Ask someone where they got their chairs and my bet is that seldom, if ever, will anyone respond that they came from such and such trees. That would sound silly, unless, of course, you’ve noted the trend in the food industry to name the orchard, the apiary, or the plot of ground from which a menu item was “sourced.” Few of us can identify the wood from which our wood products were made let alone the forest or plantation from which the wood was harvested. We say instead, if asked, “That chair was my grandmother’s” or “We bought them in a secondhand store,” or more often the answer is simply “Ikea.” in the case of the handmade Windsor chairs that I specialize in, it takes a forest to build a chair. Lest you take me too literally, not an entire woodlot to make a single chair, rather a variety of species.

Windsor chairs are an interesting example of engineering in which a lot is being demanded of the wood. The species of wood must be carefully chosen. Windsor chairs are defined by the construction type rather than by the specific chair. The seat is a solid, wide plank of wood with holes drilled to accept the legs. The back is socketed into holes drilled into the seat and stretchers are socketed into the legs. All the joinery on the Windsor chair is round tenons into round holes. This makes for a chair that can be made using simple hand tools with readily available materials from the local woods.

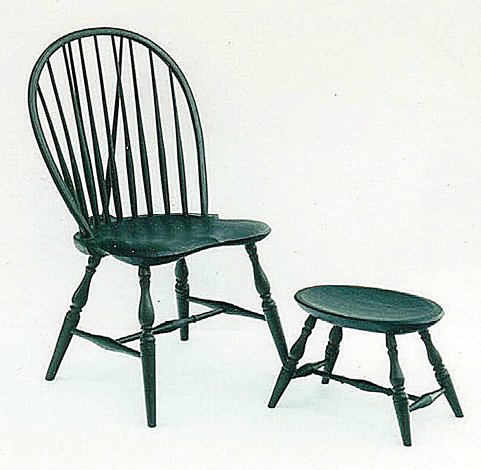

As Windsor chairs became wildly popular in this country by the end of the 18th century, they evolved to a uniquely American style, with or without arms, and various configurations of chair backs, some with complex bent parts. Most Windsor chairs have turned legs, stretchers and arm posts lending to distinct regional variations and styles specific to the maker. What all handmade Windsor chairs share in common is a design engineered to be strong yet flexible and lightweight. To accomplish this, handmade Windsor chairs are made from different species of wood for different parts of the chair, depending on the demands of that chair part. The beauty of a Windsor chair is in the silhouette as opposed to the color or grain of the wood.

Although available species vary from one place to the next, the wood of choice for chair seats in North America is eastern white pine (Pinus strobus), prevalent across a range of climates along the east coast westward to the Great Lakes. This species has, since earlier times, been prized for wide, clear planks which are easily sculpted into a commodious seat. It has greater stability than most other northern Minnesota coniferous species. Basswood (Tilia americana) has similar characteristics and is also well-suited for carving seats. It’s common across the northeastern United States and has the further advantage of being stronger than white pine.

While both of these woods make for a good seat, they are too soft to meet the demands of the chair back, which is called upon to withstand the forces of not only the user leaning back in the chair but also twisting and turning. For the chair back, the best woods are stringy and tenacious. Having the capacity to bend, these woods flex under use but also respond well to steam bending, readily assuming the complex shapes required of the continuous armchair and bow-back designs. Good choices for chair backs are ash, either Fraximus negra or americana. Hickory is strong, but not common to northern Minnesota. While northern red oak (Quercus rubra) meets most of the criteria, my personal favorite is white oak (Q. alba) or the subspecies more commonly found in northern Minnesota, bur oak (Q. macrocarpa). Bur oak has strength with enough flex to resist breaking and takes well to steam bending.

Stringy and tenacious species present difficulties when turning legs, stretchers and arm posts. Windsor chair designs were first developed at a time when lathes were human powered, the spring pole lathe being the tool of choice for early chair builders. (Modern lathes have evolved with enough weight and horsepower that in combination with modern abrasives just about any wood can be forced into a chair leg.) Because chair legs are thicker and stiffer, they don’t require the stringy toughness of the chair back. The most sought-after woods for turning possess creamy smooth grain. Choices in northern climes include primarily birch (Betula papyrifera) and the maple family (Acer). Birch is more readily available; maple has the advantage of being somewhat stronger.

By carefully choosing wood which meets the specific demands of each part of the chair, a chair can be built of locally harvested materials using traditional tools and methods. Ask me where my chairs come from and I’ll source for you the exact location of each ash swamp, pine stand, or logger’s landing.

By John Beltman

John Beltman is a lead woodworking instructor at North House Folk School, where traditional craft is taught on the shore of Lake Superior.