Northern Wilds Magazine co-founder and author Shawn Perich passed away on August 3 after a courageous battle with glioblastoma brain cancer. Not only was he an amazing writer, but he was also an avid outdoorsman and a fierce advocate for conservation. Shawn made a big impact in the outdoor and editorial community, and he will be greatly missed. Thank you to our sponsors for helping us honor Shawn and the influence he had on so many people. He was truly one-of-a-kind.

If you are interested, please consider donating to the Shawn Perich Memorial for Glioblastoma Research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester.

Fishing Adventures, and Misadventures, with Shawn

By Sarah Ferguson

I met Shawn in the spring of 2019. We became fast friends based on our shared love of fly fishing and trout. We quickly realized, after a couple multi-day North Shore steelhead outings, that we had a compatibility that’s not always easy to find with other anglers. In the short time since then, we managed to fit in a lot of campfires, laughs, discussions, adventures, some misadventures, and most importantly, time on the water. Eventually we built, not just a fishing partnership, but, a close friendship.

Our dogs, Frank, a pug, and Rainy, a Lab, were also good pals and loved getting out together on our fishing and camping trips. Frank seemed to get ‘big dog energy’ whenever he would hang out with Shawn and Rainy. One time, Frank disappeared off the island I was fishing from, which seemed impossible since he will go out of his way to avoid puddles to stay dry. To my surprise, I saw Shawn and Rainy crossing the river and a tiny pug bringing up the rear. Frank had braved the water to follow his buds.

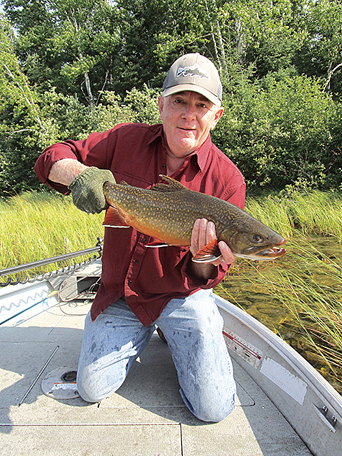

One of my favourite trips with Shawn was on the Nipigon River in the summer of 2019. It involved my personal best, a 25-inch brook trout, and an unexpected encounter with some kind strangers. Shawn wrote about it in a September 2019 Northern Wilds article, so I will save you the details here and let you refer to his more eloquent and engrossing account of the story. One part he left out, though, was how he temporarily became a wanted man by the Nipigon police. He realized while we were fishing that he had filled up with gas that morning but forgot to pay. As soon as we arrived back to Nipigon that evening, we went to the gas station to settle up. It turned out they had called it into the police that morning, who had been out patrolling, looking for his truck. So, our next stop was the police station to clear his name! We had a good laugh about that one.

Another memorable trip was in the fall that same year. We’d headed out with hopes of coho or early fall steelhead. After two days of fishing, all we’d managed was a single coho. As a last effort, Shawn wanted to try the mouth of the Steel River. It was quite windy when we arrived, waves crashing against the shore and pushing water up-river. I wasn’t feeling very hopeful at this point and decided to sit this one out with the dogs on shore. Shawn marched out, thigh-deep into the surf, and began casting a streamer fly. Within a few casts, he had hooked into the most perfect, chrome steelhead. It was a perfect ending to our weekend.

I will miss our adventures greatly, but I will cherish the memories we made in the short time we had.

Thank You for the Memories

By Elle Andra-Warner

Many years ago—a short time after Northern Wilds published its first issue—I received a phone call from Shawn Perich, asking if I’d be interested in writing for the publication as their Canadian feature writer. My answer was yes—and it was the start of a long friendship with Shawn that lasted until his passing.

At the end of each month, Shawn would bring the latest issue to our place (in Thunder Bay) for distribution in the region. Sitting around our dining room table, we’d have interesting conversations—sometimes debates—about an eclectic mix of topics: from writing and story ideas to life, family, fishing, and yes, occasionally even politics. We talked about the latest news, life’s challenges, and world situations (we didn’t solve any, but had fun discussing them). We laughed at funny stories and jokes (he chuckled at my trouble in ‘understanding’ jokes), and we shared both happy times and not-so-joyful happenings in our lives.

