During the Victorian Era, it was still the norm that non-native women didn’t do northern wilderness travelling on their own for pleasure. But Minnesota’s adventurer-explorer, author, artist, self-taught botanist and ethnologist, Elizabeth Taylor, bucked society’s expectations. At age 32, she began a lifetime of solo travelling as a tourist, beginning in the summer of 1888 when she went on a 13-day canoe trip on the Nipigon River to McIntyre Bay on Lake Nipigon.

Described as a “soft-voiced, frail, bespectacled small woman,” her lifestyle certainly didn’t match the stereotype. In 1892, four years after the Nipigon trip, Elizabeth became the first non-native woman to travel as a tourist down the Mackenzie River system (Canada’s longest) to the Beaufort Sea in the Arctic, a difficult three-month journey that earned her a spot as the only woman on the U.S. government’s 1908 list of Arctic explorers. A year later, she was the first English-speaking woman to travel over the remote mountain plateau Hardangervidda in northern Norway, the largest such plateau in Europe. In 1895, she visited Iceland for 10 weeks and later stayed a total of 10 years on visits to Denmark’s desolate Faroe Islands in the North Atlantic Ocean between Scotland and Shetland Islands (five of those ‘marooned’ there 1914-1919 during World War I). Besides sketching, making notes, collecting plant and fish specimens for notable museums like the Smithsonian and Oxford, and writing essays on nature, folklore, rituals and culture, she wrote travel articles about her journeys that were published in American and British publications.

It wasn’t until 1920, at age 64, that she gave up the traveling life and returned permanently to the U.S. Four years later, she built a primitive, two-room log cabin home at Wave Robin, North Hollow, Vermont, where she died on March 8, 1932 at age 78.

In 1948, her great-nephew James Dunn Taylor, a former librarian at the Minnesota Historical Society (MHS), obtained the large archival collection of her articles, notes, journals and letters. In 1997, he edited 39 of her travel articles into a 309-page book, “The Far Islands and Other Cold Places: Travel Essays of a Victorian Lady,” which won the 1998 Minnesota Book Award for Personal Papers.

Elizabeth was born on January 8, 1856 in Columbus, Ohio as the fifth daughter of Chloe Langford and lawyer James Wickes Taylor. That same year, the family moved to St. Paul, Minnesota. In 1870, her father was appointed the U.S. Consul in Winnipeg, a position he held until his death in 1893 (he was confident that Canada West would eventually join the U.S.) He couldn’t afford to bring his family to live in Winnipeg (then a village of 100), so the family continued to live in St. Paul while he lived in Canada. Called by friends a ‘vagabond spirit’ who loved nature and the northern wilderness, he often took Elizabeth with him on trips throughout Canada, Minnesota and Washington.

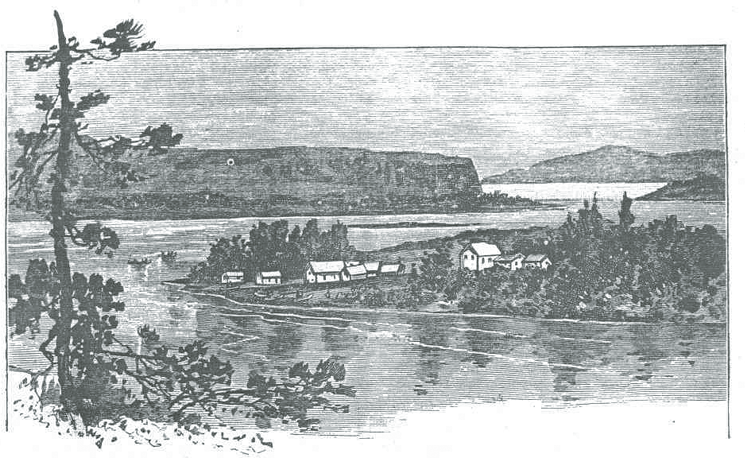

In the summer of 1888, Elizabeth tackled her first solo wilderness venture. After her father used his Hudson Bay Company (HBC) contacts to arrange for travel arrangements, Elizabeth arrived at HBC’s Red Rock House at the mouth of the Nipigon River, ready to start her canoe trip. It would be a trial run to see if she could handle the rigors of wilderness travel; her goal was a Mackenzie River trip to the Canadian Arctic in 1892.

From Red Rock House, she walked a mile alone in the bush to join up at Lake Helen with her canoe companions. Their destination was the Anglican Mission on McIntyre Bay on Lake Nipigon.

“I was about to start on a canoe trip of 120 miles in a birch-bark canoe with perfect strangers, with Indian guides to paddle us,” she later wrote, the strangers being the Anglican missionary’s wife Mary Renison, her young son, her First Nations servant and two First Nations guides. They’d all be travelling in one canoe, loaded with cargo and people. “I looked over the lake we were to cross, where the waves were running high with a strong north wind and climbed down the bank and into the canoe with the calmness of despair.”

For the next 13 days, Elizabeth in her “rough camp-dress” slept in a tent; trekked over 18 rough, stony portages (longest was 2.5 miles); fought heat, fog, rain, sudden storms and big waves on the lake; faced hordes of black flies and mosquitoes; braved fatigue; caught her first trout with a fly-rod; took notes on plants, birds and fish; and enjoyed the, “banquet fit for gods and men: bacon fried with onions, and eaten from a tin plate with an uncertain steel fork.” And she did something few men had dared to do—she successfully ran the dangerous Victoria Rapids which most opted to portage.

Later, she wrote a friend in Cincinnati about the Nipigon trip, “I am proud of the fact that I successfully accomplished the longest trip by a fisherwoman on the river at the time and saw the beautiful Lake Nipigon. I had a perfectly beautiful time; I never spent a happier 13 days in my life.”

Elizabeth Taylor Runs the Victoria Rapids

Elizabeth’s great-nephew compiled this book. | Submitted

The guides were to take down the canoe that morning, to load it for the homeward trip, and soon after I lost my fish we started for the camp. They stopped at the head of the portage, for me to land, and I was about to step out of the canoe, when Joseph said, “You would not like to go down the rapids with us?”

“Is it dangerous, Joseph?” I asked.

He hesitated a moment, and then replied, “The gentlemen do not often run these rapids; sometimes they go down near the shore.” Then after a moment, “We will be careful, if you feel that you would like to go down with us.”

I thought a moment, looked at the rapids running white below us; then, turning to the waiting guides, “I’ll go down, Joseph”. He gave a nod of approval, said a few words in Indian to the under–guide, and pushed off from shore to the middle of the stream. I settled myself in the bottom of the canoe, grasped the thwarts firmly and wondered if I was very foolish. I had a curious sensation as the fierce current seized the canoe and I felt there was no going back. The canoe reared on the edge of the big rapids, seemed to pause an instant, trembling on the brink and then came a dizzy downward plunge; then we rose to a fierce struggle with the waves, the canoe pitching and tossing to and fro, the guides silent, watchful, guiding it with quick, powerful strokes. It was over in two minutes, we floated swiftly down past the camp, and as I drew a long breath and sat up straighter, Joseph smiled with a satisfied air…”

Elizabeth Taylor’s, “Up the Nepigon” (online Nipigon Museum Blog). Originally appeared in Harper’s Monthly, 1889.