My First Opener

By Christopher Pascone

My identity as a non-native Minnesotan “looking in” is strongly defined by what happens on fishing opener. I get one day a year to prove to myself, and everyone else, that I belong here. Probably nobody else cares how “Minnesotan” I am, but that doesn’t diminish the significance of the day for me. I take it seriously.

I know that fishing opener traditions are what make Minnesota the place it is. That’s why creating my own opener tradition was one of my main aims when I moved my family to Duluth from St. Petersburg, Russia in 2014. Even if I wasn’t “one of us,” I had to get some skin in the game. I was desperate for a proud experience to relate to my new Minnesota friends.

On the big first opener, my friend David Leason and I headed to Boulder Lake, a reservoir a half hour north of Duluth. May I add that it was cold, windy and raw. Of course, snow had to fall as well. Boulder is a big, open body of water, and we would be paddling those waves from a College of St. Scholastica rental canoe. A day for dreams to be made. A day to “earn it.”

We got our sea legs under us as we paddled into the north wind, the chop occasionally sending spray over the gunwales. We were clueless where to go on the windswept lake, but observed a couple of old timers fishing very successfully from shore, so we pulled into the sandy beach to greet them and plead our ignorance. Turns out they were routinely catching walleyes by waiting patiently with minnow rigs off bottom. We, of course, hadn’t caught a thing. We got renewed energy and inspiration from the friendly fishermen and their awesome catch. It was a beautiful interaction: we didn’t have to beg for information, but rather were treated to the kind of support and advice that experienced fishermen have shared with beginners for millennia. We thanked them profusely, and since we had a canoe, were able to get off shore a ways to show them a respectful distance.

Using the local tip, we anchored, and—braving the surf—spent the next hour jigging up three beautiful walleyes and two jumbo perch. The largest walleye—a 24-incher—was my personal best (to this day!). Needless to say, we were hooting and hollering into the wind each time we netted another one. It was the ultimate feeling of achievement and belonging.

As one of my Minnesota fishing mentors commented to me later that day: “Wear your honorary lefse bib and lutefisk badge of courage with pride and honor.” How little he knew how important that was to me.

A Professional Catch (No Release)

By Casey Fitchett

Technically, I used to fish professionally. But before you start jumping to conclusions, let’s dissect this a bit.

The definition of professional is “engaged in a specified activity as one’s main paid occupation rather than as a pastime.” Just because you get paid to do something doesn’t mean that you deserve to be getting paid. Self-deprecation has a place here, I promise!

I moved to the North Shore when I was 22 years old. Fresh out of college, I hopped in a car and committed to living in a place called Lutsen for the next few months of my life. Having never been to Minnesota, much less the northern part of this already northern state, it was easy to use the word “flabbergasted” to describe my reaction as I melted into the otherworldly blue of Lake Superior the first time I drove up Highway 61.

Walking into my stunning, unique, architecturally-significant resort of employment for the first time garnered a similar reaction. I was reporting for duty as a member of the Activities Staff: an elite group tasked with the daunting responsibility of taking resort guests out kayaking, hiking and fly-fishing during their respective stays. Our job was to help others have fun and I took that expectation seriously.

I had been kayaking throughout my life, and slowly but surely I learned enough area information to be able to entertain the tourists on hikes. Whenever there was a fly-fishing lesson scheduled during my shift, however, I cringed internally. This was, without a doubt, basically the antithesis of my skill set. Would they be able to see through my simple regurgitation of fishing facts or would I be able to feign enough confidence to convince the travelers that I could be trusted to give them the trout truths and Chinook certainties they deserved?

