The world seems somewhat surreal these days. Everything looks normal—home, streets, stores, Lake Superior, lake freighters, cars—yet there’s been a dramatic shift in our day-to-day living. The current global coronavirus pandemic has brought us long lines to get into some grocery stores; six-foot (2 metres) social distancing; closed schools, restaurants, theatres and international borders; curbside pickups or delivery of groceries/food; wearing masks; stay-at-home orders; and, the like.

We remain however plugged in to the world, family and friends with our cellphones, computers, social media, TV, and 24-hour news broadcasts with pandemic updates. A century ago, during the 1918-20 global influenza (H1N1 virus) pandemic, there were no such devices, so how did people connect or call out for assistance?

In our Northern Wilds, one of the legendary stories from the 1918-20 pandemic involved the 50-mile (72.3 km) snowshoe journey for help by Ojibway Chief Blackstone and his wife to Winton, Minn. from their Sturgeon Lake Band (SLB) community, Reserve 24C. Their village was located at the mouth of Wawiag (Kagawagamuk in Ojibway) River where it enters Kawnipi Lake at Kawa Bay in the eastern half of Ontario’s Quetico Provincial Park. (Chief Blackstone of the Sturgeon Lake Band was the son of the first Chief Blackstone of Lac La Croix First Nation, a famous orator who fought for the rights of Ojibway people in the 1873 Treaty 3 with Canadian government.)

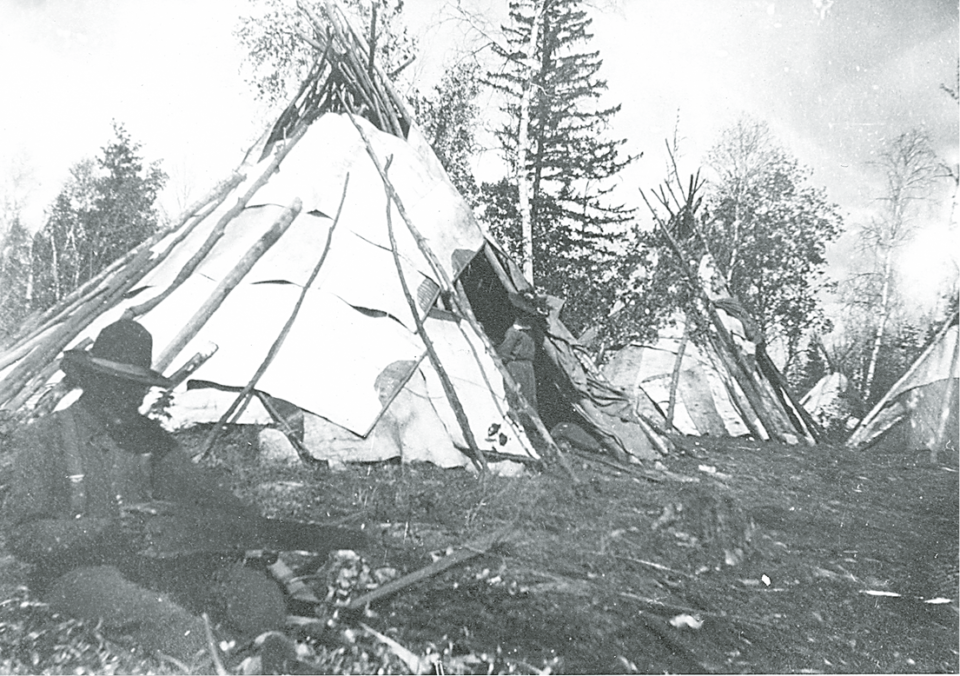

In author John Nelson’s book Quetico: Near to the Nature’s Heart, he writes that the SLB site was established in 1877 by the Ontario government after the region’s nomadic Ojibway, part of the Ahnishinaabe Nation, were asked to select an area for their reserve. Government records indicate their population was about 52.

While no universal consensus as to its origin, the 1918 influenza outbreak was tagged the “Spanish” flu as Spain was the first country to publicly report on it. Lasting for two years in four separate waves, it ended in the spring of 1920. During that time, more than 50 million people died worldwide. It wasn’t until the 1930s that scientists confirmed it was a virus, not bacteria. In the U.S., the pandemic resulted in more than 675,000 deaths; in Minnesota, more than 10,000; and Canada, about 50,000 deaths.

On the website of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it notes that since there was no vaccine over a century ago to protect against the 1918 influenza, “control efforts worldwide were limited to non-pharmaceutical interventions such as isolation, quarantine, good personal hygiene, use of disinfectants, and limitations of public gatherings, which were applied unevenly.” Sound familiar?

In the winter of 1918-19, the pandemic was decimating the village at Kawa Bay. In her book Walking the Old Road: A People’s History of Chippewa City and the Grand Marais Anishinaabe, author Staci Lola Drouillard writes that only Chief Blackstone (the second) and one of his wives “were healthy enough to snowshoe to Jack Powell’s cabin on Saganagons, in order to get help.” As the story goes, there was no telephone or radio there, so the two continued on to Winton, Minn., where they radioed the Canadians that their village at Kawa Bay was dying.

The message relayed, the Chief and his wife headed back up home. Then, tragedy struck. At the northeast end of Agnes Lake, Chief Blackstone collapsed and died. His wife pulled his body to shore, wrapped the Chief in a rabbit skin blanket and buried him in the snow. “Chief Blackstone’s body was later retrieved by his people and buried at the site of his former village on the shore of Kawa Bay,” wrote Drouillard.

It wasn’t until spring when the Canadian authorities responded to the call for help. By the time they arrived at Kawa Bay, only a few people had survived and they were moved to Lac La Croix to reside.

Nelson wrote in his book that the 1918 influenza outbreak “may well have been the final event of a band whose population had shrunk to just a few families due to earlier outbreaks of disease.”

It should be mentioned that when Quetico Provincial Park was formed in 1913 it surrounded the Sturgeon Lake Band’s village. Two years later in 1915, without consultation with the Indigenous people or compensation, the Ontario government cancelled the reserve of Sturgeon Lake Band at Kawa Bay.

Nelson writes, “When government terminated Reserve 24C in 1915, the long history of the Ahnishnaabe people making the resource-rich mouth of Wawiag River their home came to an official end.”

Seventy-six years later, on June 3, 1991, the Ontario government made a formal public apology for the injustice of taking away the reserve and forcible removal of the Sturgeon Lake Band 24C.