He had a wonderfully keen sense of humour and a mischievous side to him. Like the time he brought me a big ‘gold star’ for getting my story to the editor by deadline, something that was rare.

Shawn’s late life-partner Vikki would sometimes come with him to Thunder Bay, as well as his co-owner Amber Pratt. At times, I’d make a dinner meal; other times we’d head out to a restaurant. And seven years ago, it was an unexpected honour to have Shawn drive up to attend my surprise birthday party.

Shawn was always supportive and offered opportunities to expand and grow as a journalist and author.

He fought a strong battle in the last few years. Rest in peace Shawn, and thank you for the great memories.

Eternal Echoes: Sensing Shawn’s Guiding Presence

By Eric Chandler

After Shawn’s surgery, my wife Shelley made him some food. We brought it to his mom’s house in Duluth where he was staying. We talked in the kitchen and I stole glances at the scar on the side of his head. He said the doctors were optimistic. When I think of that moment, I realize I only saw Shawn in person a handful of times over the 17 years I knew him.

When you’re near the ocean (or in our case, Lake Superior) you might not be able to see it, but you can sense where it is. I always knew Shawn was up there in the Arrowhead, just like you know the big lake is there through the trees, even when it’s out of sight.

Northern Wilds had a 10th anniversary celebration in Grand Marais in 2014. I had already been writing for them for seven years and it was the first time I met him. I stopped by the Northern Wilds office a few times on my way to some outdoor activity and saw him. He convinced me to join the Outdoor Writers Association of America. I hung around with him for a few days at the OWAA annual conference that was in Duluth in 2017. I went to a couple editorial calendar planning meetings where his team treated me like a family member, even as a freelancer. Those were all the times I looked him in the eye. The rest of the time, he was like a voice in my head emanating from somewhere in the woods.

Shawn and Amber got ahold of me when I only had a dozen articles to my name. Since 2007, they’ve published around 100 of my pieces in Northern Wilds. They gave me room to grow and become a better writer. Shawn challenged me to learn new things, like how to write journalistic pieces in the third person, where the story was more important than my presence in it. He let me write a beer review column for a year. (I wrote off beer on my taxes. Ha!) I learned how to interview people by talking to the brewers. He asked me to write a column for Veterans Day, which was a little out of the box for his publication. They let me write a piece that teased the reader for being an “industrial tourist” in a magazine designed to be read by tourists. I once read that writing can’t be taught, but it can be learned. Shawn and everybody at Northern Wilds let me learn for almost two decades.

By some miracle, three years ago, I was wise enough to thank Shawn directly for everything he’s done for me. It was via email, so yet another time where I didn’t see him in person. But now, as before, he will be a presence like Lake Superior out of view past the trees. I can’t see him, but I can sense he’s there.

Minnesota Dreams: A Journey Inspired by Shawn Perich’s Words

By Chris Pascone

I first got my hands on Shawn Perich’s books through interlibrary loan. I was 13, maybe 14 years old. Minnesota was a long way away from my tiny western Massachusetts town, and I was going through a wicked phase of fantasizing about cold-water lakes, snow-covered backcountry ski routes, and sublime North Shore brook trout that could be found precisely in Shawn’s world. I had Minnesota Fever, and Shawn was to blame.

Shawn’s books kindled my deep interest in all-things Minnesota when worn-out New England just wasn’t cutting it for me. His writing brought me to a place where wilderness was real, where fish and game were a part of daily living, and a person could thrive in tune with wild nature.

First it was his book The North Shore: A Four-Season Guide to Minnesota’s Favorite Destination, published in 1992. I was determined to learn more about this idyllic midwestern place, and Shawn’s writing beckoned me with his realistic descriptions of gigantic Lake Superior, its oversized fish, and the adjacent wilderness. I was longing for a place where life could unfold in wild places, and Shawn had my number. He made good outdoor living so real, so tangible, so worthwhile. Shawn’s writing, along with the Piragis mail-order catalog, and the Twins’ two World Series victories, got me through some tough teenage years. There was something different out there in Minnesota that I could hope for, strive for, and dream about.

