It is thanks to the shorthand reporters of the ancient past—speedwriters of language—that the world has a record of historic speeches, parliamentary debates, dialogues, and sermons dating back over 2,000 years.

Does shorthand seem like an ancient, outdated way to take notes? Hmm…consider this. Ordinary longhand writing averages 35 words per minute (wpm); people speak at 150-180 wpm. The world record for writing shorthand is a whopping 350 wpm by Nathan Behrin in 1922 during a two-minute test—that’s an incredible writing speed of 5.8 words per second.

But back to historical times. Scribes in ancient Egypt had developed shorthand signs to make their writing faster and more efficient, as had the Chinese during the Han Dynasty (207 B.C.-220 A.D.) and the Greeks in the fourth century.

However, the world’s first recorded shorthand system is historically dated at 63 B.C. when Marcus Tullius Tiro, secretary to Roman orator Cicero, recorded Cicero’s debate on democracy in the Roman Senate. Tiro is credited with inventing a method of rapid writing that became known as Tironian Notes (though some say Cicero deserved credit). Back then, there were no pens or pencils for writing, so Tiro used a stylus with an ivory or steel point to record the shorthand on wax-covered tablets. Tironian Notes used a combination of letters and special symbols, consisting originally of 4,000 signs, later increasing to about 13,000. It was used in Europe up until the 11th century. (Trivia: Julius Caesar, who also used Tironian shorthand, was later stabbed to death with a shorthand stylus.)

Shorthand is a different way of writing English. It’s a symbolic writing method that uses symbols, signs, and/or abbreviations for words and common phrases. One historian wrote “shorthand is one of mankind’s most misunderstood and unappreciated skills often considered old-fashioned,” while another said that shorthand is one of the “world’s disappearing literary languages.”

So, is shorthand old-fashioned and no longer used? Well, shorthand is still used by journalists, professionals, court reporters, and journal writers. The process of writing in shorthand is called “stenography” and the person using it is a “stenographer,” though that term is fading out of use.

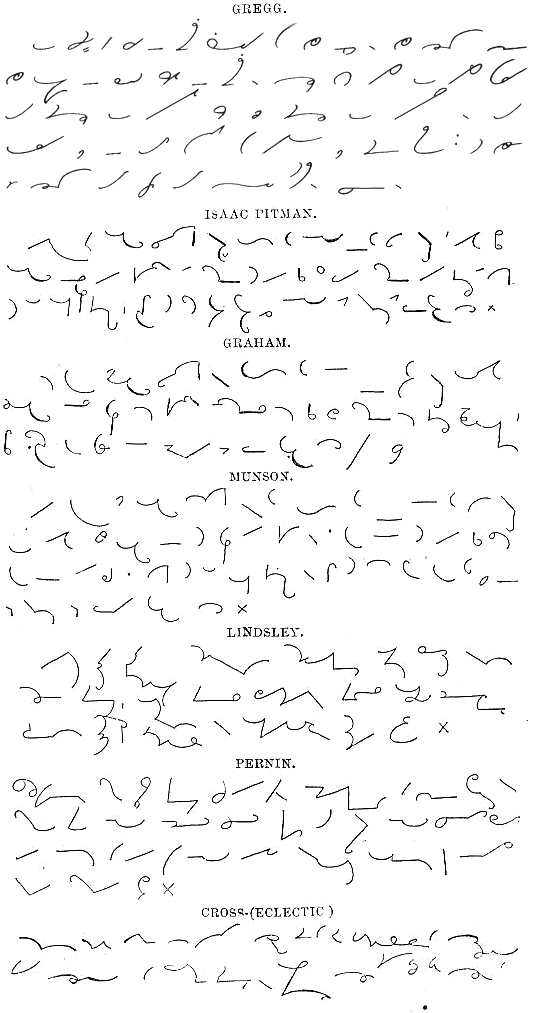

By the 1800s, there were over 70 different methods of shorthand in use. Historical figures over time have used an eclectic mix of shorthand systems. They included Sir Isaac Newton using Shelton Shorthand in his notebooks, and England’s Samuel Pepys used Shelton for his diary entries and official papers (Thomas Shelton’s Short Writing was first published in 1626). Early Mayflower settlers recorded their history with shorthand. Former U.S. president Woodrow Wilson learned Graham Shorthand, developing it into his own version of Graham system writing, baffling scholars trying to interpret his shorthand. It took until 1960 to figure out Wilson’s shorthand he used for his acceptance speech for the 1912 presidential nomination. And author Charles Dickens used a difficult system throughout his life called Brachygraphy, which he called “a savage stenographic mystery,” and for which over the years he invented new symbols.

Shorthand as a secret language works great for love letters, like the ones written by Canada’s former Prime Minister Sir John Sparrow Thompson (1845-1894) in the now extinct Dodge Shorthand, developed by Rhode Island’s Jonathon Dodge in 1823. Thompson was taught Dodge by his father and later Thompson taught it to his wife, Annie. When Thompson resided in Ottawa for his government work and Annie remained in Halifax, the couple would exchange love letters written in the secret code of shorthand.

It was in the 1800s that two men invented what would become the world’s two most popular shorthand systems, both still being taught today. England’s Sir Isaac Pitman (1813-1897) developed what became known as Pitman Shorthand. First presented in 1837, it soon was used in 15 countries. Based on phonetics, it records the sounds of speech using thick and thin strokes, length and position for the consonants and for vowels, short strokes, small dots, or dashes (though vowel sounds are optional). Over the years, different versions of Pitman Shorthand have been created, with the most recent being Pitman 2000. (Trivia: I learned Pitman Shorthand in high school but alas, now I can only write a few words in shorthand.)

Interesting that Pitman’s brother Benjamin “Benn,” who was born in England, later became a U.S. resident to promote his brother’s Pitman Shorthand in the U.S. He became the official stenographer using Pitman Shorthand during the trial of president Abraham Lincoln’s assassin, as well as recording other U.S. prosecutions involving Sons of Liberty and the Ku-Klux Klan.

Shorthand in movies? Apparently, a form of Pitman 2000 was used for the language of the Vogons, a fictional alien race in the movie version of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

The second ground-breaking shorthand system, the Gregg Shorthand, was invented and first published in 1888 by John Robert Gregg (1867-1948). Like Pitman, the Gregg system is also phonetic, recording sounds of speech rather than the spelling. However, it uses thin strokes and lengths for consonants, while vowels are written as hooks and circles on the consonants.

Jumping to the 21st century, shorthand machines—like those used in court rooms now—are replacing the need for hand-written shorthand. But that’s a story for another day.