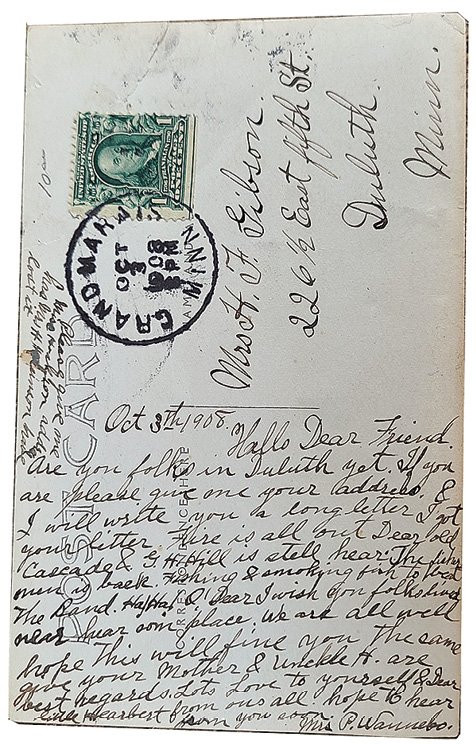

On October 3, 1908, Christina Paulson Wannebo went to Johnson’s Trading Post in Grand Marais and mailed a postcard to Anna Jacobson Gibson. “Are you folks in Duluth yet?” she asked. “If you are please give me your address & I will write you a long letter. I got your letter. The fire is out…. The fishermen is back. Fishing and smoking fish to beat the band. Ha! Ha!”

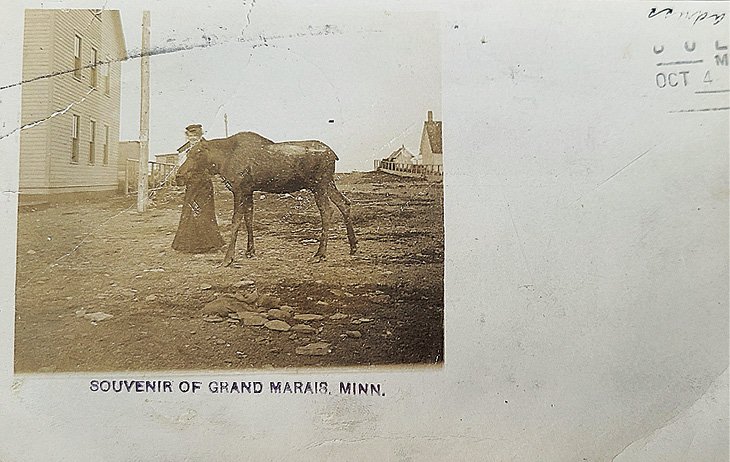

This historic postcard, like so many, has multiple layers to discover and each one contributes to its local and regional significance. The central image of a woman and her pet moose is an early artistic representation of Grand Marais. Then there is the handwritten message that hints at the aftermath of an awful forest fire that devastated the Arrowhead region. The postcard’s circuitous path from Grand Marais to Duluth and back again reveals another dimension of the artifact.

THE PHOTOGRAPHIC CARD

Postcards were, and are, the cheapest and least private way to communicate through the mail. Beginning in 1907, postcards had one side devoted to an illustration, sometimes an original photograph and sometimes a mass-reproduced image. The other side had a “divided back” split between space for a message and space for an address. The lack of privacy and the limited space often made postcard writing predictable and sparse in personal details.

Both public and personal, postcards also advertised for proud towns and aspiring tourist destinations. This postcard depicts Anna C. Johnson and her pet moose in downtown Grand Marais. Born in Arvika, Sweden, Johnson immigrated to the United States in the 1890s. She was an artist and, by 1908, owned a trading post in town with her husband that doubled as the post office. According to local tradition, Anna’s moose developed a taste for tobacco and would walk to the dock to inspect the pockets of arriving fishermen. In this way, the postcard represents the entwined efforts of an art community and a tourist industry that became part of Grand Marais’s identity in the 20th century.

THE MESSAGE

Despite its brevity that typified postcards, Wannebo’s message conveyed important information. Yet those four words, “the fire is out,” understated the severity of recent events in the Arrowhead region that made national news. Three weeks earlier, the New York Times described an apocalyptic scene in Grand Marais. Smoke made breathing difficult. Street lamps burned during daylight hours because the sky was so dark. “To-night the women are kneeling in the streets praying for help, while the men are fighting the flames on the outskirts of the little village,” the Times reported. “Many have sought safety in boats on the lake, and in some instances whole families have pushed out into the waters on home-made rafts.” Four days later, an ominous headline read, “Fate of Town in Doubt,” with the subtitle, “No Word from Grand Marais, Threatened by Forest Fires.”

Grand Marais survived. After a 14-week drought, heavy rain removed the immediate fire threat. “While not extinguished,” the Duluth Evening Herald reported on September 19, “the forest fires are held in check as a result of the storm, and Grand Marais, Chicago Bay and other north shore settlements that have thus far escaped the flames, are considered safe.” By early October, when Gibson reported that the fishermen were “smoking fish to beat the band,” it signaled rapid economic recovery and the sights and smells of normal times. Wannebo must have had more to say about her recent experiences. She knew from experience the desperate choice between braving the fire on land or fleeing the shore on a home-made raft. If the “long letter” that Wannebo promised Gibson survives, it has not yet surfaced.

JOURNEYS

The postcard also connected friends with similar backgrounds and life stories. Both Wannebo and Gibson came to the United States as immigrants from Norway and Wannebo spelled in a way that suggests she picked up English by ear as a second language. Unfortunately, beyond this postcard, the two women left few public clues about their lived-experiences of coming to the United States. Wannebo died only four years later of “Bright’s Disease” at the age of 37 and is buried in Poplar Grove Cemetery just south of Grand Marais. Gibson lived for another six decades. That Gibson kept the postcard suggests a deep and important friendship of which we only have this single artifact.

Old postcards are common but they represent only a small fraction of all the mail that has circulated around the globe. This one probably entered the collectibles market—and got a second life—after Gibson’s death. A handwritten price ($10) indicates the postcard spent some time in an antique store. For collectors, looking through boxes of old postcards can be like scanning Lake Superior’s shore for a rock. The “right” postcard is subjective. The image, the age, the number produced, the stamp, and the message are all variables for a postcard’s value. Purpose also matters. Like choosing the “right” stone, it matters whether someone will skip it across the water or put it in a garden. In a similar way, a postcard can serve decorative, utilitarian, or educational purposes.

What makes a postcard historic is often different from what makes it valuable. When a seller in Stillwater, Minnesota, posted this postcard on eBay in 2019, the sentences about the fire and the fish first stood out to me as important. Then the other layers emerged: the friendship, the trans-Atlantic journeys, and the glimpse into the early 20th century history of Grand Marais. When the postcard traveled to Grand Marais in June 2021, it closed a circuitous path. Now it is back within 500 feet of where it was first purchased and postmarked.