As the years went by, Shawn kept writing more books that transported me to these better, wilder places. His Fishing Lake Superior: A complete guide to stream, shoreline, and open-water angling had me drooling on every page. Coho salmon? Steelhead trout? Shawn knew all about how to catch them, and I was a wannabe. His vivid descriptions made catching these rare fish seem downright likely. I was hooked.

Then came his seminal Backroads of Minnesota, with stunning photography by Gary Alan Nelson. The book literally made the entire state seem like an endless adventure waiting to happen, a land of milk and honey where getting lost in the middle of nowhere was a worthy goal.

Then the poor Minnesota librarians shipped a copy of Shawn’s Wild Minnesota to my hometown library. It was another Perich bullseye fired at my East Coast disillusionment.

The interlibrary loan folks were racking up the miles on these cross-country book deliveries. Finally, I released them from their misery and moved my whole family to Duluth in 2014. We hit an incredible jackpot here—it was just the way Perich wrote it up. I’m proud to say I eventually got to meet my literary hero in person, and even got the pleasure of visiting him at his home in Hovland.

Shawn showed me his canoe that day, and discussed with me the rowing mechanism he had installed to make it easier for him to handle the canoe solo while fishing. I couldn’t believe I was standing there in his driveway, talking canoeing with the man himself, observing the very writer who had done so much to give me a dream to follow in life.

Thank you, Shawn.

Reflections on Shawn Perich

By Joe Friedrichs

Shawn Perich thought I was a bit of a prick. It was part of our professional relationship, you might say.

I would brag about all the big fish I’d been catching, or how I scooped Minnesota Public Radio or the Duluth News Tribune on an important story “once again,” and Shawn would typically respond with either a blank stare or a causal shrug of his shoulders. “Okay,” he would nonchalantly say.

Perich and I didn’t always see eye to eye on a variety of issues, but I wouldn’t be fishing across the Northern Wilds, or a journalist and writer making a living here, without his help. He gave me an opportunity when I had little credibility to lean on in this region, at least in terms of knowledge of the area. In 2013, I showed up on the Gunflint Trail with few connections. I knew how to fish and I’d published some newspaper articles in Montana and Oregon. That was it. That’s what I arrived with.

During the winter of 2014-15, Perich asked me to write an article about the dwindling moose population in Minnesota. It was to be a cover story of sorts, a 2,000-word news feature that took time to research and put together. “This won’t be easy,” Perich told me.

He gave me a chance on a big story and I delivered the goods. About a month later, a woman named Deb Benedict sent me an email. She was the station manager at WTIP at the time and was looking for a news reporter to join the station. It was the article about moose that Perich assigned me that put me on WTIP’s radar. I was hired at WTIP a couple months later. I’ve been making a living as a journalist here ever since. It all ties together.

I only went fishing with Perich a few times over the years. Fishing alone is something we both found rewarding. The act of going fishing—loading up the gear, driving to the spot, walking in, listening, casting, hoping—is more important than catching fish most of the time. It is for us, anyway. You don’t need others around, rambling on. And you don’t always have to bring home fish. Perich understood this.

When it came to his writing and reporting, I appreciated Perich’s use of the short quote. He knew how to keep things sharp on the page. Narrate, report, explain, drop a short quote. He was brilliant with this technique.

About two years before he passed away, Perich walked over from the Northern Wilds building to the community garden at WTIP. That afternoon, I was tending to (stealing) some tomatoes from a friend’s plot in the garden. Shawn and I talked some local politics, and then the conversation changed to fishing.

“I’ve been nailing them at this lake,” I told him, naming the body of water.

“You talk too much, Joe,” he said. And then he walked away.

Lessons from the Land: A Tribute to Shawn Perich

By Julia Prinselaar

I caught my first brook trout with Shawn at the granite-slabbed mouth of the Mackenzie River. I’ll never forget that day, but I wouldn’t call myself a natural angler.

After a half hour of practice casting on the beach, Shawn deemed me “ready” to try fly fishing farther upstream. No later than my second cast did I get a bite.

“Fish on!” I exclaimed, struck with that instant rush of adrenaline that all anglers know and love. By then I was so focussed that everything beyond my immediate surroundings had completely dissolved. Shawn was somewhere in the background watching, observing.

