Lake Superior has a lot of fans. Its identifiable shape shows up as tattoos, jewelry, bumper stickers, and more. We hug it with a Circle Tour, we snuggle up close in our cabins and tents, and we gaze lovingly into its crystal clear waters.

Deep, cold, and powerful: We sometimes allow ourselves to believe that The Lake is big enough and strong enough to endure anything we throw at it. Its perceived water quality is part of its allure.

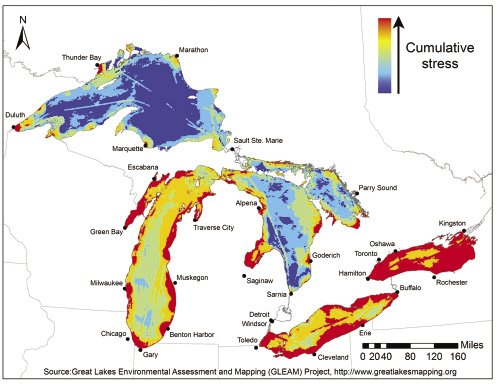

That perception is true, to a point. The Great Lakes Environmental Assessment and Mapping Project (GLEAM) put together a map of all the Great Lakes that shows the cumulative environmental stress caused by 34 factors, including climate change, aquatic invasive species, and nutrient loading. Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, Lake Erie, and Lake Ontario are ringed with red-colored trouble spots, while Lake Superior stands out as a sea of cool blue health. But looks can be deceiving. The Greatest Lake has issues, too, including algae blooms, aquatic invasive species, and microplastics.

Since a big flood in June 2012, when 8-10 inches of rain fell in Northeastern Minnesota, citizens have been noticing changes to water clarity both north and east of Duluth. After the flood, citizens began reporting algae blooms along its shores for the first time in the history of Lake Superior.

Algae blooms can release toxins, close swimming beaches, diminish the allure for tourists, and lower property values. Kaitlin Reinl, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Minnesota Duluth (UMD), is working with scientists at the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore (APIS) and UMD’s Large Lakes Observatory (LLO) to understand why the algae blooms are happening now.

“The summer of 2018 was huge for algae blooms, based on reports from citizens,” Reinl reported. “We’re wondering if people are just more aware these days, or if historical algae blooms weren’t reported, or if there’s actually been an increase.” To figure out where the algae are coming from, researchers have been collecting water quality data near APIS, and trying to match the observations with algae growth.

They’re also using lab-based experiments to determine if the algae are already in the lake, or if seed populations are being washed into Lake Superior from rivers and inland lakes during floods and then reproducing rapidly.

People have noticed a connection between big floods and big algae blooms, but that might not be the whole story. While scientists look for the answers, Reinl offers suggestions on how folks can help.

“We know that nutrients are connected to growth, so good management of inland waterways can reduce runoff into the lake,” she said.

Minimizing the application of lawn fertilizers, maintaining buffer strips of native vegetation along the shorelines of lakes and rivers, and supporting farmers in erosion control practices are all good ideas. In addition, everyone is asked to report algae blooms anywhere in Lake Superior by calling the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore’s Visitor Center in Bayfield, WI, at (715) 779-3397.

While the algae problem is relatively new, the issue of aquatic invasive species (AIS) is shockingly old. Doug Jensen is the aquatic invasive species program coordinator at the University of Minnesota Sea Grant Program in Duluth. From the moment he started talking, I was astounded at both the scope of the problem and the good news about the control of their spread.

“Since 1830, there have been 187 non-native species introduced into the Great Lakes,” Jensen said. Of those, invasive species include the sea lamprey, rusty crayfish, spiny water-flea, quagga mussel, and purple loosestrife. They interrupt food chains, stress native ecosystems, and damage infrastructure. “But 2006 is like the line of demarcation,” he continued, “The bloody red shrimp is the last new AIS found in the Great Lakes. Since then, we’ve only found one new non-native species of zooplankton, and it isn’t invasive.”

