What does it mean for art to be a conversation? While many artists have made their mark on the Northern Wilds region, one who stands out is Hazel Belvo. Belvo is an artist, art educator, and women’s art advocate whose art career has spanned over 60 years. Her work has made a lasting impact for women and for the Cook County artist community, and her paintings continue to open up conversations about life, love, nature, and this beloved corner of the world.

Hazel Belvo grew up in rural Ohio and began her career as an artist by training as a classical portrait painter. She studied at Dayton Art Institute, the New School for Social Research in New York, and Harvard University. She first came to the North Shore in 1961 with her then-husband, abstract expressionist artist George Morrison. Belvo recalls being struck by the energy of Lake Superior and its similarity to the ocean, and it was on this visit that she would take a deeply moving visit to Manidoo-giizhikens (the Little Cedar Spirit Tree) in Grand Portage. That visit began what would become a multi-decade artistic exploration for Belvo, fueled by both her innate connection to trees and her training as a portrait painter. Her depictions of Manidoo-giizhikens would go on to garner wide recognition, connecting with viewers across the country and becoming the work for which she’s best known.

“When you’re trained as a classical portrait painter, you know that painting isn’t just a matter of capturing the likeness, but of developing the personality, character, and history of the subject. Having started painting the tree in the 60s, I developed the tree as a personage in my works,” Belvo said. “A portrait painter considers how the viewer receives the image, and the psychology of that is foremost in my mind through all my different bodies of work.”

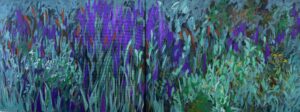

This idea of relatedness—between subject and artist and viewer—is a hallmark feature of Belvo’s work. It is certainly possible, she said, to approach nature as an object, and to therefore portray it as mere imagery. But through the eyes of a portrait-painter like Belvo, a tree—or fireweed, or flowers, or any other natural element—is not a mere subject, but an ever-changing entity with its own energy and life. From this perspective, one can greater appreciate her decades-long studies of the same subject, and better understand her work not as mere depictions, but as taking part in a conversation.

“Every time you approach a subject, it’s changed and you’ve changed, which makes it new,” Belvo said.

While the theme of conversations manifests in Belvo’s nature-inspired work, including her portraits of Manidoo-giizhikens and her Honey Locust series, it’s a broader theme that shows up in her art in different ways.

In 1985, Belvo met her now-partner, philosopher and painter Marcia Cushmore, at the Grand Marais Art Colony. Though they have shared their lives for over 30 years, they had never collaborated on an art project. That is, until Covid arrived in 2020. Like almost every household was during that time, Belvo and Cushmore’s lives were seismically shaken by quarantine. However, this strange period turned out to be a catalyst for a new kind of conversation between the two: a conversation between two artists in paint.

Belvo found painting to be a lifeline during quarantine, and took to painting classical still life, an art form she had not explored since she was a student. An abstract painter and colorist, Cushmore began responding to Belvo’s paintings with her own pieces, using the still life as inspiration but delving into abstractions and bringing her own unique style and perspective. Each pair of paintings—Belvo’s still life and Cushmore’s abstraction—together formed one work, a work that bore both the individuality and unity of its creators. JUXTAPOSITION was displayed at the Johnson Heritage Post in 2021.

On her drive to keep creating, even throughout busy and challenging seasons of life, Belvo said, “I believe mark-making is one of the most unique things a person can do, because every mark that you make is unlike any other mark. How you choose to make that mark and what it says is a path to understanding oneself, which is one of the big issues in life—to know oneself.”

Looking ahead, Belvo is continuing to make new marks and continue conversations through art. Her current project is called Croftville Road. For those unfamiliar with Cook County, this lakeside road is a favorite promenade for locals and visitors alike. Belvo’s project was inspired by the many walks she’s taken on that road with a walker, something that changed her perspective and caused her to look down and notice things she hadn’t before. The 12 paintings will share the story of the road through each month of the year. It’s a project Belvo hopes to finish this summer.

“I see the North Shore as a place of wholeness, and it’s been a very important place of reflection and rejuvenation in my life,” Belvo said.