Grand Marais—If you’ve been fortunate enough to travel to eastern Africa and witness the beauty of the geologic features along the “great rift,” you might have seen Mt. Kilimanjaro, Victoria Falls or Lake Victoria. The great rift is a long, linear valley that is an active tectonic boundary attempting to separate Africa into eastern and western halves. North America experienced a similar tectonic history 1 billion years ago; the evidence is the suite of igneous rocks that underlie Lake Superior in a long, linear belt (in the subsurface) to Oklahoma. This feature is known as the Keweenaw “rift” and some of the best exposures of these rocks are in the Keweenaw Peninsula and along Highway 61 from Duluth to Thunder Bay.

Along Highway 61, most of the rocks are igneous and dark in color (basalt, diabase, gabbro). There are a few pink outcrops (rhyolite; Palisade Head) and there’s the beautiful mix of igneous and sedimentary rocks exposed in the cliff face where Cutface Creek enters Lake Superior (a few miles west of Grand Marais). You may have been forced to sit at this location in the summer of 2015 when the bridge was replaced, and you may have noticed the Cutface Creek wayside and the scenic overlook (with a plaque partially describing the geology) across the highway from the outcrop.

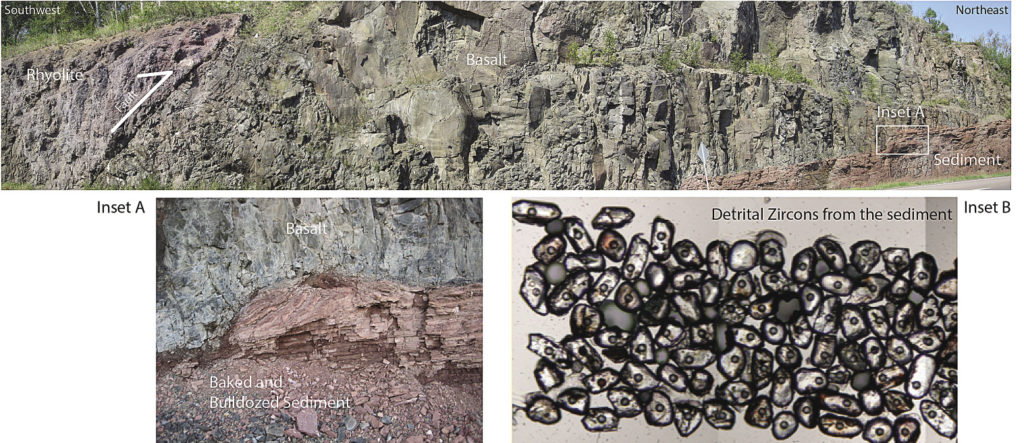

The Cutface outcrop contains three rock types. The lower cliff face is a horizontally layered sedimentary rock. It’s composed of sandstone and siltstone that eroded into a small basin on top of a slightly older igneous basalt flow. This sedimentary rock is red in color because it eroded from nearby basalts, which are very rich in iron.

Later, the sedimentary rocks were buried by a younger basalt flow and the top of the sediments were baked and bulldozed. As the basalt cooled, it cracked and formed regularly-spaced joint partings. Then, the basalt was buried by a rhyolite flow on the west end of the exposure. A fault forced the rhyolite up and over the basalt and red sediment, folding the joints in the basalt along the fault contact. The red sediments contain small amounts of the mineral zircon, eroded from nearby basalts and rhyolites. Zircons contain uranium and lead.

By measuring the ratio of uranium to lead, using a laser to vaporize the crystal in a vacuum (the laser holes are 50 microns in diameter, so the zircon crystals are really small), the age of the sediment can be determined. The zircons in the red sediment are 1 billion years old; consistent with the age of the Keweenaw rift geology.

Unfortunately, these sediments are too old to have any hope of containing fossils, which become common in sediments 500 million years of age or younger.—John P. Craddock