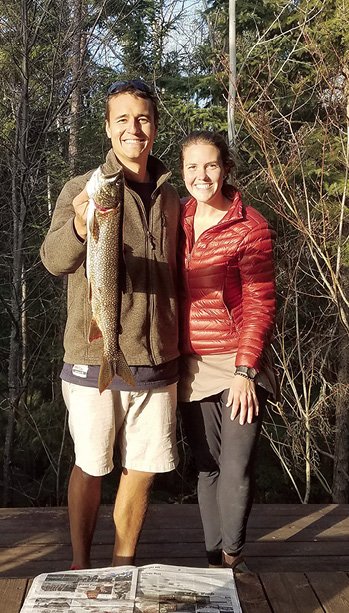

You would have to ask my participants for an honest review of the clinics, but I can tell you that I certainly gave it a good just-post-college try. My story really comes full circle over five years later: February 16, 2018. That was the day that I began dating a true fisherman. A man who did research ahead of time about the types of fish that a particular body of water held and committed that information to memory. He knew about types of underwater formations and the depths you should fish at different times of year. While this may seem basic to many fishing fanatics, I can tell you this is not the type of information that typically gets a spot in my brain vault. As our relationship progressed and we moved in together, I realized the true extent of the mild obsession as I stared at the mound of fishing gear that was now a part of my life as well.

Over the course of our three years together, I have fished more than I ever thought I would in my life. We’ve casted in perhaps the fly-fishing capital of the world in Patagonia, frozen lakes in the middle of the wilderness, and nationally-recognized streams and rivers in Montana. After learning what the phrase meant, I can confirm I’ve “horsed” it on more than one occasion, and I still haven’t quite gotten to the level where I want to learn how to clean the fish we catch (but I’m getting there). Always willing to share his knowledge patiently and clearly, he’s much more deserving of the professional title than I am.

I’ve landed myself a good one.

Living Life Against the Wind

By Joe Shead

The stresses of a busy summer had taken their toll. I needed to get away. Spur of the moment, I drove to one of my favorite lakes.

The lake was placid when I arrived. The still water was just what I needed to calm my frayed nerves. But soon after launching, the wind picked up. Within an hour, it was howling. I can fish in rain or snow, but when it gets windy, I stress out. It’s hard to control the boat, tie knots, heck, just function. I was trying to escape stress; not add more to my life! Soon, I was drifting at trolling speed, which I could almost feel delighted the wind in a sick, twisted way.

Well, maybe I could harness the wind to my advantage. I could sure cover water in a hurry, but I was moving too fast to fish effectively. I tried to take shelter on a leeward shore to fish a weedbed, but no luck. Now I motored far down the lake to try another spot. If that didn’t produce, I’d try all the way across the lake. I finally plucked one perch out of the weeds, but that was it. I fired up the motor to try another spot, but the prop wouldn’t spin. Neither forward or reverse worked.

I dropped the electric trolling motor in the drink, but even on high speed I could barely make headway against the unrelenting waves. I anchored to think things through before I lost ground. I could drift with the wind to the far shore. After all, there was a boat landing there. But the boat would be pounded at the dock and perhaps even swamped. Plus, I’d have to walk or hitchhike several miles to reach my truck on the leeward shoreline.

As I contemplated my next move, an approaching pontoon boat made it for me. I flagged down the operator and he drew up alongside. The wind was so fierce we could barely hear each other, but he agreed to tow me to the boat landing where he was heading. Imagine my good fortune! That was the first boat I’d seen on that secluded end of the lake.

Hooking up was a tricky proposition. I remained at anchor and he would swing near, but the furious wind swung him away or maniacal waves pushed him out of reach of the rope I threw. After a few attempts, he finally grasped the rope.

He had to get on the throttle right away or risk getting swept downwind and backing into me or over the rope. I scrambled to pull up the anchor and attach the towrope to my boat before it tightened and cut into my hands. All of this was complicated further by the waves, which made maneuvering in my boat akin to trying to stand in a child’s bouncy castle occupied by several exuberant children.

Somehow, I got the anchor rope pulled up and the towrope attached. And then, for the first time in hours, I just sat. There was no boat to steer. No trying to keep my fishing line out of the prop. No concentrating just to stand without being knocked overboard. The tow ride was the most relaxing thing I did all day.

It was slow going against the waves. The pontoon driver towed me at 3 mph. At times my boat swung back and forth. During gusts, I feared the rope would snap, but everything held tight.

For 45 minutes, I just relaxed and watched the waves go by.

