As I write this on an evening in early February, one of the coldest nights of the year is approaching. The City of Thunder Bay is under an “Extreme Cold Warning,” bringing windchill values to minus 40°C overnight. The risk of frostbite and hypothermia is palpable.

As most people prepare to stay indoors and keep warm during the cold snap, I think about the creatures who inhabit the boreal forest. The thick skins and coats of fox, beaver, moose and deer enable them to survive the harshness of winter through to the longer days and warming temperatures that lie ahead.

At this time of year, in early February, morning temperatures can hover around minus 20°C—exciting times if you’re a hide tanner. Cold weather is favorable for thinning the hide of a thick-skinned animal like a moose to prepare it for tanning at a later stage.

Skins can be thinned throughout the year, but many tanners in northern climates prefer to scrape the hide while frozen. A moose’s hide can be a quarter-inch thick in some areas, so when the skin is frozen, sharp tools are able to shave the skin more easily.

But such a task requires consistently cold temperatures and I have been eagerly awaiting a period of cold weather that lasts a week or more. Instead, early January brought mild and inconsistent temperatures that even climbed above freezing—not nearly cold enough for frost scraping.

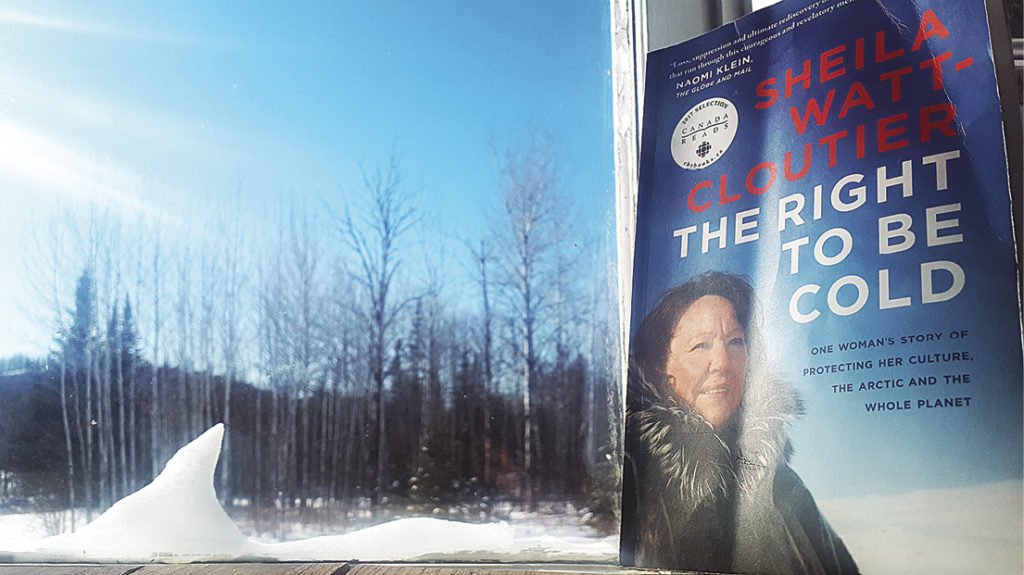

My relationship to winter and the personal excitement it brings reminds me of a memoir written by Sheila Watt-Cloutier titled, The Right to Be Cold. For more than 25 years, Watt-Cloutier has committed her life to speaking publicly about the effects of climate change on the Arctic environment and advocating for the rights of Indigenous peoples in the far north. Through her own experience as an Inuk woman, she documents the loss of traditional skills and knowledge that, in some cases, has occurred in the course of a single generation.

The Inuit are a hunting culture. As Watt-Cloutier explains in her book, values such as patience, endurance, courage and good judgment are all taught through the skills of successful hunting.

“It is the wisdom of our hunters and elders that allowed us not only to live but also to thrive. As you are taught how to read the weather and ice conditions and how to become a great hunter…you learn how to become focused and meticulous, for your family depends on these skills for survival. This is the wisdom our hunters and elders have shared with our children for generations, and this holistic approach to learning is an essential part of Inuit culture,” she writes.

“But this important traditional knowledge has begun to lose its value as a result of dramatic changes to our environment. This wisdom, which comes from a hunting culture dependent on ice and snow, is as threatened as the ice itself.”

In the Arctic and indeed all over the world, the land is inextricably linked to a people’s cultural identity. What happens when their environment is on the brink of irreversible change?

On the Canadian east coast, data from the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans shows that the sea surrounding coastal Labrador is warming at an unprecedented rate. Winter is on average six weeks shorter than it was historically, and the region’s sea ice is about a third smaller than it was a decade ago.

For the people of Rigolet, Canada’s southernmost Inuit community, vanishing ice and unpredictable seasons means they are being forced to adapt in ways they never have before. Shrinking ice packs and changing weather patterns has made travel to traditional hunting grounds increasingly unreliable.

The social impacts of climate change are becoming more visible. Watt-Cloutier recalls several members of her community losing their connection to the land and falling into alcohol abuse and domestic violence.

“I share these stories,” writes Watt-Cloutier, “to show how quickly in my own life, in less than twenty years, the tumultuous changes from the outside were affecting the very core and soul of the grounded, reflective, caring hunter spirit of our men.”

Ashlee Consolo, director of the Labrador Institute in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, echoes her statements.

“The land is not just the land for them. It’s family, it’s kin, it’s part of you. Every aspect of Inuit culture grows from the land,” she writes in The Guardian. “When you’re the first generation that can’t do that anymore, that can’t follow your ancestors on to the land, think about how devastating that can be from a cultural standpoint… These changes are disrupting hundreds of years of knowledge and wisdom and connection to the land. That’s a scary thing for humanity,” Cunsolo said.

One year into the global coronavirus pandemic, and I am more thankful for the Northern Wilds of my home than ever before. The land has given me space to exercise and be socially distant from others when needed. More importantly, I find a deep sense of purpose when I have things to do that connect me to the landscape around me, whether I am scraping moose hide for days on end, planting my garden in the spring, paddling along the coast of Lake Superior or hunting and gathering wild foods. The land is my teacher, my playground, my source of inspiration and spiritual sustenance.

But as a settler who lives in a city and embraces Western customs and values, who was not raised in a hunting or fishing family that relied on wild land for survival, it’s easy to exercise my privilege and take these things for granted. After all, grocery stores with fresh produce are only minutes away. And I join many others in feeling a sense of grief and futility in the wake of a changing climate.

As Sheila Watt-Cloutier says, the world needs to realize that our environments, our communities all around the world are not separate, and that our shared atmosphere and oceans, not to mention our human spirit, connect us all.

“It is imperative to change the dialogue about climate change and the environmental degradation of our planet,” she writes. “This will require us to move how we conceptualize this issue from the head to the heart, where all change happens.”