When the Minnesota Legislature adjourns the session, the statewide walleye bag limit may be reduced from six to four fish. The lower bag limit was called for by some anglers who are concerned walleyes are being overharvested. Some fisheries biologists, on the other hand, say there is no biological evidence overharvest occurs. What can’t be argued is that walleyes and other game fish face increasingly intense fishing pressure, winter and summer, from anglers armed with sophisticated boats and winter wheelhouses, fish-finding electronics and GPS, and up-to-the-minute fishing reports from social media. From that perspective, reducing the limit may be justified.

Reducing bag limits and encouraging anglers to practice catch and release are pillars of modern fisheries management. We’ve seen special regulations intended to prevent overharvest and improve the average size and abundance of Minnesota northern pike, sunfish, crappies, lake trout, muskies and more. This conservative approach to fisheries management suggests that even in the Land of 10,000 Lakes, our fisheries are a heavily utilized resource. So why do agencies like the Minnesota DNR, the tackle industry and angling advocacy groups tell us that we desperately need more anglers to prevent fishing from slowly withering away?

R3—recruit, retain and reactivate—has become the mantra for those within the angling and hunting community that are convinced more is better. They believe fishing and hunting are falling by the wayside in our fast-paced, urbanized world. They point to population demographics, where baby boomers are aging out of active lifestyles and urban dwellers may not have opportunities to go fishing or hunting. They also point to participation rates based on license sales, where activities such as duck hunting have declined in recent decades. Since license sales are the primary funding for state fish and wildlife agencies, maintaining or increasing sales is a matter of self-preservation.

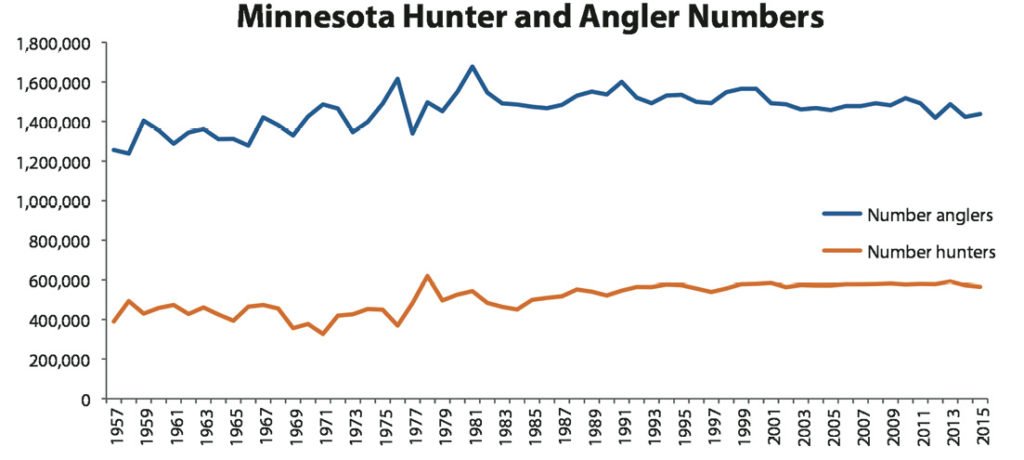

Another statistic often cited is the decline in the percentage of the overall population who hunt and fish over the last 60 years. According to the Minnesota DNR’s R3 Toolkit, “During certain years in the 1950s, 1970s and 1980s more than 40 percent of Minnesotans age 16 or older had a fishing license. Today, it’s about 26 percent. Similarly, from the late 1960s to the mid-1980s about 16 percent of Minnesotans age 16 or older purchased a hunting license. Today, it’s about 11 percent.” But there is a little more to the story. Minnesota’s population in 1950 was about 3 million. In 2020 it was 5.7 million. Perhaps it is unrealistic to expect to have nearly twice as many anglers and hunters today.

If we did have twice as many anglers and hunters, where would they go hunting and fishing? In 1957, folks were less mobile than today. A lot of hunting and fishing happened close to home. Good hunting for ducks and pheasants was available near the Twin Cities in places that have since been lost to sprawl. Most of the state’s lakes were relatively undeveloped and offered good fishing. Big pike, bluegills, walleyes and bass were not uncommon. You could keep your catch and not feel guilty. On the flip side, some of today’s popular species were less abundant, or nonexistent. White-tailed deer were primarily found in the northern forest. Muskies were only in waters where they were a native species. There were no wild turkeys.

In 1957, fishing and hunting were much simpler. Most of the equipment and clothing common today simply didn’t exist. You dropped a line over the side to find out how deep the water was and lined up shoreline landmarks to locate fishing hotspots. In the woods, you sat on a stump to wait for a deer to pass bay and then dragged out your kill by hand. When you went fishing or hunting, nearly everyone you encountered was male and white.

Times have changed. I was born in 1959. My father took me fishing and hunting from the time I was a toddler. As a kid, fishing and hunting opportunities were within bicycle distance of home. Many of my peers had similar upbringings. Nowadays, far fewer people grow up that way. Many have little or no opportunity to experience fishing or hunting, even if they have a desire to do so. Should we find ways to provide them with these opportunities? Yes. Should we bank on these outreach efforts to secure the future of fishing and hunting? No.

Little data exists to demonstrate that R3 efforts are successful. Simply put, taking a kid fishing for a day isn’t likely to create an angler, especially if there is no way to go again on their own. If we want to attract new anglers and hunters, we have to provide them with places to go. In most of Minnesota outside of the metro region, those nearby places still exist, but many already see moderate to heavy use. It is fair to say crowding and overuse are real issues in Minnesota’s outdoors. More troubling, we continue to face long term declines in game species ranging from ducks to deer. The bottom line is we need healthy habitat where fish and wildlife thrive in order for fishing and hunting to attract newcomers and retain old hands. The reason we no longer have as many duck hunters as we had in 1957 is because we have far fewer places to go duck hunting and far fewer ducks in the hunting areas that remain. Given that reality, we are unlikely to see new hunters flocking to the marsh.

Some young folks are coming into hunting and fishing on their own. A developing trend is the increased participation by women. The R3 Toolkit notes a steady increase in deer hunting license sales to women, although they remain a small percentage of hunters. Nationally, however, women now comprise about 30 percent of the fly-fishing community. That said, we also need to recognize the obstacles facing folks who want to go fishing or hunting but are not white males, because they are real. Very often, those folks feel neither welcome or safe in the outdoors, or within the fishing and hunting community.

Creating the societal change necessary to attract more diverse anglers and hunters may be beyond the scope of any agency or industry R3 program. That change may be occurring on its own. By all accounts, the pandemic led to overwhelming participation in all outdoor activities and purchases of outdoor gear. Will it continue beyond the pandemic? Who knows? But it seems unlikely that participation in outdoor activities will return to pre-pandemic levels. Which leads us to a new challenge: where will we put all of the people? The answer is the same as it always has been: Habitat. Protect it. Restore it. Acquire more of it. When it comes to sustaining fishing and hunting, it’s a proven recipe for success.