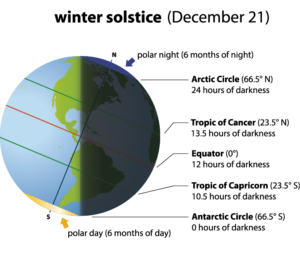

We are in the time of year when many folks leave for work in the dark and come home in the dark. During December, the sun is above the horizon for less than nine hours each day. Daylight continues to decrease until Dec. 21, the shortest day of the year in the Northern Hemisphere and known as the Winter Solstice.

While the pagan festivals associated with northern Europe and ancient Rome are best known, the celestial event also is celebrated by people in North America, Asia and the Middle East. In the southwestern U.S., the Zuni perform dances and ceremonies and feast to celebrate the harvest during Shalako. The Chinese and East Asians gather as families for the Dongzhi Festival to make and eat traditional foods, such as glutinous rice balls, and enjoy time together. Iranian friends and families gather on the longest night of the year to eat fruits and nuts, and read poetry to observe a festival called Shab-e Yalda.

The ancient rituals of northern Europe and Rome remain recognizable in today’s modern America. The Romans had a religious observance for the god Saturn called Saturnalia, which included gift giving, a feast for slaves, drunkenness and sacrifice. Pagan peoples of Scandinavia and Germany had a 12-day midwinter celebration called Yule or Jul, from which were derived modern traditions such as Christmas trees and wreaths, as well as the burning of the Yule log. They believed the sun stood still for 12 days at midwinter. From the ancient Druids of Gaul and Britain comes the tradition of mistletoe as a symbol of fertility, which is why people today stand beneath a cluster of it and kiss.

One constant of all winter solstice celebrations, including Christmas and Hanukkah, is the incorporation of fire and, in modern time, electric light. Since early celebrations, based on the solstice change in the length of daylight, observed the death and rebirth of the sun, light in the dark was, and remains, a powerful symbol. And today, the many lights of a Christmas tree evoke holiday cheer. More recently, some communities and organizations have begun celebrating the solstice with gatherings around a bonfire.

However you choose to observe the solstice, there is a common truth: this is a time for families and friends to meet and enjoy one another’s company.