When I was a kid, Portage Creek, located east of Thunder Bay, on the Sibley Peninsula, was a well-known steelhead fishery. I caught one of my very first rainbows at Portage, drifting sponge in the pool located below the falls. This spot was a bottle neck for trout and many thousands of trout were caught there by many hundreds of people over the years. It was truly a fish bowl.

I can recall one Saturday at Portage when I was in my teens. The run was on and there were anglers all over the small creek. In those days (the 1970s) the limit for steelhead was five fish of any size. As I recall, the anglers that came and went from that pool caught and harvested about 70 fish over about eight hours of fishing. At one point, three dozen trout were lined up end-to-end on the bank.

As productive as this fishery was in its day, that kind of harvest was not sustainable. By the late 1980s, the fishery was declining rapidly. Then, out of the blue, the private land that people had been using for years to access the creek was sold. The new owner of that land chose to close the road and the access. As the whole river was generally surrounded by private property, this meant angling all but stopped. While this was not a welcome turn of event for steelhead anglers, it created a unique opportunity.

Enter Jon George, a rainbow-obsessed fisheries technician who worked for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. George had been angling the Portage for decades and saw the change to the fishery. He began to mull over the possibility of doing a study on Portage. A river that had been exploited for decades would be a prime place to do a population study. What would happen if there was no harvest of a wild population of Lake Superior steelhead?

“It was heavily fished back in the late 1980s,” says George, now retired from the OMNRF, but still actively involved in the Portage Creek study. “It was 70 percent total mortality of any spawning year that came in. As a result, the population became very small and very young. The Portage steelhead population was borderline collapsed.”

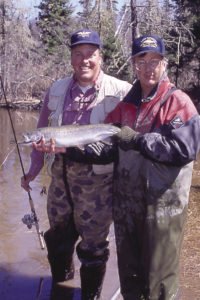

In 1994, with the co-operation of the landowner—and using mostly volunteer anglers from the local steelhead club—George undertook a capture, tag and release study on Portage Creek. Volunteer anglers could fish and tag the steelhead, carefully recording data about each trout and taking a scale sample that was tucked in a small envelope. It was both a ground breaking co-operative venture, and an incredibly successful way to monitor a stock of fish rebuilding after years of over harvest. The results showed quickly.

“Within eight to 10 years, it went from 400 or 500 fish to over 2,000 fish,” says George of the creek. “We allowed survival because there wasn’t any harvest. Those big old spawners do much better spawning and that dramatically increased the population.”

During this period, it was this columnist’s good fortune to be able to join a few tagging sessions. As someone who had fished Portage most of my life, it was incredible to see rainbows packed into the pools and runs like sardines. The spawning areas were dark with fish of all sizes, including some true giants. One wondered if the river could ever possibly hold more fish. Then, 10 years into the study, a strange thing started to happen. The steelhead began disappearing.

“In 2004, we produced a massive bumper crop of little guys, about 900 fish surviving to age three,” says George. “Since that time, our average year class has gone down to eight to 10 fish a year surviving to age three. Something is going on in Black Bay.”

Portage Creek, it should be noted, runs into Lake Superior’s Black Bay. For many decades, the bay was heavily exploited by commercial fishing. Black Bay is unusually shallow and fertile as Lake Superior Bay’s go and it was fished for perch, walleye and pike. Sometime in the early 2000s, commercial fishing began to wind down. After years of heavy harvest, the warm water fishery began to rebound. Walleye are largely protected on the bay and they grew more numerous. A sport fishery developed for perch. The traditional and ancient fishery of Black Bay began to return. At the same time, the steelhead fishery in the Black Bay tributaries was on a precipitous nose dive. Runs of trout on the Wolf, Coldwater and Black Sturgeon rivers dwindled. George says the situation on Portage Creek reflected this change in the bay’s fishery.

“There wasn’t much predation back in the 80s and 90s, because there weren’t many large predatory fish,” says George. “ After 2004, those little guys produced in Portage Creek weren’t surviving any more. They were easy morsels.”

George says using Portage Creek as an index, there is probably a 90 percent decrease in steelhead in Black Bay. Portage itself is a mere shadow of what it was at its peak, and is far worse off than when angler harvest was at its highest level. George says in 2018, just 144 adult steelhead ran Portage Creek. George says they catch more brook trout in the creek now when they are tagging, although he wonders if that is just because there are virtually no rainbows. He says in recent years, they have been lucky if they tagged 40 steelhead during a whole run. That compares to years in the early 2000s when they tagged as many as 900 steelhead in a season.

George says the steelhead have been adapting to the new situation on Black Bay. He says the recent tagging results show changes in which young trout are surviving best.

“The adults that are coming back now in Portage Creek survived from bigger smolts,” says George. “Back in the old days, 80 to 90 percent of the little guys that went out into the lake were age one. Now that’s completely turned around and they are age two.”

George says only time will tell what the future holds for the Portage Creek steelhead—and all the rainbows in the Black Bay watershed. He says any kind of down turn in the warm water fishery in Black Bay would likely improve the fortune of steelhead, but for now, that fate doesn’t seem likely. George, however is not giving up hope.

“I don’t think it will ever come back to what it used to be,” he says. “But I do believe there might be a slight increase. And that’s why we will continue to monitor Portage Creek.”