Removed from its habitat, the brookie’s pink, orange and blue halos of skin caught flickers of sunshine as it danced above the water. Being so green I hadn’t rehearsed how to land this lively creature, so I simply started reaching for the end of the line to get after this fish. But this fly rod—it was so long, so delicate and flimsy that I was nowhere near the trout—it felt miles away. In desperation I began moving my arms along the length of the rod, going hand over hand until I finally reached my catch.

As it dangled from my line, I proudly turned toward Shawn, searching his face for a reaction. He was bright-eyed and smiling, and so I smiled back. Then both of us turned to the rest of the rod and reel which lay completely abandoned in an eddy, bumping between some rocks and swirling toward the rapids. My excitement switched to surprise and then sheer dismay as both of us tried to salvage his precious, eye-wateringly expensive gear. While I babysat my catch and fiddled with pliers to remove the hook, Shawn calmly waded into the water and retrieved his rod. He never did tell me what the damage was. And he didn’t scold me for my unwitting behaviour, either. Instead, he chuckled in a way that reassured me I hadn’t done anything wrong. In his mind perhaps I had done everything right.

Shawn probably enjoyed that day as much as I did. Not because he caught any fish, but because of the way I lit up with unbridled delight when I landed and later released that trout.

That is the way of mentors. They speak through their actions to the greater purpose of humanity’s existence, as people within place. When I ask myself, what is the older generation’s role for younger people? How must they carry the weight of their experience? It’s a complicated question considering the current state of our planet, but the answer can be simpler than we think.

Mentors like Shawn show us how to live with the land in a good and meaningful way. They pass down their skills and observations to those who come after them, in the hopes that we watch and listen and learn. They facilitate rites of passage that have become somewhat muddled and even forgotten in the context of our modern world, but are no less valuable than they’ve ever been. Together, we’ve inherited a duty to uphold the greatest law in nature: to live in reciprocity. For all that we take, we must give back.

As a devoted conservationist and advocate for public lands, Shawn understood the importance of being a set of eyes, ears, and a voice for the Northern Wilds. For its sake and for ours.

As David Suzuki puts it, “Without a sense of wonder, we don’t have that sense of obligation or responsibility” for the natural world. In turn, our species is culturally and spiritually richer for it. We have people like Shawn to thank for that.

A Story in Wood

By Sam Zimmerman

Shawn and I first met sitting outside of Northern Wilds office with Amber and Breana, after my completion of a public art project for downtown Grand Marais. Our conversation that day was about art, authors, nature conservation, Indigenous representation, and the beauty of the North Shore. I shared my own experiences and what had brought me back to Minnesota after so much time away. What began as a conversation on a beautiful day led me to accept the invitation to contribute a monthly column, Following the Ancestor’s Steps, where I would share my paintings and the story alongside in English and Ojibwemowin.

I had only been home for about a year and a half when I decided to purchase a home and build a studio in Duluth. During the Covid pandemic, many people were doing home projects, leading lumber prices to soar. I posted on Facebook that I was looking to salvage wood from the North Shore that I could use to build my library and shelves in my home office. Not even an hour had passed before I got a call from Shawn, asking me if I would be interested in coming to his home to help him remove old shelving. He said that I was welcome to any wood that I wanted for my own renovation projects. I was grateful and appreciative of the offer.

A few weeks went by and I was finally able to assist him. As we worked side by side, we swapped stories and jokes. I shared what fish or animals I was currently painting, and we talked about the quality of craftsmanship that we were now dismantling. After several hours of work, we had the shelves down and disassembled, only to realize that the pieces were too long for my own vehicle. Shawn offered to bring them down the following week, as he was visiting his mother in Duluth.

Shawn was one of the first visitors to my new home. After we unloaded the wood, we toured the studio construction in progress and he offered me tips and recommendations as a new homeowner. He was generous with his time, stories, and friendship. After he left that day, I would keep him updated on the studio construction. When the bookshelves and cabinets were finally completed, I sent him pictures of the gifted wood, which had housed his own books and now housed my father’s books that I was gifted. Of course, he knew right away that I did not build them, but hired a master woodworker to get them just right.

In such a brief time—a matter of a year or so—Shawn shared so much without hesitation. His absence from the North Shore communities will be felt by so many who, I am sure, also enjoyed the gift of Shawn’s teachings.

Minawaa gigawaabmin Niiji.