Back at the landing I thanked my rescuer and tried to slip him some cash for gas and a nice dinner. He wouldn’t take it. I told him I could make the half-mile back to the resort on my trolling motor, now that I was on the lee side of the lake. Of course, I had to stop a few times and cast and managed to pick up enough perch for supper. All in all, not a bad day.

A Sucker for the Sucker

By Eric Chandler

I’m a terrible fisherman. But, so help me, I did my best to catch a steelhead for a decade. My buddies tried to teach me how to land one of these rainbow trout in the spring. They took me to the Arrowhead Brule, the Knife, the Lester, and the Baptism. I just never got the feel for how to bounce my egg pattern down the river so one of those steelhead would hit.

Then, finally, on the Sucker River the line screamed out of my reel as I hooked a steelhead. I tried to horse it in like a rookie and lost it. But, the tug is the drug, as they say. I went back to the Sucker over and over trying to replicate that moment. I stalked the riverbank like a penitent for years, thinking that the river would reward me for studying it so closely.

Early on, I turned to fishing the Sucker in the fall as a substitute. The water was lower and clearer. I saw king salmon make their fall run. They were so big they looked like dolphins. For two years, I caught a king salmon in the fall and simulated the feeling of a steelhead. After those first few years, I never saw a king again. Then, the smaller pink salmon were the only show in town on the Sucker in the fall. Fourteen years ago, my daughter helped me scout the river down to the shore. Eight years ago, I helped my daughter land a pink.

A while back, years of people littering and abusing the land along the lower Sucker finally came to a head. The private landowners on both sides of the river don’t allow access below Scenic Highway 61 anymore. Sad, but justified. From now on, I’ll only have the fond memory of walking out of the tunnel under Highway 61, through the trees, past the wide lagoon where the sky opens up, the water flows into Lake Superior, and smelling the fresh breeze. I’m a sucker for the Sucker. Maybe more so now that the opportunity to walk to the mouth is lost.

Six years ago, I finally caught a wild steelhead after a decade of trying. I knew every little bend and rock in the Sucker, but that’s not where I caught it. In a fit of desperation, on the way back to Duluth from getting skunked on the Baptism River, I pulled over at Silver Creek. The one and only time I fished there, I caught and released my first steelhead. I almost wept.

All this makes me think I should try to catch my second steelhead. One per decade is my limit, I guess.

Learning to Fly-fish in Labrador

By Elle Andra-Warner

Over the years I’ve fished in Lake Superior, inland lakes and rivers around Thunder Bay and even cod-jigged in the ocean waters off Newfoundland, but fly-fishing was something I had never tried. So, when an invite came to learn fly-fishing on the Eagle River in Labrador—one of North America’s world-class fly-fishing areas for wild Atlantic salmon—I gladly accepted.

A Twin Otter bush plane flew us the 150 km (90 miles) from Happy Valley-Goose Bay to our river base, the remote Rifflin’ Hitch Lodge located about 37 km (23 miles) from the mouth of the Eagle River. What was really cool about this lodge was it was designed by a woman Gudrig “Gudie” Hastings. She and her construction crew had lived in tents while clearing over 3.5 acres of land along the Eagle River, then choppered in native spruce, pine and juniper and built a 7,000-square-foot luxury wilderness lodge.

I was the fly-fishing novice among the other three guests, all Americans. The lodge provided us with the fishing gear plus a fishing guide for every two people. My fishing partner for the five days was an award-winning photographer from Idaho on a magazine assignment; as a bonus, he provided photography tips including how to take the ‘perfect’ fishing picture (good credentials—his ‘laughing horse’ image had earned him already more than $1 million in royalties).

And how did my fly-fishing go? Pretty well, thanks to our boat’s guide Andy. I learned to fly-cast (it’s all about the technique, not power), read the slick water (a whole new angler lingo) and do the easy method of dead float fly-fishing (cast and just let the fly float with the current but keep the line off the water). The lodge’s catch-and-release policy included letting us keep one salmon for the culinary staff to prepare for dinner and yes, the last afternoon I did finally land an Atlantic salmon to contribute to the evening meal.