traditionally white-owned gallery. He has also connected with people who have reached out to him to have their own stories told through art, often finding special and even serendipitous connections.

“I’ve had multiple people who have come up to me since I started painting who have said that there’s a reason that you’re doing what you are, when you are,” he said.

In addition to his paintings, many will also recognize Zimmerman’s work from the public art project that he did painting trash barrels for the city of Grand Marais. His idea was to have barrels that are both visually striking—so people would be encouraged to use them—and to also educate people about the Ojibwe community and culture. He chose to paint fish since the responsible handling of trash is a way to care for the waters; he painted six, well-known fish species, including two that are threatened, each with the English and Ojibwe names. Now there are six more painted barrels being added, with three animals and three birds: a fitting reminder to how our actions affect the wildlife on land, sea and air.

Beginning this month, Zimmerman will be writing a column, titled “Following the Ancestors’ Steps,” for Northern Wilds. Each month he will share a different painting as well as the story behind that painting. Readers will get to see his art and learn about the stories, traditions and hidden gems behind each piece.

In addition to his art, Zimmerman is a special education director in Duluth. His plan is to keep using his gifts in art and in education to inspire and to teach.

“I love my culture and my heritage. In the world that we’re living in right now, I want to be someone who can be a catalyst for beauty and joy as much as I possibly can.”

Sam Zimmerman’s work can be found online on Instagram and Facebook under the name Crane Superior.