With 100 non-native species, Lake Superior is the least infested of any of the Great Lakes, despite hosting the largest inland port in the nation. This impressive accomplishment is due in large part to a ballast water management program for oceangoing ships started in 1993. When a ship leaves a foreign port, it fills ballast tanks with water to improve stability, balance, and trim. If that water—complete with little swimmers—were discharged into another body of freshwater, it could be a source of invasive species. Since 2004, ships have been mandated to empty and refill their tanks with saltwater in the middle of the ocean. The technique, nicknamed “swish and spit,” ensures that most invaders are discharged, and that salinity levels in the tanks are too high for any remaining freshwater species to survive.

Recreational boaters and anglers can help prevent the spread of aquatic invasive species, too. Signs at public boat landings show visitors how to “Stop Aquatic Hitchhikers.” This national campaign reminds recreational boaters to clean, drain and dry their equipment to prevent the spread of AIS. It’s important for both Lake Superior and for Minnesota’s 11,842 inland lakes. And it’s working. Only seven percent of Minnesota’s waters have AIS.

“If the spread of AIS was inevitable, all of the lakes would be infested by now,” said Jensen.

Education, watercraft inspection and enforcement is largely working to prevent AIS spread. Each year, Minnesota Sea Grant educates more than 10,000 people with AIS prevention messages.

If you stop by the Arrowhead Home and Builders Show—April 3-7 in Duluth—you can hear another of Jensen’s favorite messages. The national Habitatitude campaign educates consumers about the problems caused by releasing exotic animals or plants from aquariums, water gardens, and classrooms into the environment. Through Habitattitude Collaborative Networks, unwanted pets can be auctioned off and rehomed during “surrender events.” Over 500 animals have been rehomed in the past three years. The pets, the owners and the environment all win.

Not all of Lake Superior’s invaders are living, though. Microbeads are tiny pieces of plastic found in facial scrubs, soaps, and toothpastes. They were added as abrasives or exfoliants, but after scientists in New York state discovered how prevalent they’d become in the Great Lakes, they also became headlines. Public outcry led to a federal ban on cosmetic microbeads that went into full effect in July of 2018.

When I talked with Dr. Lorena Rios Mendoza, a Professor of Chemistry at the University of Wisconsin Superior and an international expert on microplastics, she was unimpressed by that accomplishment. She’s been studying microplastics in Lake Superior, and it was sobering to hear her say “We don’t have a solution. We don’t even know the extent of the problem.”

Plastics are everywhere. There are over 5,000 types of plastics that haven’t been banned. Any plastic item of any size can be broken down by ultra violet light into microplastics that are just as bad as those microbeads. Discarded contact lenses, the clear windows in envelopes, and plastic bags are a few common sources.

But plastics are inert, right? Wrong. Many environmental toxins, like flame retardants, pesticides, and other “persistent organic pollutants” are hydrophobic. They don’t bond readily to water molecules, but they are adsorbed easily by the plastics. This can concentrate toxins that might otherwise have settled out into the sediments and stayed there.

Microplastics are a bigger issue in Lake Superior than are chunks of trash, because the little bits look like food to a fish. When a perch eats microplastics, it’s also ingesting carcinogens, mutagenics, and endocrine disrupters. What happens to them, and what happens to us at a fish fry, are questions Rios is trying to answer.

“Plastic is everywhere. We are breathing plastic,” explained Rios. Scientists have found microplastics in tap water, bottled water, and beer. We release plastic fibers from our clothes when we do laundry. Wastewater treatment plants concentrate microplastics in their effluent, and then there’s the garbage.

“When we say reduce, reuse, recycle, we need to add refuse!” advised Rios. She stopped eating at a favorite restaurant because they gave her a plastic drinking straw automatically, without asking. She refuses to take a bag with her sandwich when she goes out to lunch, and she tries to use plastic alternatives like cotton and glass. “I know it is painful,” she admitted, “but we must put pressure on industry to find better ways. We just have one planet. Use it, but don’t abuse it.”

These issues are as big as the lake itself. But the surrounding communities’ connections are also deep. “Lake Superior excites such a strong sense of place in people that I hope this can be our superpower,” said Deanna Erickson, education coordinator at the Lake Superior National Estuarine Research Reserve.