The following article was written by Dennis Anderson of the Star Tribune. To view the original article, click here.

Wilderness residents come for the adventure, stay for the lifestyle

ON THE GUNFLINT TRAIL – The sun had set behind a distant shoreline when Joe Friedrichs said it was time to go. Our canoes were cast in near-darkness, and ragged silhouettes of pine, spruce and birch rose against a bruised western horizon. A few walleyes swung from our stringer. This was on a recent evening, and we paddled across Swamp Lake, finding our portage and following faint shadows along the rocky 100-rod pathway to our vehicle.

“A good night,” Friedrichs said, hoisting the stringer of fish.

Friedrichs, 32, and his wife, Maggie, 27, are among the most recent residents to stake claims in the big country that brackets the Gunflint Trail.

A 57-mile-long federally designated scenic highway along the northeastern Minnesota border, the “Trail” as it’s called, and the intricate latticework of land and water surrounding it, has long been a magnet for dreamers, schemers, adventure seekers …

And fishermen.

First inhabited by Ojibwe and Cree Indians, followed in the 1700s by French Canadian voyageurs drawn to the beaver-rich region by Europe’s penchant for fur, the Gunflint in the latter 1800s gave way to speculators who broke a lot of pick axes before concluding that Mesabi Range iron ore didn’t extend this far east.

In the century and more since, little by little, the Trail has been transformed from a rutty two-track that extended a few miles inland from Grand Marais to the smooth blacktop that today links that Lake Superior town to the Seagull River more than an hour’s drive distant.

In many ways, the people the Trail ties together today are bound spiritually to those joined by it generations ago, when townlike encampments along the Gunflint attracted railroad men, loggers, trappers, merchants and prostitutes, and when Grand Marais was supplied from Duluth alternately by a muddy North Shore road and by the steamship America.

Married in March in the Twin Cities, Joe and Maggie Friedrichs regularly ply the Gunflint in their compact SUV, primarily the 35-mile stretch that separates Grand Marais from Rockwood Lodge and Canoe Outfitters, where they work waiting on guests and outfitting Boundary Waters canoeists.

“Maggie quit her teaching job in the Twin Cities, and we’ve come up with the intent of establishing a home,” said Friedrichs, a journalist. “The ruggedness, the landscape, the remoteness, the fishing.

“All of it appeals to us. We didn’t just show up one day with a pipe dream and say, ‘Hey, we like it Up North.’ ”

Others did:

An infinitesimal speck in the cosmos, I stood on the shore of Gunflint Lake beneath a great white pine — matriarch of a fast vanishing tribe. And I knew I was home. I was twenty-one. The year was 1927.

Thus was the self-description of the late Justine Kerfoot in her 1986 memoir, “Woman of the Boundary Waters.”

Kerfoot, who died in 2001 at age 94, had been destined by birth for a life of wealth and privilege in Chicago. But the Depression wiped out her parents’ substantial finances, and the family retreated to the tiny Gunflint Lake fishing outpost they had purchased more or less on a whim a few years earlier.

A 1928 graduate of Northwestern University in zoology, chemistry and philosophy, Kerfoot had wanted to become a physician.

Instead, barely into her adult years, she found herself near the end of a very bumpy road, living in a cabin with no indoor plumbing, no electricity, no reliable way to make a living — and loving it.

Her family’s arrival helped mark a demographic shift among Gunflint residents.

Unlike the trappers and miners who earlier had been drawn to the area by its perceived riches, the Kerfoots’ day-to-day lives, and those of others like them, were fueled more by the adventure and lifestyle the Trail offered, than by possible financial reward.

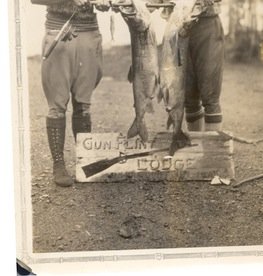

“People who came to the Gunflint at that time, for years afterward and who still come today, were and are part of the same pioneering spirit,” said Bruce Kerfoot, 77, Justine and Bill Kerfoot’s son, who with his wife, Sue, operates the modern iteration of Gunflint Lodge, one of about 15 resort and/or canoe outfitting businesses along the Trail.

Most men — and they were mostly men — who came to fish in the camp’s early days sought the giant lake trout that inhabited Gunflint Lake and other nearby lakes.

Walleyes and smallmouth bass had yet to be introduced to the region, so the trout, along with big northern pike, were anglers’ primary targets.

In fall, when the first snows fell and fishermen stopped coming, survival mode kicked in. People who “wintered in” along the Trail, white or Ojibwe, helped one another, whether during emergencies or to cut huge blocks of lake ice to provide year-round refrigeration in sawdust-insulated “icehouses.”

“Along with my two sisters, I was home-schooled, and when I was a kid — I was born in 1938 — whatever ‘fresh’ food we had, came from our root cellar,” said Bruce Kerfoot, who would later leave the Trail for a time to attend, and graduate from, Cornell University. “For supplies, the only way we got to Grand Marais in winter was to travel 43 miles by dog sled, and we obviously didn’t do that every day.

“What we did do every day was feed our dogs. We kept the team out back of our cabin, and every day we cooked cornmeal mush for them. They were our transportation, and as importantly, they hauled our firewood.”

• • •

Daybreak.

Joe Friedrichs walks into the outfitting cabin at Rockwood Lodge and Canoe Outfitters on the shores of Poplar Lake along the Gunflint Trail.

Inside are tents, packs, sleeping bags, paddles and life jackets — everything needed for a trip into the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, an entry point to which is a short paddle away.

With the previous evening’s walleyes cleaned and cooling on ice, Friedrichs and I, along with a friend, Bob Nasby, will fly fish on this morning for smallmouth bass, paddling from the lodge beneath a blue sky.

Remaining on site at Rockwood will be Maggie, Joe’s wife, and lodge owners Mike and Lin Sherfy.

The Sherfys purchased Rockwood in 2002. One of the Gunflint’s first resorts, Rockwood’s centerpiece lodge is formed from hand-scribed logs joined in the 1920s.

Previously, the Sherfys owned a resort on Cass Lake, near Bemidji, having bought it after Mike retired from a state government job in Ames, Iowa.

“The Gunflint is a whole different ballgame from Cass Lake, where we had sugar-sand beaches and our guests water-skied and tubed, and also fished,” Mike said. “On the Gunflint, our guests come for the wilderness and adventure. They hike, paddle, pick blueberries or drive around looking for moose. They’re self-entertained.”

Not long ago, someone up the Trail shot a nuisance bear, a necessary if somewhat distasteful occasional occurrence.

“Right away, some of us got together to help butcher it, because nothing goes to waste along the Trail — everything is just too difficult to replace,” Mike said.

He added: “That’s the way it is up here. People help each other. When my wife had a stroke a while back, she had to go twice a week to Duluth for rehabilitation. Some of the people who drove her there and back every week, I didn’t even know. They just came to help.”

Casting off from shore, Friedrichs, Nasby and I are intent on helping ourselves — to smallmouth bass.

To that end, paddling a solo canoe, I cast a popper toward quiet, boulder-strewn shorelines, hoping to trigger surface strikes, while, not far away, in a standard-sized canoe, Nasby and Friedrichs similarly send lines airborne.

Nearby, the Gunflint Trail, paved and smooth, in many ways remains unchanged after all these years.

At its beginning is Grand Marais, and at its end, adventure.

SOURCE