On the North Shore and in the canoe country, the pioneer past is not that far away. Although the region was opened to settlement following the signing of a treaty with the Ojibwe in 1854, the north was so rugged and isolated that pioneers slowly filtered into the region. As a result, some of the pioneer history is within living memory or nearly so.

Jack Blackwell was born and raised in Grand Marais. He went on to have a 40-year career with the U.S. Forest Service. Upon retirement, he spent a month in the Boundary Waters, alone except for the company of his Labrador retriever. He spent that time in a specific place deep within the wilderness where few paddlers travel. It was a place meaningful for him, because it was the heart of the trapping country beloved by his grandfather, Alec Boostrom.

Blackwell was a junior in high school when his father was diagnosed with lung cancer and given six months to live. He died five months later. Because he was devastated by the loss, his mother and grandfather decided that he should take some time off from school. He spent the month of April with his grandfather in a camp on Mesaba Lake, trapping beaver. In the evening, when they processed their pelts, his grandfather told him stories about the past. They were wonderful stories. Blackwell listened and remembered.

In 1914, 14-year-old Alec Boostrom got off the steamer America in the North Shore community of Hovland with his older brother Charlie, Charlie’s wife, Petra and their infant son, Donald. They hired a man with a team of horses to bring them 20 miles inland to McFarland Lake, where Charlie had left two canoes. From there they paddled and portaged westward for two days to reach Moon Lake, where Charlie had previously built a rough cabin. They were home.

They built a second, smaller cabin for Alec to stay in. They put up firewood for the winter and killed a moose for food. Then, as winter approached, they began trapping; first for mink and, when winter arrived, martin and fisher. Alec was initiated into a way of life.

Recently, Blackwell released a book about his grandfather’s life: Boundary Waters Boy, Alec Boostrom’s Pioneer Life in the Canoe Country. In addition to Alec’s stories, Blackwell did extensive background research. The book, which is told in his grandfather’s voice, details a rich history of the Gunflint Trail and the Superior-Quetico canoe country. It provides a unique glimpse into the past of a very special corner of the world.

If the Boostrom name seems familiar, it’s because Charlie and Petra moved to Clearwater Lake off the Gunflint Trail, where they founded Clearwater Lodge. Charlie became a master log cabin builder, constructing a number of private cabins along the Gunflint Trail. His masterpiece was the imposing Clearwater Lodge, which is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

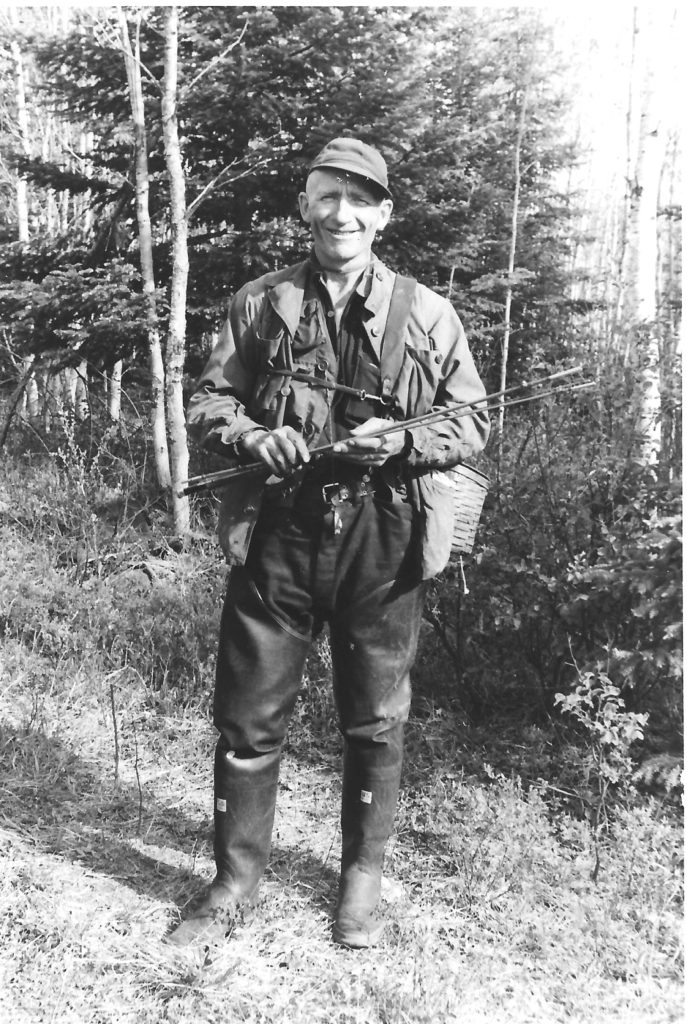

Alec followed a different path, becoming a trapper and wilderness guide. He first found work with the crew that was setting the monuments along the international border with Canada from 1915-18. In winter, the crews surveyed the line across frozen lakes. In the summer they set the monuments. The crew was led by two men, an American and a Canadian, who at times had to decide where the border should be.

Alec began trapping and, with his brother, owned a dog team. It was on a trip from Clearwater to Grand Marais with his dog team that he met the young woman who was to become his wife. Jo Zimmerman’s father Sam, was a white survivor of the Dakota War of 1862. Her mother, Jane Maymaushkowaush Elliot, had lived in Chippewa City, a native community on the outskirts of Grand Marais. This is an important detail in the story, because it drew Alec and his descendants into the native community. As a result, Blackwell approaches some aspects of native life and history with greater detail and sensitivity than other accounts.

An example is the story of Chief Blackstone Two, who live in a native village on Kawa Bay of the Quetico’s Kawnipi Lake. In 1919, the village was beset with an epidemic. Blackstone, one of his wives and the only other healthy man in the village set off for help. They reached the town of Winton, near Ely, where they radioed the Canadian government that the people in the village were dying. There was no reply. Later, the Canadian government forcibly evicted all of the remaining native people living in the Quetico, including some at gunpoint in the middle of winter. Their descendants now live in the village on the Canadian side of Lac la Croix. It was 1991, before the Canadian government issued a formal apology.

For decades, from 1909 to 1952, the area that became the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness was managed as a game refuge by the state of Minnesota in the misguided hope that the wildlife there would prosper and spread out to the rest of the state. For the local people who were trying to eke out a living from the land, the refuge was a farce, especially during the Great Depression. Alec was among the many men who journeyed into the canoe country every spring to trap beaver, which was one of the few ways they could earn cash. He had a couple of small, hidden cabins where he stayed while trapping. Stealth was important, because game wardens were looking for the trappers.

While Alec travelled through the wilderness on snowshoes and with a canoe, he also used the services of a bush pilot named Ernie “Hoot” Hautala from Ely. At the time, low-level flying in the canoe country was still allowed. Alec recounts that flying back to Ely one night after dropping off a trapper, he counted a dozen campfires from the camps of other beaver trappers. In the north at the time, being an outlaw was a way of life.

This brief column barely skims the stories Blackwell compiled in the book ( Boundary Waters Boy, Alec Boostrom’s Pioneer Life in the Canoe Country), including one about windigos—cannibals—on Basswood Lake that may not be found anywhere else. If you know the country and the people who live there, this is an extraordinary read. It is welcome addition to the history of the canoe country.